Text of Light No. 6

Everything Is Now: An Interview with J. Hoberman

By Jordan Cronk

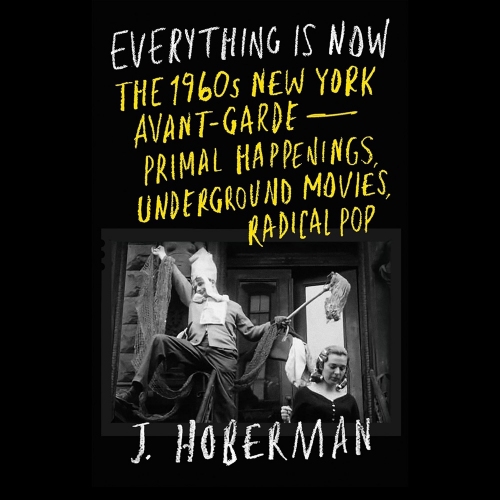

With Everything Is Now: The 1960s New York Avant-Garde—Primal Happenings, Underground Movies, Radical Pop, veteran critic J. Hoberman revisits the scene he cut his teeth on as a young cinephile and arts enthusiast in the years just before becoming a film critic. Beginning in the late 1950s, during the waning days of the Beat Generation, and reaching into the first flowerings of the 1970s midnight movies circuit, the book traverses a wide swath of mediums and movements that, in the author’s telling, coalesced into what we now recognize as the counterculture of the mid-to-late 1960s.

Using reports and advertisements from the era’s alternative newspapers, Hoberman charts the development of various artistic subcultures, which saw underground movies, avant-garde theater, free jazz, folk music, and Pop Art commingling in a downtown arts scene that produced names ranging from Andy Warhol and Yayoi Kusama to Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler to Jack Smith, Ron Rice, and Jonas Mekas—the latter of whom, through his writings for the Village Voice, acts as an unofficial guide through the era’s frequently under-documented happenings. Hoberman, meanwhile, in his role as observer and, eventually, participant in this burgeoning moment (the book ends with the publication of his first review for the Voice, on Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures), provides a unique perspective as a once budding journalist who knows how ephemeral things like dates, addresses, and first-hand accounts truly are—especially in a scene that had no designs on lasting in the cultural consciousness.

In September, I welcomed Hoberman to Los Angeles for the local launch of Everything Is Now and a program on 16mm short films. The night prior, we met up to discuss the personal nature of the book, its focus on New York City as a protagonist, its relationship to his earlier books The Dream Life and Midnight Movies (co-authored by Jonathan Rosenbaum), and some of the discoveries he made while researching and writing.

Reverse Shot: I thought we could start with the last sentence of the book, where you write that you “consider the book a memoir, although not mine.” I think that’s an accurate description, but at the same time the book struck me as maybe your most personal to date, in the sense that it deals with your early years as a cinephile and fan before you began writing criticism.

J. Hoberman: It’s very personal. And not just because it deals with things which, if I didn't experience, I was to some degree aware of but also because it has a lot to do with my personal formation. After doing the Cold War trilogy [The Dream Life, Make My Day, and An Army of Phantoms], I felt like I had had it with Hollywood movies and commercial films in general. That’s not really where I started; that’s not what got me interested in cinema. So I wanted to go back to that. And then the other thing is that it’s very much about journalism. Not just the Voice, although the Voice was crucial, but the other underground papers and the alternative press in general. That’s one reason I wanted to take a journalistic approach to this history, too.

RS: I’m wondering if you can talk about the chronology of the book. It’s about the ’60s, but as far as cinema goes, it begins with Shadows (1959) and Pull My Daisy (1959) and ends with El Topo (1970) and your first film review in the Voice in 1972. How did you come to these specific bookends?

JH: It just made sense to me. You could say it’s the long ’60s. It would have been more arbitrary to start with 1960 and end in 1970. This just made much more sense, given that I was looking for anticipatory work or things that happened beginning in late 1958 or so. A lot of it was instinctual, although once I began, thinking about that particular time frame, what was going on in 1958 and 1959, a lot of it just came together. In terms of ending it where I did, I knew that I would end by citing the first piece that I did for the Voice. As I say in the book, from that point on I was to some degree a participant in this world. I wouldn’t make great claims for that, but it was different than being an observer. So it seemed like a good point to end. And I also think that the moment was winding down then, too. So it worked out. To me the chronology seemed kind of natural—it didn’t seem forced.

