Cruising

By Lawrence Garcia

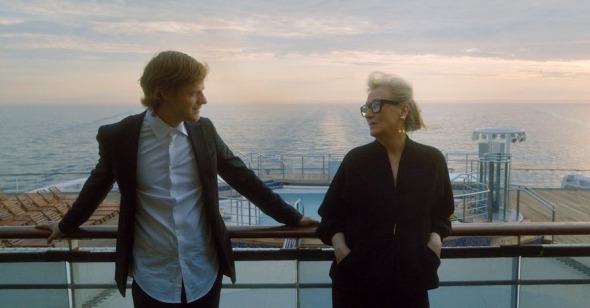

Let Them All Talk

Dir. Steven Soderbergh, U.S., HBO Max

Throughout his career, Steven Soderbergh has displayed both a fascination with the ground-level manifestations of globalization and an ability to leverage the demands of capital into the very style and substance of his creative work. In this, he resembles Olivier Assayas, who has long conceived of his films as Situationist undertakings of a kind, in which a given set of resources—whether it be a Musée d’Orsay commission (Summer Hours) or Maggie Cheung’s stardom (Irma Vep, Clean)—are given narrative weight in order to respond to a particular contemporary moment. And though Soderbergh would probably not describe his own practice in those terms, it nonetheless operates on analogous principles. (In the parlance of High Flying Bird, Assayas and Soderbergh share an interest in playing the “game on top of the game.”) From cinematography (Unsane) to casting (Sasha Grey in The Girlfriend Experience, Gina Carano in Haywire) to distribution (Bubble, Logan Lucky), most any film of Soderbergh’s will exemplify an innovation or resourceful variation of some kind, with his production-phase maneuverings and decisions often mirroring how his characters navigate perilous economies and inhospitable mercenary environments. His latest, Let Them All Talk—shot onboard the trans-Atlantic liner Queen Mary 2, with the ship’s parent Cunard Line likely sold on the prospect of a feature-length plug—is no exception.

Like Assayas’s Non-Fiction (2018), Let Them All Talk uses as its springboard the world of contemporary book publishing, a milieu that allows Soderbergh and screenwriter Deborah Eisenberg to indulge in all sorts of modish observations about the commodification of speech, an author’s responsibility towards her real-life models, technology-driven shifts in consciousness, and other oh-so-topical concerns. Binding all these is that familiar anxiety over (artistic) relevance—though when we first encounter New York–based novelist Alice Hughes (Meryl Streep), she hasn’t yet succumbed to obsolescence. In fact, she’s working on a new manuscript and has just been given the Footling Prize—a prestigious British award that’s not given out annually, as she reminds her literary agent, Rachel (Gemma Chan), and which means enough to her that she travels on the Queen Mary 2 to accept it in person. Still, despite her cultural standing, Hughes isn’t above fretting over her relative worth. When her friends later praise a renowned mystery writer who’s also aboard the ship, Kelvin Krantz (Daniel Algrant), she compares his prose to Styrofoam, not acknowledging the irony that the synthetic material is far more durable than most literary legacies.

The larger occasion for this conversational port of call is a typical dinner on the aforementioned trans-Atlantic voyage, a trip Alice only assents to because she’s averse to flying. Joining her as guests are Susan (Dianne Wiest) and Roberta (Candice Bergen), two old college friends whom she hasn’t seen in decades, and her twenty-something nephew Tyler (Lucas Hedges), who seems to be the only blood relative she hasn’t broken ties with. Also onboard, unbeknownst to Alice, is Rachel, who enlists Tyler to help her find out more about his aunt’s forthcoming manuscript, and whether, perhaps, it’s a sequel to her most beloved book, You Always/You Never. This Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, we soon gather, was based on a youthful affair of Roberta’s—though it’s apparently so thinly fictionalized that a judge granted her nothing when her former husband filed for divorce. Her life having taken a downward turn in the decades since, Roberta is entirely dissatisfied with her current state of affairs (“I hate my life, I loathe my job, I desperately want money”), and still looks to Alice’s novel as the principal cause of her troubles.

