Nowhere to Run

Matt Connolly on Andy Warhol’s Vinyl

When discussing the film frame (as a boundary of visual perception as opposed to, say, a unit on a strip of celluloid), two elements tend to come to the fore. First, the frame provides a perimeter within which filmmakers can add, subtract, rearrange, and otherwise construct the mise-en-scène of a given shot. Which characters we see and don’t see; how objects and bodies relate to one another in time and space; what patterns of color, light, and shape form and change over the course of a shot—all of these and more become possible through the specific parameters set up by the length and width of the frame itself. Second (and perhaps somewhat more abstractly), the frame delineates the borders between the world of the film and the space within which it has been created. No matter how far the screen stretches or how completely the camera appears to explore a given arena, there comes a point where what allows the film to come into existence—the production equipment, the crew, the camera itself—remains just out of frame, a conceptual border beyond which we can only imagine as we sit in the darkness of the movie theater. In this way, the frame not only shapes the aesthetic possibilities of the film image, but defines the idea of the film itself as a constructed visual object whose very being necessarily depends upon artists and technicians whose decisions beyond the frame determines what goes before it.

Andy Warhol’s Vinyl (1965) remains notable for many reasons—its still-striking presentation of gay male S&M practice; its oft-forgotten status as the first cinematic adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, besting Stanley Kubrick’s version by six years—but its unsettling power can be most directly located in how it engages with (and slowly blurs) these two key elements of the cinematic frame. The film’s 1.33:1 (4:3) aspect ratio contains within its square-ish confines a tableau of bodies and bric-a-brac that constitutes Vinyl’s ramshackle diegetic universe, one that remains relatively unchanged by the few camera movements and cuts that occur over its 67-minute running time. Indeed, it might be enough to simply track how Warhol arranges his seven actors and various objects (a rolling chair, a trunk, a lazily rotating disco ball) within this almost-frozen frame, which can be bursting with visual activity one minute and then dominated by negative space the next.

Yet Warhol’s careful packing of the frame proves inextricable from his larger concerns. Like many Warhol films released in this period, Vinyl was shot at the Factory (Warhol’s studio-cum-social center in midtown Manhattan) with a cast of artists, performers, speed freaks, and hangers-on that partially formed the constellation of “Superstars” whom he would make famous over the course of the mid-to-late 1960s. His actors inhabited their roles in a very loose sense, drawing upon their own innate charisma and insecurity to hold the camera’s gaze; and Warhol would frequently stoke their private fears and interpersonal tensions to get the reactions he wanted on camera. These performances (combined with a virtually nonexistent interest in faithfully recreating Burgess’s novel on the part of Warhol and screenwriter Ronald Tavel) certainly help give Vinyl a self-aware quality, never letting us forget its status as a highly artificial rendering of Orange’s narrative. And yet, as the film begins to focus with ever-greater intensity upon the enactment of sadomasochistic scenarios, the ironic distancing built into Vinyl begins to morph into something far more unsettling. The registering of seemingly genuine pain onscreen transforms the frameinto a kind of mysterious inner sanctum, within which the performers inhabit a world somewhere in the shadow lands of actorly commitment and drug-infused trance. We know objectively that anyone could leave at any time, and yet they remain within these increasingly claustrophobic confines, watching and waiting for the next drip of candle wax or hit of amyl nitrate to launch them further down the rabbit hole. Then again, so do we.

Vinyl builds up to this séance-like atmosphere slowly, initially using the circumscribed space of the 4:3 frame to situate the performers in a tableaux of cool artifice. Vinyl opens with a tight close-up of its lead actor, Gerard Malanga, staring directly into the camera. He gazes at the viewer with a James Dean-esque squint, his parted lips suggesting something between seduction and vacuity. Just as notable as Malanga’s visage, however, is the claustrophobic manner in which the shot slices off parts of his face, with forehead, right ear, and chin all disrupted by the frame’s edges. The extreme proximity of the image proves somewhat of an anomaly in Vinyl’s overall aesthetic: within a few seconds, the camera slowly zooms out into a slightly high-angled medium-to-medium-long shot of Malanga, where it will remain for the majority of the film. The persistence of the frame being not quite able to contain the figures within it, however, continues once the camera settles into its primary view of the action. Flanking Malanga on his left are Tosh Carillo (sitting in the foreground), J.D. McDermott (lounging in a rolling chair) and Jacques Potin (almost not visible in the shadowy background), while Ondine hovers behind Malanga in the center background and Edie Sedgwick sits on a wooden trunk in the right midground. The frame cuts off much of Carillo and Potin’s bodies, as well as most of Ondine’s head—a visual looseness that correlates nicely to the actors’ own casual relationships with the characters they ostensibly portray. Carillo and McDermott eventually assume their roles as a police officer and doctor, but remain hanging about on-screen minutes before they officially enter the plot. Playing the lead role of Alex, Malanga does not begin to remotely inhabit the character until roughly four minutes in, after he completes a round of weight lifting as the others watch with varying levels of interest. And in perhaps the film’s most flippant take on the fluidity of performer and role, both Potin and Sedgwick are identified simply as “extras,” remaining within the frame for much of the film and interacting with the narrative to varying extents. In this way, Vinyl defines the frame’s imprecise boundaries as both indicative of visual style and symbolic of the slackened relationship between the reality of the production process and the illusion of on-screen narrative.