RS: It also segues nicely into what you cover in Midnight Movies. You could read the books back to back and probably come away with a pretty good history of ’60s and ’70s underground cinema.

JH: That’s true. It’s certainly related to Midnight Movies. When Jonathan and I wrote that book, we were separately approached by the publisher, Harper & Row. We both were interested, so the guy said, “Well, why don’t you just collaborate?” I was the third-, maybe second-string critic at the Voice at that point, and he was at the SoHo Weekly News. And we kind of knew each other. But we brought different basic interests to it. Jonathan was really, really fascinated by the whole Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) thing. And he had his own take on it, having been the son of a movie exhibitor. I was much more interested, initially, in being able to write about this period in underground movies, which I already loved. So that was a great pleasure for me to write about. I think this book is a return to that.

RS: You guys wrote that book fairly close to the time period that it covers. Do you think you needed the time and perspective to properly assess the era you cover in Everything Is Now? I’m guessing there’s no way you could have written this book in the ’70s.

JH: No. It took about 50 years for me to come back to the material.

RS: Do you think that the era also needed the time and space to formulate in the greater cinematic consciousness?

JH: Maybe. This is another reason one could say that it’s like a memoir, but not mine. When I first started talking about this book, nobody was all that excited or encouraging. I don’t think that people necessarily thought that it had to be written. It was a strong, internal thing. It’s so much work to write a book, that if it’s not something that you really want to do—at least for me, I can't do it. Especially since, in my experience, there’s never any money to be made. It’s like you’re subsidizing; if you worked it out on an hourly basis, it would be ridiculous. So it has to be something that you really want to do. And I really did want to do the Cold War books. That was very important for me then. But this was coming from me. This was not like Midnight Movies, which was suggested by a publisher.

RS: That begs the question, then: why now?

JH: I had a conversation some years ago with Richard Goldstein, a Voice writer who was kind of like my rabbi at the paper. He was my first editor there. He brought me in, and we stayed in touch. He said, “You know, at a certain point, you just have to figure out what you still have in you to do.” So that played into it. I figured that if I was gonna do this, I had to do it now. I wasn't gonna wait. Once I got into it, and once I figured out how to do it, I was very absorbed. Because this was not something which came to me immediately. For these kinds of generational portraits, you typically take ten or twelve people and you write about them. There’s this book called Ninth Street Women [by Mary Gabriel], which is about female abstract expression painters. It’s a terrific book, very well researched. But it’s focused just on these specific individuals. I wanted to do something that was broader. And I didn’t, in the end, want to focus on individuals that much. To me, the city is the protagonist. One could say that the two midcentury or late 20th century American artists who are the most written about are Andy Warhol and Bob Dylan. So, obviously, they’re there. But I didn’t want the book to be about them, as much as I enjoyed writing the chapter where they both come in contact with each other—that was a lot of fun. But I wanted to include many more people, including some who are not known at all, and others, like Yayoi Kusama, who’s famous now, but she had this whole other existence when she was merely notorious. So I came to this idea of working out a collective portrait. Then what I would start with often was not the individual so much as works, individual works, and play around with that. Once I got into it, it was very organic.

RS: I was thinking about the book in relation to the Cold War trilogy and the way each of them covers a specific decade. But where the trilogy takes a macro, or national, look at each era, Everything Is Now takes a localized look. How did your approach differ knowing that you were going to present a more on-the-ground view of this period?

JH: When I was writing The Dream Life, the first book in the Found Illusions trilogy, I felt a little guilty about not including all this other stuff, which seemed just as significant to me as the commercial films I write about. That was another thing that made me want to get back to this era at some point. In that sense the book is a kind of parallel history to The Dream Life. It covers exactly the same period. And actually, there are some things, like Norman Mailer’s film [Maidstone, 1970], which show up in both.

