Tale as Old as Time

By Juan Barquin

Belle

Dir. Mamoru Hosoda, Japan, GKids

Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve’s fairy tale La Belle et la bête has been reinterpreted countless times over multiple centuries. It was initially adapted into its most commonly known version by French author Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont in 1756 and a number of international variants; into films like Jean Cocteau’s 1946 French classic and Walt Disney Pictures’ 1991 animated musical; into television shows, a Philip Glass opera, an Alan Moore screenplay and graphic novel, and even an extended disco number.

That Mamoru Hosoda is the latest filmmaker to take inspiration from the fairy tale should come as no surprise to those familiar with his career, as he has explored the intimate relationships of beauties and beasts from the get-go. Belle retools the fairy tale once again, using its bare bones to explore the way it would play out in a new era where the virtual world is as essential and integrated into our lives as reality itself.

As in Hosoda’s Summer Wars, which took viewers into a digital space called OZ, Belle introduces a new virtual reality known as the U, a digital realm where users can don a new identity to become an avatar of one’s true self. The space connects people around the world and allows a shy high schooler named Suzu to embrace her voice through her new, outgoing persona named Bell (a literal translation of Suzu as well as a play on our dear Belle). Bell transforms Suzu from meek to outgoing, from self-perceived modesty to widely recognized beauty, from just a girl with a provincial life to a bombastic performer with millions of fans and haters alike.

In spite of differences in presentation and perception, Suzu and Bell fundamentally remain the same, as do all celebrities and their performing personae. It’s why Hannah Montana and Miley Cyrus are one, regardless of aesthetic pivots, or, in a less fictional sense, it’s in the way many people used to try to separate Britney Spears the performer from Spears the human being. Hosoda is distinctly interested in what it means to perform, not just on a musical level (though Taisei Iwasaki’s songs written for the film are catchy and gorgeous, whether sung by Kaho Nakamura or Kylie McNeill in the dub) but also in the ways an avatar can change one’s performance of identity depending on both their visage and the space they inhabit. His past works like Digimon: Our War Game and Summer Wars were variations on the same premise, explicitly dealing with the connections we make through virtual spaces.

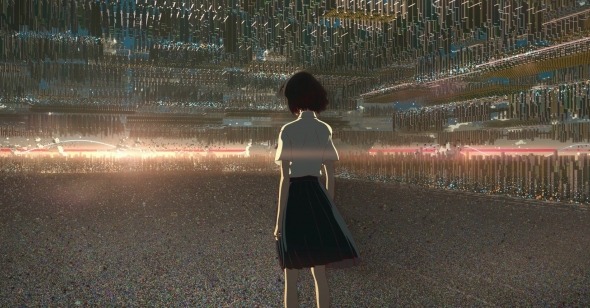

With each film, Hosoda moves animation further from the limitations of reality (a refreshing contrast to the way Disney and Pixar have fixated on hyperrealism within 3D animation in recent years). Though his pet quirks as an animator—notably the outlining of digital bodies in red, as opposed to black for reality—have remained since the start of his career, each film in his oeuvre has taken his experimental blending of 2D and 3D animation a little further. The U is his most ambitious to date, with the wide empty spaces of Our War Game and Summer Wars (only semi-populated by colorful characters) traded in for massive backdrops, intricately designed by Cartoon Saloon (the folks behind Wolfwalkers and Song of the Sea). Where some scenarios seem painted in the same vein as many an anonymous digital cityscape (not far removed from The Matrix), others are distinctly inspired by Disney’s aesthetic choices, down to the character designs themselves, with Bell’s avatar created by Disney animator Jin Kim, playing off his design work for characters in such films as Tangled and Frozen.

The increases in ambition, budget, and technology never detract from Hosoda’s focus on the relationships between the people who exist outside of the U. His narratives remain grounded in the human, no matter how fantastic the plots get (such as 2006’s The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, the tale of a supernatural teen girl which is ultimately about learning from youthful follies). For each scene in the U in Belle, there’s a corresponding one happening in the real world, with Suzu navigating the angst and obstacles that come with being a teenager who's finally discovered a space that makes her somewhat comfortable. As separate as the two might seem, Hosoda knows that an avatar is just a facade. The Dragon, a figure who lives in an isolated castle (the design of which is lifted from Kingdom Hearts’ Hollow Bastion, itself an expansion of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast) and is perceived as violent by the U’s populace, might exist only in the U, but the hunt to discover their identity after the beast ruins one of Belle’s concerts spills into the real world and inspires a global discourse.

Belle is less interested in the mystery of the Dragon’s identity (despite red herrings that highlight the speculation of the app’s consumers) than in understanding what exactly identity means and how we struggle with it on various levels. Their avatar is not a literal manifestation of the self but takes features and morphs them to suit their personality, with Dragon’s doglike visage and cloak patterned to resemble the bruises of a tortured life, as opposed to Belle’s emphasis on beauty and emergence. Much like Beauty and the Beast had the vile Gaston as a villainous authority figure, Belle uses a group of mods hellbent on revealing the Dragon’s identity to explore the way that power and fear can be weaponized against the strange and isolated—or, more pointedly, the queer.

Hosoda’s fixation on internal growth and the malleability of identity is key to his new interpretation of the Beauty and the Beast myth and signals its inherent queerness (much like Howard Ashman’s lyrics for the 1991 film were imbued with the experiences of being a queer man in a suffocatingly anti-gay world, with some numbers distinctly fueled by the anger of the AIDS era and Ashman’s own illness). Characters don avatars that better suit their self-image (from a motherly figure embodied as a bearded muscular man to an innocent child being perceived as a miniature angelic being) and allow them to access this space differently than they would navigate reality. It isn’t so far removed from how various queer and trans people learn to discover themselves within digital spaces by essentially code-switching. To do this, they must often find others who care, people who can perceive what they’re going through and not assume that their identity is a form of malicious lying.

This is precisely how the relationship between the Dragon and Belle plays out, stripping away the romance and instead exploring something closer to a parent-child relationship. Where Wolf Children follows the conflict that comes with raising queer children in a world unprepared for them, and Mirai dove into the deep frustration that comes with having to sacrifice for the ones you love, Belle shows how these digital strangers struggle with their respective realities and come to inadvertently help one another. As much gorgeous animation is thrown at the viewer, the true draw of Belle is how it explores the possibilities for human intimacy on the Internet, despite its ungraspable scale.

His penchant for fantastic narratives has caused many to liken him to Hayao Miyazaki, but Hosoda’s work hews closer to the heightened melodrama of his contemporaries in anime like Makoto Shinkai (Your Name) and Naoko Yamada (A Silent Voice). Hosoda’s tenderness and perpetual optimism are key to why Belle and his other films are as beautifully drawn as they are. In the face of the horrors, abuses, and losses within one’s own reality, Mamoru Hosoda chooses to focus on how people—especially children and young adults—can grow to understand and maybe save themselves and those around them.