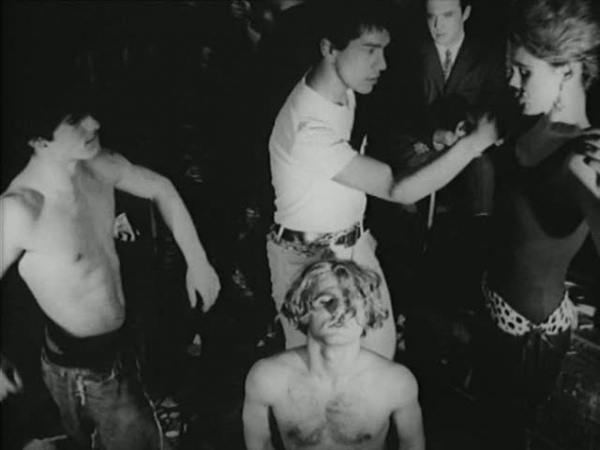

Even as Vinyl continues to underscore its mood of offhand reflexivity, however, it simultaneously begins to use the frame’s constricted spatial boundaries to unsettle the playful quality of its early moments. The “story” (such as it is) begins shortly after Malanga’s workout, when his Alex and Scum (Ondine) harass Pub (Larry Latreille) a youth carrying a pile of books. From Latreille’s haphazard entrance from the right side of the frame to Malanga’s stilted line readings as he and Ondine verbally accost Latreille and tear pages out of his “books” (really a pile of magazines), the entire scene functions less as the opening moments of a cinematic plot thanas the initial instance of male aggression and violence that will be developed and taken down increasingly darker paths. The distinction between Vinyl’s set as a loosey-goosey playground and a site of genuine S&M torture begins to blur once Latreille is led to the right background of the frame while Malanga returns to the center foreground. Malanga gives Alex’s personality-defining speech as a series of halting statements to no one in particular, full of Burgess-inspired slang that does not seem to sit comfortably in Malanga’s mouth. (“Okay, okay, I am a J.D. So what? I like to bust things up and carve people up and I dig the old up-yours with plenty of violence so it’s real tasty.”) Then, prompted by an off-screen radio or record player, he begins undulating to the beat of “Nowhere to Run” by Martha and the Vandellas. Sedgwick joins in the dancing after some initial hesitation, eventually waving her arms rhythmically in time with Malanga’s more aggressive hair whips and fist pumps. It’s a casually inexplicable and even charming interlude, even as the random, maniacal laughs of McDermott that punctuate the dance allude to a much darker parallel scene late in the film. If our eyes rest comfortably upon Malanga and Sedgwick throughout, though, they also cannot help but gravitate toward the right background of the frame, where Latreille has been stripped of his shirt and is being methodically tortured by Carillo (himself a real-life sadist). Latreille’s physical pain, it should be noted, falls clearly within the bounds of S&M practice, with hot candle wax and belts used against Latreille’s bare flesh. Regardless of one’s level of experience or comfort with sadomasochistic practice, the juxtaposition of Malanga and Sedgwick’s energetic cavorting and Latreille’s writhing just behind them via the frame’s tight composition raises unsettling questions about who we should be looking at and, by extension, where our attention and sympathies should be directed.