In both cases, I needed to have a very good chronology before I could write—I’m a real stickler for that. I spent a long time working on and refining the chronology. Maybe that was a way to keep from writing, but it was really important to have that. It’s hard for me to remember if I wrote The Dream Life chronologically or not, but this book I definitely did not write chronologically. I was interested in establishing a chronology, and it was fairly detailed, but I would work on this part, and then that part, and then I would get other ideas. In that way, it was maybe more creative, because I was discovering a lot of things as I was working on the book. And the crazy thing is, I even discovered a lot of things after the book came out, both from the reviews, and from reading it as a book. So that was a great feeling. It’s not like it was automatic writing, but I was following certain impulses without necessarily intellectualizing them. So it found its own logic while I was working on it. I also didn’t take a great distance from the material. I focused on the reception of the work, which is true of the Cold War books, too.

RS: I’m curious about the transition between subcultures and the counterculture you establish about halfway through the book. Maybe the designations are obvious, but I had never really thought about them in such a clear-cut way. When did that idea come to you?

JH: It was as I was beginning to work on the end of the book and the overall linearity. I saw that there was a certain progression. I also wanted to split the book in two. It’s funny, there’s an error in the finished book, which will be corrected—they’re doing another printing, which is nice. I had it written as “subcultures,” plural, and “counterculture,” singular. And it is that way when it first appears in the book, but then they turned it into “countercultures,” plural, which is all wrong, because one of the through lines is that through these various individuals there was a certain coalescing of energies that happened later in the period, which also lost its momentum for various reasons. So, in a way, that counterculture is a historical formation. At the beginning, you just have different groups or individuals pursuing their own paths, even though there is a lot of overlap—connections which I really enjoyed finding between the various people and movements.

RS: How did you decide on the pivot point?

JH: Well, at a certain point I had to go back. It was not easy to keep the straight chronology, because there's all this simultaneity. There’s a chapter in which I go back to a certain moment in late 1965 and begin to discuss some of these artists coming together, like the Park Place Group, which is something that I discovered while working on the book. And then I wanted to talk about The Sky Socialist (1965), which is this break in Ken Jacobs’s work, and what was going on in Lower Manhattan. So, I had to begin again, and from there I was able to push those things along into what, by the end of the chapter, seem to me to be less subcultural and more countercultural.

RS: Can you tell me a little about researching the various alternative press papers and the interviews you conducted with some of the writers from the era?

JH: Well, I went through every issue of the Voice from late ’58 to early ’72—just taking notes. Some of it was online, but not all of it. And even when it was online, it was not always complete. So, I had the luxury of going through some of it online, but then the rest of it I found on microfilm. Same thing with the East Village Other and Rat and the New York Free Press and some of the other journals. That was done on microfilm at the Columbia Library. So, it was me hitting the microfilm—that’s what historians do, the ones that I know. You have to go to primary source material, and, in my case, these journals were the primary source. What’s astonishing is that if something’s not online, it’s like it doesn’t exist. It’s really sort of shocking. So, it was fun, but it was kind of arduous at the same time.

I used those to create a chronology, and I discovered things along the way. I knew about the East Village Other, and I knew about Rat, and I read them casually. I was not particularly impressed with the writing. I liked the underground cartoons. But coming back to them years later, there were certain writers I found extremely interesting, and I put them in the book. Unfortunately, a lot of them are gone. I did a certain amount of interviewing, and there were some people who were alive whom I didn’t feel like interviewing because they had already done memoirs. Ed Sanders, for example, wrote a very detailed memoir, which is really great. But I learned that once somebody does that, you’re not going to get them to say anything new. You really would have to throw them a curveball, and when somebody’s, like, 80 years old, they’re not interested in that. Also, what people say is intensely subjective. It has to be understood that way. But there were certain writers I really would have wanted to talk to. There was a woman, Lita Eliscu—I certainly remember her byline; her name stuck in my mind. Who is she? She’s got this Romanian name. I didn’t care much for her writing, or her sensibility. But she was there for a lot of things. She was thinking about it; she was writing every week. I would have loved to have spoken to her. But someone like Richard Goldstein, whom I knew very well—he invented rock criticism, but he wrote his memoirs, too. So that’s what he remembers. I would ask him about things, but it was very frustrating.

RS: Did the papers also help you with the details regarding the geography and the addresses of the venues that you include in the book?

