Chaos Reigns

Michael Koresky on Singin’ in the Rain

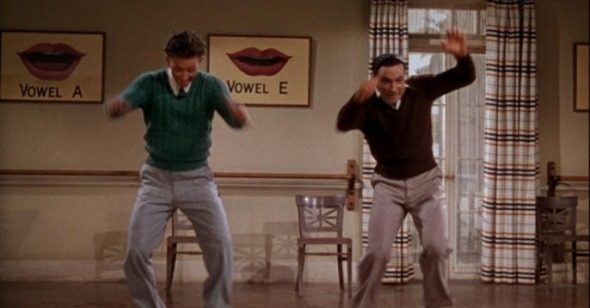

“Moses supposes his toeses are roses, but Moses supposes erroneously.” If you have seen Singin’ in the Rain—as anyone with eyes, ears, and at least a passing interest in the act of smiling should have done by this point—then this odd lyric will summon a host of delirious images. It’s one of many tongue twisters uttered by a stuffy speech instructor hired by a movie studio to whip its newly talking stars into r-rolling shape, and its absurdity inspires dashing Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) and his right-hand piano man Cosmo Brown (Donald O’Connor) to pounce into an impromptu tap dance. What begins as jovial joshing of the teacher, with the two hoofing circles around the bespectacled bookworm and carting him about the room like a sack of limp broccoli, devolves—or ascends—into an expression of chaos: their footwork becomes increasingly aggressive, their gaze to the camera ever more intent. It’s like they’re forcefully dancing across someone’s grave.

Finally, they lay poor teach out across his desk, cover him with rubble grabbed from all over the room—blankets, a chair, a lampshade, a large painting of parted red lips with the words “VOWEL A” underneath. Scattered papers float down like leaves. With wide eyes and diabolical grins, Kelly and O’Connor conclude their number with an elongated “A” sound, referencing the framed picture. There’s an endless outpouring of song and dance in co-directors Stanley Donen and Kelly’s rapturously goofy masterpiece (approximately a full hour of its 105-minute running time is set to music), and many scenes are more famous than this one, but none better captures the anarchy that sets apart Singin’ in the Rain, widely considered the greatest movie musical of all time. And it’s that anarchy—its rule-breaking, illogical, freneticism—that gives the film its energy and personality. For a film so widely beloved, Singin’ in the Rain is truly mischievous, the ultimate expression of a genre that is more about spirit than cause-and-effect narrative relations.

Body is soul in the Hollywood musical; in films of this genre, our ability to move and sing, to swivel our hips and exercise our vibratos, brings us closer to an essential form of existence. Musicals are the imaginary made flesh, and flesh is particularly pliable in Singin’ in the Rain. “Moses Supposes” is a fitting example of this pliability, sending two of its main stars off on an exhilaratingly physical tangent. It’s not a complete non sequitur, though: in treating the speech teacher so negligibly (not unlike that stuffed dummy O’Connor tosses around in “Make ’em Laugh”) and the English language so irreverently (“Sinful Caesar sipped his snifter, seized his knees and sneezed”), antiauthoritarian hepcats Don and Cosmo are expressing their anxieties about the changing values of their medium. It’s thrilling that they do so in such a disorderly manner. Singin’ in the Rain reminds us, in this moment and others, that the upkeep of decorum should never be movies’ number one goal. In a sense, this is the film’s purest scene—the whole film is one, big grin as maniacal as the one plastered on Kelly’s face as the number concludes.

“Moses Supposes” was one of only two songs written for the film; the other was “Make ’em Laugh,” heavily borrowed in phrasing and rhythm from Cole Porter’s “Be a Clown,” which first appeared in Vincente Minnelli’s 1948 Gene Kelly-Judy Garland musical The Pirate. Singin’ in the Rain was initially conceived by Arthur Freed as a vessel for highlighting past songs, a vaudeville trunk of sorts, which he hired songwriters Betty Comden and Adolph Green to help him open (initially skeptical, they would have preferred composing their own new tunes). Such a revue-inspired project was in keeping with the producer’s early, pre-Hollywood years; raised in a Jewish enclave in Charleston, Freed entered show business as a plugger of songs for music publishers. Eventually, Freed would adapt his talents and knowledge to the film industry as it transitioned to sound; among his first major gigs was working in the music department for 1929 best picture winner The Broadway Melody. Two songs from that film—“You Were Meant for Me” and the title track—would end up more than two decades later in Singin’ in the Rain, his own major production about the end of the silent era. By this time, the Freed Unit, his group at MGM, had become short term for lavish, high-quality musicals.

It’s not difficult to see why Singin’ in the Rain remains the pinnacle of these. Few films have maintained such consistent buoyancy throughout, while at the same time clearly requiring a herculean amount of effort. O’Connor’s gravity-defying “Make ’em Laugh” reportedly put the actor—who had a background in the circus—out of commission for weeks, though on-screen he looks like he could pick himself up, dust himself off, and start all over again. Nineteen-year-old Debbie Reynolds appears as carefree as a kitten pawing at a ball of string while flanked by Kelly and O’Connor during that “Good Morning” tap dance, yet according to the actress, her feet were a bloody mess under the ruthless tutelage of her perfectionist choreographer and costar. Kelly’s iconic title number is so spontaneous and winsome one wouldn’t be surprised to learn it was banged out in a few minutes of playful in-between time, yet it took seven days to shoot, while the star was, according to all reports, recovering from the flu and a resultant bronchial condition.

With such behind-the-scenes exhaustions in the back of the mind, one could view Singin’ in the Rain as the ultimate example of the perfection of the Hollywood machine—it moves like clockwork, never lagging, from one gonzo set piece to the next. But machine-tooled it isn’t. Though it takes filmmaking as its subject, it seems to believe that truly great movies require chaos to thrive; thanks to the unknowability of the talkie medium, its actor, producer, and technician characters bear the quality of DIY first-timers. Everything and everyone is given room to surprise, from Reynolds’s not-quite starry-eyed Kathy Selden to Millard Mitchell’s not-quite pompous, studio boss R. F. Simpson to Jean Hagen’s not-quite ditzy starlet Lina Lamont, the closest the film has to a villain. Hagen, peppering her every line with a quirky twist or pronunciation (“I … can … syew!”), never devolves into Judy Holliday–esque dumb blonde pathos; her Lamont comes across as a surpassingly wily manipulator, full of bewitching confidence. That Hagen, in a ticklish twist, provided Lamont’s own dubbed singing voice in The Dancing Cavalier, the film within the film (it’s supposedly provided by Reynolds’ character), only seems to grant Hagen more dominance.

Considering its subject matter and little meta in-jokes, Singin’ in the Rain might have been a terminally self-referential, insider experience. Yet no one could possibly feel excluded from Singin’ in the Rain, as its details ultimately matter less than the feeling it engenders. It’s all about elation. Even the title signifies a feeling more than a literal moment: Don’s rainy jaunt has nothing to do with moving the plot ahead and everything to do with conveying the film’s unspoken philosophy. Kelly isn’t actually smiling through tears in that impossibly ecstatic crane-in on his face (“Come on with the rain, I’ve a smile on my face!”), but the feeling it instills in us is nevertheless something like joy through sadness. The British director Terence Davies said that upon seeing Singin’ in the Rain, his first movie, he was overwhelmed: “I thought this was such happiness, I’ll never know such happiness again—it breaks my heart.” There isn’t a remotely unhappy moment in Donen and Kelly’s film, yet Davies’s quote makes sense. When something looks and feels this right and bright, everything else can’t help but pale in comparison.