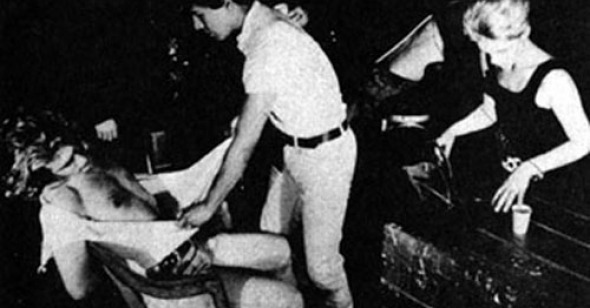

These questions come more explicitly to the fore when Malanga’s Alex falls into the hands of the police and (as in Burgess’s novel) undergoes a psychological reeducation through traumatic exposure to scenes of extreme violence, gore, and rape. Warhol and Tavel keep this conceit partially intact, but are ultimately far more concerned with what the viewers can see—namely, the torture of Malanga’s own body, tied to the rolling chair and subject to the S&M methods performed by Carillo. Playing the role of “the doctor,” Carillo asks Malanga to describe the various heinous images “screened” before his eyes. (Mind you, Latreille’s own torture continues in the right background, taken over by Potin and assisted somewhat by Ondine.) Still, it is the viewer of Vinyl who becomes witness to Malanga’s own chest being exposed when Carillo rips his shirt in half. It is the viewer who hears Malanga’s yelps when Carillo pours hot candle wax on him. It is the viewer who imagines the look on Malanga’s face when Carillo begins to lace him into a leather mask, the actual procedure occurring just off camera but Malanga’s screams clearly audible. Well, not just the viewer. Though she briefly leaves her perch on the trunk, Sedgwick remains a constant witness to both series of sadomasochist practices throughout the film—watching with an increasingly visible unease as Latreille and then Malanga become subject to Carillo’s various torture methods. (As if to underscore her implication as witness, Carillo at one point hands Sedgwick the candle that he was previously using to pour hot wax on Latreille’s chest.) Warhol further intensifies both Sedgwick’s queasy position and the viewer’s parallel experience through a modulation of the frame’s physically cramped staging. The middle of this once-bursting frame eventually empties, leaving a physical and visual gap between Malanga and Sedgwick. What results is a truly disquieting composition: Malanga’s body tied up on the left, his head sliced off by the frame as Carillo applies the leather mask; and Sedgwick slumped over on the right, as if exhausted by the very fact of witnessing Malanga’s writhing body and cries of pain. In shifting the frame’s composition from abundance to emptiness, Warhol visualizes our own sense of complicity with Sedgwick, her unwillingness to leave the frame despite her anxiety, mirroring the unholy thrall in which Vinyl’s displays of S&M torment holds us. (As J.J. Murphy contends in his invaluable study of Warhol’s films, The Black Hole of the Camera, “To understand Edie’s importance to Vinyl, one has only to try to imagine the film without her.”)

All previous elements—the visual and spatial constrictions of the frame’s edge; the off-screen music; the growing vulnerability of Malanga and discomfort of Sedgwick in their respective “roles”—come to a head in the film’s closing movement. Warhol echoes the close-up of Malanga that began Vinyl with the film’s only true cut, from the usual distanced framing to a medium close-up of Malanga, his head encased in the leather mask. (A more functional cut occurs halfway through the film; as with many of his other hour-ish films, Warhol let the 33-minute roll of film [roughly 1,200 feet] simply run its course twice, resulting in a brief disruption as the first roll literally runs out.) This startling contrast of Malanga at film’s beginning and climax becomes further amplified by the return of off-screen pop music, with a medley of contemporary hits running throughout Vinyl’s final minutes. Malanga is largely immobile, tied to the rolling chair and increasingly droopy after Carillo repeatedly administered him hits of amyl nitrate. As the Isley Brothers’ “Shout” plays offscreen, however, we note Sedgwick attempting to continue the lighter dance interlude from earlier. The tighter framing keeps our field of view primarily focused on Malanga, but we also see Sedgwick’s gyrating hand occasionally float into the frame from offscreen right—yet another striking variation on how Warhol uses the spatial boundaries of the frame to map Sedgwick’s conflicted reactions to the male aggression around her.

Her ability to negotiate her responses from a (tenuous) position of detachment falls away completely as the camera zooms out to resume its previously distanced shot scale and the film collapses into a trance-like debauch. Released from the confines of his chair, Malanga appears almost unable to stand after the multiple hits of poppers pushed on him by Carillo. He leans on Carillo in a kind of sinister slow dance as the Kinks’ “Tired of Waiting for You” drifts in from offscreen, though even this devolves into Malanga clinging to Carillo’s leg once he falls to the ground. Sedgwick, too, finally becomes entangled in the all-male space in these final moments: accepting a hit of amyl nitrate from Carillo; dancing uncomfortably with Potin; and hovering over Malanga as Carillo begins to cut off pieces of Malanga’s hair as the image slowly fades into white. The frame once again crowded with writhing bodies and suffused with music, Vinyl’s climactic moments envision a final movement into a drug and pain-infused drift—one pitched uneasily between the transcendence of moral queasiness and the descent into numbness.

In the end, Vinyl rests upon a series of entwined paradoxes. The film portrays scenes of physical torture that seem both controlled in their technique and frighteningly vivid in their effects upon the performers. These scenes become enacted by individuals who both are and aren’t their characters, mouthing dialogue and plot points that become infused with spontaneous reactions produced not through “connection” to the material but by the in-the-moment stimulus of physical pain, drugs, and interpersonal tensions. (Murphy notes that Warhol purposefully foiled rehearsals and added Sedgwick to the film as a means of throwing off Malanga’s performance.) And their work becomes contained within a physical frame that is at once highly permeable and strangely inescapable. These qualities all speak to the unique brilliance of Warhol himself, whose oft-cited remark that he would “just switch on the camera and walk away” when filming his movies exemplifies the sort of gnomic flippancy with which Warhol discussed his work yet contains a resonant kernel of truth when one considers the experience of watching a film like Vinyl. Warhol clearly thought about his films deeply, from the quality of his performers to the consequences of his minimalist formal choices. If we return one final time to the nature of the cinematic frame, however, we can consider how our understanding of production processes occurring just off screen almost always includes a vision of the director shaping the scene before the camera. Warhol’s cinema—and Vinyl proves exemplary—gains its power from this very effacement of directorial presence, the sense that the events unfolding before the camera (no matter how carefully conceived and executed) arise from the performers, from the situation, from the intangible forces of the cinematic apparatus itself. The frame becomes less a boundary separating the real and the artificial than a magic circle within which they blur together—a deceptively narrow space containing unstable, transfixing, frightening multitudes.