JH: To some degree. I was very interested in the ads and the listings in the Voice. It’s funny, though: people have all kinds of websites that they maintain that include this kind of information. There’s this one called Warhol Stars, which is incredibly detailed in culling together everything that was written about Warhol and the Factory. Dylan also, and the Velvet Underground. And then there are people who just get involved in venues, the history of different clubs. A lot of that stuff I was able to find online. I would say they’re like fan sites, but I don’t mean that in a derogatory sense. It’s like Wikipedia or something. They’re like these amateur historians. It’s great what they do. There are people who are interested in every single movie theater that ever existed in Manhattan. I’m sure that’s true here [in Los Angeles], too. They’re just obsessively documenting these things. So, I found a lot of the addresses through those, as well as from the ads.

RS: Can you talk about wanting to have the book double as a sort of a geographical history?

JH: I wanted that very much. And people do comment on it. I was at first worried that Verso, the publisher, would find it too nerdy or too obsessive. But I had a great experience with them. I have no complaints and only good things to say about that. Part of it was that they left me alone until the very end, and then the people who were working on the editing got very interested in the book. Which was great, because they were much younger than me—most of them were probably around 30.

But it was important to me because I wanted to be able to map this in my mind. Whenever you’re in Paris, you’ll noticed that there are all these plaques. You walk by a building, and it says, Charles Baudelaire Lived Here; Victor Hugo Lived Here. They’re very aware of the historic aspect of the city. New York is nothing like that. Things disappear and nobody pays any attention. I’ve always thought that in SoHo they should have put up little plaques like they do in Paris—Don Judd Lived Here; Yoko Ono Lived Here. So, I did that, then, and I’m glad that people appreciate it. I wasn’t able to include a map, but that’s okay. People can figure it out if they want. You could make a walking tour if you want to, though probably none of the stuff is there anymore. It's part of the appeal of urban life—the density and the specificity of the place.

RS: At what point did you realize that Jonas Mekas was going to be sort of a guide through the book? He’s such a presence throughout.

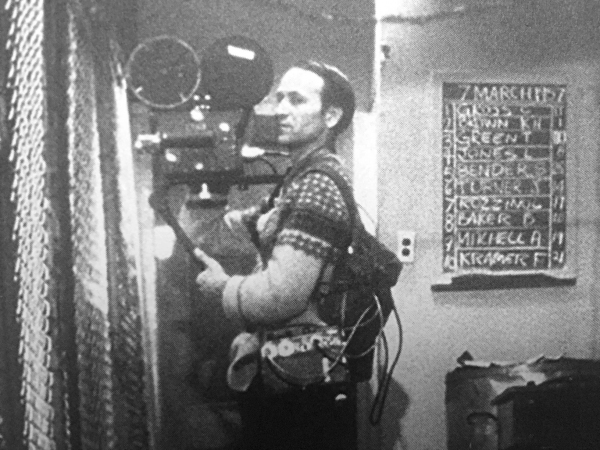

JH: I only truly realized it when I worked on the index. He dwarfs anybody else. Warhol and Dylan have maybe half as many mentions. But I always knew he was going to be important. Even when I was thinking about it as a twelve-artist story, he was always going to be one of them. And it wasn't so much because of his films. When I was young, I was very impressed with Walden (1968). And I also liked very much Lost, Lost, Lost (1976). But other than that, he was not my favorite filmmaker. I did write something in the book about Guns of the Trees (1961), which is maybe his worst movie, just because it fascinated me—like, he’s trying to do something, and he can’t do it. Failed ambition is something I have complicated feelings about. I respect the effort, but it’s like—I don’t want to patronize it, but there’s no success like failure, you know?

So, it wasn’t necessarily Jonas as a filmmaker, although I did come to think that The Brig (1964) was really a major movie that has been insufficiently recognized. And so, I gave that a lot of space. But certainly, it was Jonas as the writer. I mean, he’s the guy. I had gotten a look at his diaries before they were published. This was at Anthology Film Archives, when it still operated a library, which had files of really interesting things, and one of them was Jonas’s unpublished diaries. I was able to track the making of Guns of the Trees, which is fascinating. And then there was Jonas as an organizer. He’s an enigmatic guy. But I think that he’s a good central figure, because he's a little older; he’s of a generation of artists who were really scarred by the war.

