Missing Child

by Chris Wisniewski

Viva Pedro: All About My Mother

Pedro Almodovar ends All About My Mother, perhaps his most searing and accomplished work to date, with a dedication—“To Bette Davis, Gena Rowlands, Romy Schneider…To all actresses who have played actresses, to all women who act, to men who act and become women, to all people who want to become mothers. To my mother.” And there, in a nutshell, you have it: in its closing moments, Almodovar announces (though he’s made it clear long before) that All About My Mother is a film about acting, about women, about acting like a woman, about drag, about mothers, about acting like a mother. If this sounds hopelessly convoluted, it bears mentioning that gender, femininity, motherhood, and performance are all deeply connected concepts. But Pedro Almodovar is not Todd Haynes, and you don’t need to have read your Judith Butler to “get” All About My Mother. Mother is far from an academic exercise; rather, it’s stunning and sprawling, a film that captures the giddy spirit of fun that defined much of Almodovar’s early work while cementing a turn towards something more ambitious and meaningful. Above all, All About My Mother is vibrantly alive. It seems to get richer and more daring with each passing frame and with each subsequent viewing.

As it begins, it’s not entirely clear what All About My Mother is about, though in retrospect, Almodovar establishes its central themes with immediate clarity. Manuela (Cecilia Roth) is the single mother of a loving, artistically inclined son, Esteban (Eloy AzorĂn). She is a nurse and former actress, a woman who has done and would do anything to be the mother her son needs, except to share the story of his father with him. They watch All About Eve together on the evening before Esteban’s seventeenth birthday. He decides to write about Manuela, literally penciling the words “all about my mother” directly on to the camera’s lens, and the title credit comes up on the screen, as though Almodovar wishes to collapse, however subtly, the distinction between himself (as author of this All About My Mother) and this young artist (himself authoring a story of the same title).

It’s no surprise, then, that Esteban’s point-of-view dominates the opening minutes of the film, and the loving wonder this boy has for his mother suggests the filmmaker’s personal affections and experience while eliding the autobiographical. For his birthday wish, Esteban asks to watch his mother act the part of a recent widow in an organ transplant procedure training; we watch her as he watches her. Later, he stares at her through a window as she waits for him in front of a theater. At the end of the night, Esteban is hit by a car; as he dies, we see Manuela in a handheld point-of-view shot from his perspective, as though he were the audience to her performed grief.

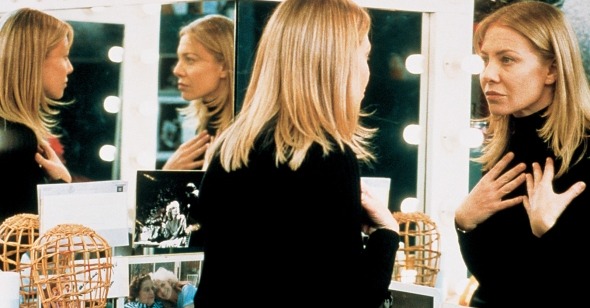

After Esteban’s death, Manuela goes on playing the roles in which she’s cast. She agrees to donate Esteban’s heart in a scene that literally transforms simulacrum into (cinematic) reality, taking the actress from the training and putting her into the role of grieving family member. After Manuela leaves for Barcelona to find Esteban’s father, she assumes the role of surrogate mother to a stage actress (Marisa Paredes), a pregnant nun (Penelope Cruz), and, eventually, the nun’s son Esteban, and at one point, she literally finds herself playing the role of a great theatrical mother, Stella in A Streetcar Named Desire. This being a melodrama and a women’s picture, Manuela surrounds herself with a strong emotional community composed of women who are each, in their own way, also playing a role—the aforementioned stage actress; the pregnant, HIV-positive nun; a prostitute named Agrado (Antonia San Juan), who occupies an ambiguous position between biological womanhood and maleness; Esteban’s father Lola (Toni Canto), who similarly blurs the line between male and female. Role-playing here isn’t a put-on, though; on the contrary, Almodovar seems to believe that for these women, as Agrado declares in the film’s unexpectedly amusing and breathtaking centerpiece, “You are more authentic the more you resemble what you’ve dreamed of being.”

In this film, womanhood, on any terms, implies a kind of acting, whereby a person effectively authors herself through performance. It is in this sense that the use of film melodrama is most effective; for the emotional excess of this film, its profound sense of loss and love, regret and possibility, provides the raw material through which Manuela remakes herself in the face of tragedy. James Crawford, writing about Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown in REVERSE SHOT a few weeks back asks, “Are the inclusion of All About Eve and A Streetcar Named Desire merely a way to lend All About My Mother some cheap gravitas by inducing a frisson of recognition for folks who have heard of the AFI Top 100 (but not watched any of its films), or are they truly imbricated in the plot?” The answer, it seems to me, is decisively the latter: Almodovar turns to these seminal dramas about women, about the roles that women must play, about the price and possibility of performing the role of woman, to foreground the dizzying array of issues he’s taken on here and to underscore the spirit of wicked comedy and overwrought melodrama that make his film such an emotional whirlwind. That the homage is neither overdetermined nor over-intellectualized is actually one of the film’s chief virtues: All About My Mother references its sister texts with quiet sophistication.

In the hands of a lesser artist, a film of such ambition and scope would easily devolve into silly pastiche or scattered mess, but Almodovar has never been more at the top of his game as a filmmaker. His use of anamorphic widescreen here is masterful; his rich color palate is sumptuous to behold; his shot compositions have never been tighter, more controlled, and more precise; and the performances he coaxes out of each of actress—especially Cecilia Roth—are as delicate as they are riveting. With All About My Mother, the Almodovar project, such as it is, achieves a near-perfect visual and thematic unity; it is the pinnacle of an exceptional career.