This narrative framework is not, in itself, the most exciting of prospects. Indeed, Let Them All Talk bears a logline not so far from the fusty territory of something like Book Club (2018), a movie that’s brought to mind not just by Bergen’s casting (which comes with an awareness of what over-70 actresses tend to be offered in Hollywood), but by the fact that Alice herself forms a pseudo book club, giving each of her guests a copy of a novel—a longstanding literary inspiration of hers—to read during the voyage. (Susan dutifully attempts a few pages before abandoning it for a Kelvin Krantz mystery; Tyler and Roberta don’t even bother cracking it open.) As ever, though, Soderbergh invigorates his material with an exacting eye for detail and an unfailing sense of play. Treating the Queen Mary 2 like an enormous, impossibly expensive film set, and working with a new RED camera, Soderbergh delivers some of the most striking digital cinematography of his career. (The hyaline clarity and lambent glow of, especially, the movie’s exterior shots, make for an interesting contrast to the impasto smears of Jean-Luc Godard’s 2010 Film Socialisme.) Given his career-long admiration of Richard Lester, Soderbergh no doubt drew visual inspiration from the director’s cruise-liner suspense-film Juggernaut (1974), but even beyond this surface similarity, Let Them All Talk also retains that film’s balance of sweeping, large-scale movement and behavioral, character-driven minutiae.

Not naturally given to spectacle, Soderbergh tends to build his films from the ground up, selecting small bits of business and ostensibly minor details from a relentless thrum of complex activity—an approach that applies, here, to his interest in the ship’s vast, interlocking systems, as well as to his characters’ overlapping personal dramas. Minor mysteries and intrigues abound throughout Let Them All Talk, but these are largely secondary to the small-scale pleasure of watching the actors, here given ample room for improvisation, play off each other. Chan and Hedges engage in a one-sided romance chock-full of cringe humor; Bergen and Wiest play their characters’ opposing personalities with the ease of seasoned pros; while Streep hilariously passes off Alice’s inability to connect with all and sundry as a writer’s incessant war with words.

Such struggles of self-expression become a recurring motif across Let Them All Talk. The characters’ exchanges are consistently, amusingly stilted and halting, while the film’s most mellifluous, rhythmic sequences—including a superb embarkation and departure sequence from New York Harbor—are, by contrast, entirely wordless. Likewise, though the film’s scenario creates ample opportunities for rapprochement and renewal, we mostly get a sense of the characters’ competing, irreconcilable agendas, which render them incapable of communicating to each other in any meaningful sense. Bergen’s Roberta, in particular, is openly avaricious, making no attempt to disguise the fact that she wants money from both Alice and any man she might chance to meet on the ship. But as the film unfolds, we gradually come to realize what everyone else stands to gain from their various relationships. By the end, after the scores have been settled, we might even wonder at just how consciously each person was, as it were, playing the game.

What Let Them All Talk thus delineates is an alienated economy of speech to match the setting’s broader, alienated economies of labor—glimpsed when the camera ventures, all-too-briefly, into the ship’s crew areas—where words, like most everything else, are just another market commodity. The film’s seafaring environs recall Hollywood classics such as Tay Garnett’s One Way Passage (1932) and Preston Sturges’s The Lady Eve (1941), where the cruise ship represents adventure, possibility, and transformation—a space where, at least for a time, an enterprising hustler or con might be able to breach boundaries of wealth and class with a dash of sparkling wit or a charming exchange. What Soderbergh understands so acutely, though, is that in our globalized, data-driven present, such havens, like the cons and pros that once populated those films (not to mention his own), are now defunct, with inequities at once recognized and reified to an unprecedented degree. And far from representing an escape from this contemporary state of affairs, the ocean liner is now emblematic of it, acting as a veritable outpost of neoliberal capitalism.

Let Them All Talk registers most forcefully when words drop out, when our attention is drawn to matters verbally unacknowledged and thus tacitly accepted, such as in brief montages that connect dock to cabin, cavernous kitchen to luxury dining room. The looseness of Soderbergh’s method means that plot threads occasionally trail off somewhat arbitrarily, but at its best the film manages to invest its apparent dead ends with resounding rhetorical force. (An ostensibly go-nowhere scene where Alice wanders into a restricted area of the ship, before being escorted away by a crew member, is as close as the film gets to a statement of method.) Unlike Soderbergh’s previous film, The Laundromat (2019), Let Them All Talk operates neither as exposé nor as earnest call to arms. Instead, it’s a film that finds recourse in silence and eloquence in the unsaid, understanding that one often says—and does—more by saying nothing at all.