I always found Jonas kind of difficult. I admired him, but I also was put off by a lot of things. But if you think about it, he comes to New York; the rents are cheap enough; he can scrimp and save and get a camera; he’s inventing this whole thing in the city. And he’s so aware that the city is making this possible. I find that very compelling. You could compare him to Europeans like André Breton, but that’s like bourgeois posing by comparison. Breton comes from a doctor’s family in the provinces, and he comes to Paris and sets up this whole thing. But Jonas comes out of nowhere. He’s living in poverty with his brother and makes all this happen. I saw him as a kind of local hero. The same thing is true of Warhol and Dylan. They’re provincial guys who show up in New York and kind of conquer the city. And that’s part of it, how the city, in its indifference, could make possible these tremendous forms of ambition. I would say that Kusama is another one, but she flames out and has to leave, and then she checks herself into a mental hospital in Tokyo and becomes the most famous artist in the world.

Jonas Mekas on the set of The Brig

RS: As a kid, were you also interested in the other scenes covered in the book: music, theater, Pop Art, etc?

JH: I liked Pop Art when I was a kid. I was interested in painting. I got more interested in art when I was in college in the late ’60s. A friend of mine had a subscription to Artforum. His parents gave it to him. And he just handed me all these Artforums like, here! What was so significant to me about that was realizing that Manny Farber wrote for Artforum. But I enjoyed the whole thing—Michael Snow, people like that. It helped me get interested in the arts.

I was kind of following theater at the time, but it’s rare that I actually saw something that I write about in the book. Robert Wilson’s Life and Times of Sigmund Freud—I saw that. Hermann Nitsch—I was there for one of his things. But for the theater history I was really relying on descriptions.

As for music: I was into music the way all young people are into it. I never played an instrument. I can’t read music. I liked certain stuff and could never have intellectualized it. Dylan was a special case, but I was sort of a folky. I liked rock ’n’ roll. And I even like some jazz. But this was something that I had never written about. So I’m glad if it seems like I had some expertise, because I really had to learn that for the book. And I’ve seen how people write about jazz. I’m writing about it in very elementary terms. I’m pretty ignorant about music. But what I can do is understand why certain stuff was radical or revolutionary. You don’t have to understand music to see that Ornette Coleman was doing this completely other thing, or that Albert Ayler was great. In fact, I bought a number of those Impulse and ESP LPs during that period, and I held on to them. There’s lots of other things that would be very interesting for me to have now—things related to rock musicians that got lost or that I lent out or whatever. But music is also something that became pretty central the more I worked on this.

RS: Do you have a memory of your first exposure to any of these scenes? A first underground movie or concert or play?

JH: There are a few things that I put in the footnotes. I think most of those deal with various Dylan concerts. For example, I would read these descriptions of the Dylan concert at Forest Hills, about how people were bullying and this, that, and the other thing. Well, I have a different memory of it. Sure, I was 16, but I figured that that should go in the book. And there are other things that are mysterious to me. Like, I have no memory of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. It’s odd, because I certainly knew who Warhol was; I had actually seen some of his movies. I was aware of him as a filmmaker. I’m pretty sure I might have known who Edie Sedgwick was. I was sometimes going to movies on St. Mark’s Place. It wasn’t like it was alien territory. It was a pain in the neck to get there because I lived in Queens, but I certainly was not unaware of it. But I had no memory of the EPI; no memory of having to bamboozle my parents if I was going to go out late or something like that. But the USCO exhibit, the Psychedelic Arts Show, at the Riverside Museum, that I remember. And it was virtually at the same moment. So that’s mysterious to me. When trying to write about these events, you’re really just dependent on what journalists wrote. So I figured that, to the degree that I can contribute some recollection, I would include my memories of certain events, even if I can’t go into details. It’s the same thing with the Robert Wilson play. I can’t really comment on it. What did I think? It seemed far out, I don’t know. [Laughs]

One thing I do remember is developing an aversion to El Topo, which I don’t think I was able to really express in Midnight Movies. I got that chapter kind of by default. Jonathan hated the movie, and he came up with the idea to include that really hilarious quote from George Orwell about Salvador DalĂ. But I didn’t like the movie either, and I had actually gone to see it twice because I didn’t trust my opinion of it. Everybody was making such a big deal about it. So it was a complete surreal coincidence to encounter Jodorowsky in New York and then in Mexico. I couldn’t not put that story in the book. But it’s very fitting that it comes at the very end.

