Book Smart

By Michael Koresky

Reprise

Dir. Joachim Trier, Norway, Miramax

Norwegian Joachim Trier directs his debut feature, Reprise, with such assured kineticism that it’s only a matter of time before Hollywood gets his hands on him and turns him into an anonymous hack. That’s not merely cynicism or a judgment call on Trier’s foregrounded visual flair, which, unlike most other flashy films pitched at the speed of youth, actually contains more true invention than gimmick; it’s just a sad fact of a ravenous industry that subsumes European directors the same way it snatches up the new foreign, art-house ingénue and plunks her down as the latest Bond girl—it only sees the surface sheen. Trier’s considerable talents will be easy to exploit: Reprise courses on the amiable full-tilt thrill of first-time filmmaking. And though the film perhaps tries a mite too hard to ingratiate itself to the viewer (rarely does it leave an emotion not underlined), its rhythms are well matched to its two main characters’ restless pursuits for niche fame and artistic fulfillment.

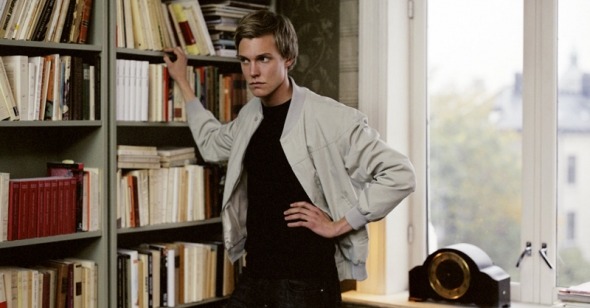

In the rocket-fueled opening montage sequence, twenty-something writers Erik (a lanky and lovely Espen Klouman-Høiner) and Phillip (tightly coiled Anders Danielsen Lie), longtime friends out of school and still living in Oslo, mail their respective manuscripts and imagine, in a series of flash-forwards, their possible futures (in these fictional could-have-beens, as speckled with self-conscious, idealized pain and regret as they are with true success, one of the boys even ends up enacting a heady romance with the suicidal daughter of a French publishing magnate: the dark daydream of spoiled bourgeois boys everywhere?). It’s already obvious that Trier means to indebt himself to the rhythms of French New Wavers such as Truffaut; there’s more than a little “Jules and Jim” in this introductory outpouring of images, accompanied by an omniscient narrator and punctuated by swathes of Georges Delerue’s score from Godard’s Contempt. Despite such lofty intentions, stated bravely upfront, “Reprise” makes fitting use of its references, and leaves the skittish recent New Wave homages by Christophe Honoré, especially Dans Paris, looking like merely studious wannabes. There’s real passion here, and for a while, Trier’s verve is exhilarating.

While it’s always a pleasure to be engaged in the lives of searchingly intelligent people onscreen (such a rarity in American film that the “mumblecore” movement, which by design immersed itself in a paralyzing inarticulacy and featured characters you wouldn’t want to be stuck standing next to at a party, was considered viable entertainment for the book-smart twenty-something crowd), Reprise doesn’t let us quite far enough into Erik and Phillip’s creative worlds. While we’re thankfully deprived of having to watch them go through the process of writing (which is usually overdramatized onscreen), we still never quite get a sense of what’s in their books: this makes the emotional fallout of their divergent paths—Phillip is published instantly, and goes on to a mental collapse; the more stable Erik, cursed with clean-cut looks and lacking his friend’s brooding intensity, has a harder time finding interest—seem more schematic than felt. Their intellectual pursuits also make their lingering friendships with a bunch of crass, misogynist former punk-band mates a bit of a stretch; these dopey side characters are meant to stand in for that which Erik and Phillip need to overcome, but aren’t believable dramatic foils.

How women feature at all into this reportage from the front lines of self-doubting masculinity is one of Trier’s biggest hurdles; and aside from a misguided bit of stylization in which Erik’s girlfriend’s face is mostly left off screen—her character abstracted into wisps of her blonde hair, the back of her head, an elbow in bed—he manages to make his female characters peripheral but not addendum. The most present is Phillip’s long-suffering obsession, Kari (Viktoria Winge, prettily gawky), trying to figure out how to move forward with him once their romance had been forestalled by Phillip’s institutionalization. Phillip and Kari’s tentative reunion is nicely performed and punctuated by elegantly incorporated flashbacks to happier times, but Trier’s film is much better at navigating the uneasy terrain where professionalism and artistry collide, an especially rocky intersection when experienced in your twenties. Subtle jabs at the publishing industry and unspoken games of male one-upmanship add texture to Trier’s debut (which gets quieter and wiser as it goes along); the film’s single best scene illustrates a deflating encounter at a promotional party between Erik and his poet idol, Sten Egil Dahl—brimming with discomfort, the exchange nicely depicts Erik’s awkwardness maintaining that delicate balance of modesty and self-promotion that comes with his newfound territory, and the self-disgust that comes with his realization that he’s just like everyone else.