RS: It’s been a long time since I’ve read Midnight Movies, but I don’t remember it coming off like you didn’t like El Topo. If anything, it probably made me want to see it more.

JH: Yeah, I certainly didn’t put people off. The thing with Midnight Movies was that, even though Jonathan and I had opinions, and certainly liked some things better than others, we weren’t judging so much. We were trying to account for this phenomenon, which I thought—and I guess he agreed—was like the continuation of the counterculture by other means. So that’s what we were interested in. He didn't like John Waters either. That’s how I ended up doing that chapter. And I had mixed feelings about Waters, although I came to appreciate him while I was writing that chapter. You might think that he would have been figured in this book, but he doesn’t, really. He comes in as a witness, but just as an NYU student. If Multiple Maniacs (1970) had shown at the Elgin instead of El Topo, that would have been in the book. But he couldn't get it shown in New York. It had its initial life in San Francisco as part of the whole other thing that was going on there.

RS: You mentioned Guns of the Trees earlier, but I’m sure there are a number of films you write about in the book that you don’t particularly like. You don’t offer qualitative judgments on say, No President (1967) or most of the Warhol films outside of Chelsea Girls (1966).

JH: I think that No President is a problematic film. But what I was getting at there was, again, that it has to be considered a failure—as was Normal Love (1963), which is a much more enjoyable film—because he wasn’t able to complete them. They don't exist in any final form. I just think that he was traumatized. But this is something that I speculate on in the book: What happened to Jack Smith? How was he able to do this thing [Flaming Creatures], which is so radical, that made such an uproar, that had such an influence on so many people and, to my mind, is so enjoyable? And then to be so confounded by expectations and your own neuroses that you can’t follow it up?

RS: Flaming Creatures is the other major through line in the book.

JH: To a large degree, underground movies are the heart of the book, though they’re by no means the sole subject. When I was promoting the book in New York, I was in touch with the guys at Anthology, and they were very helpful to me—John Klacsmann and Andy Lambert when he was there. They were very excited when the book came out, so I said I would program a bunch of screenings there. But I didn’t want to do screenings anywhere else, because I didn't want it to get pegged as a film book. But there’s a special connection to Anthology, I felt. And that series was a lot of fun; it was very well attended. People were really excited. I was very happy to do that, but I didn't want it just to appear as a film book, even though movies are so central to it.

RS: How did you find the right balance between cinema and the other arts you wanted to cover?

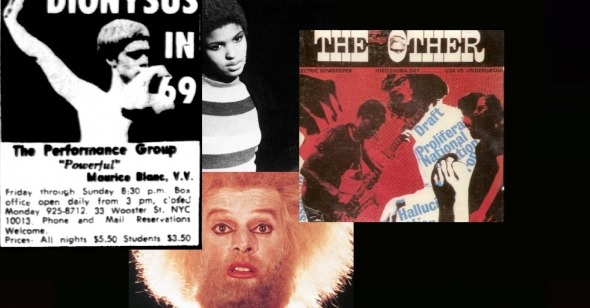

JH: I pretty much talked about everything that I wanted to, but I probably could have emphasized some things more. I wanted to get it all in there. As I was working on the book, I began to realize certain things were much more significant than I had thought. For example, theater: I was there the second time the Living Theater came in. I saw a number of their performances. But I didn’t feel like my account would have added anything to the other stuff that’s out there. These shows were so well attended and so discussed. It’s not like I had anything special to say about it, so I didn’t include that. But something like Dionysus in 69—I vaguely remember being aware of that, but it sounded like some kind of hippie thing. So I never went to see it. And then while working on the book, I realized that this was a very significant event. So that took on more weight than it would have when I first began planning the book.

RS: One thing I discovered through the book is the filmmaker Jerry Jofen, who you mention in a footnote. I tried to do some research on him, but there’s very little information available online. And he’s only mentioned briefly in P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Cinema. What can you tell me about him?

JH: Well, everything that I know, I put in in the book. [Laughs] But there again, it’s very dependent on the writing. I don't know if you're familiar with Steve Dwoskin’s Film Is? The best thing about that book is this incredible introduction by Joan Adler, who was on the scene during the summer of ’63. She writes about these people and it's like a Rosetta Stone, because she doesn’t always tell you what people’s last names are. You have to figure it out. Her take on the scene is fascinating. But Jofen turns up in that. I knew about him because I knew Ken Jacobs very well. And I knew that this was somebody Ken hated. [Laughs] So I thought that was interesting. Anthology actually did a Jerry Jofen screening. When I started writing at the Voice, he had returned to religion, and had done some films on Jewish rituals, which were shown at the Whitney and I wrote about them. So I did know about those, but that’s not the stuff that seemed so interesting to me. P. Adams had written maybe 500 words describing his loft, which I quote in the book. Otherwise, there isn’t much. It’s an example of how something can be lost so easily. And in a way it is, because who knows what happened to these movies?

RS: Are there people you discovered while working on the book?

JH: I wasn’t aware of Boris Lurie until I went to this really great show at the NYU Art Gallery sometime before the pandemic. His work figured in there, along with Aldo Tambellini, whom I knew because of the Gate Theatre, though I didn't have that much sense of him as an artist. On the music side, I had never heard of Bill Dixon. And I was unaware of this journal that Amiri Baraka put out called The Cricket. So, I was finding things out and configuring them. There’s this director, Jerry Benjamin, whom I had never heard of. He was an avant-garde theater person. He worked with Warhol. He directed Taylor Mead and certain LeRoi Jones plays, as well as something that sounds like a fascinating precursor of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. But this guy vanished. I spoke to one actress who had worked with him; she’s actually the one who put me onto him. She said she doesn’t know what happened to him. She went to Europe, and he went to Los Angeles, and maybe there was a drug thing. Maybe there's some trace of him here in L.A., I don't know. But there were all sorts of people who showed up and disappeared. There’s another guy, Richard O. Tyler, who was kind of a mentor for Claes Oldenburg; he founded a religion. It was a very rich period; it was full of people who had great ideas and just added to the general milieu. The geniuses, like Dylan and Warhol, they were like sponges. They were absorbing all this stuff that was in the air. And you can’t fault them for that, because once an idea is out there, it’s out there. A lot of the people they got their ideas from were never heard from again.

RS: Other than The Brig, were there other films or albums that you revisited and changed your opinion about while working on the book?

JH: I don’t know if it was while I was writing the book or just before, but I’ve really changed my estimation of [Michael Snow’s] New York Eye and Ear Control (1964). I really think that’s a major, major film. It’s not like Snow just began with Wavelength (1967). He had done something very substantial before that. I had even bought the Albert Ayler soundtrack LP, but I think that was after I had seen Wavelength, when I was studying with Ken.

RS: To go back to something you said earlier: one of the things I found most inspiring about the book, particularly in light of the current state of journalism, is how it reinforces the necessity of writing and criticism.

JH: Right. I mean, so much of this work was performative. Yeah, the films exist, although not always and not always in such great form. But video didn’t come along until later; people were not making video recordings of happenings or theater pieces. Music is performative. A lot of the poetry exists on the page, but it’s really the readings that were so significant. So this material only existed as people wrote about it—either in their memoirs, or I think more immediately, when it was happening. In that way, the book is a tribute to journalism, and a kind of memorial to what remains of this stuff: the descriptions and the occasional film record.

I think that criticism is necessary. There’s got to be some kind of feedback. Artists may have a love-hate relationship with criticism, but everybody likes a good review. It’s human nature. I know this from experience, that you can give something a really great review and have one reservation, and the artist—it’s like the Princess and the Pea, they’ll obsess over that one thing. But if people don't respond to the work, what is it then? Sure, there are things that are discovered posthumously, like Vivian Maier, the photographer. You can’t say that it was criticism that brought her work to the fore, but it certainly helped. And for living artists it’s crucial. If people have a profound response to something, then it’s natural to want to write about it. Listen, I made a living doing it for so many years, so that’s a whole other thing. But what a great way to make a living. I was very lucky to be able to do that.