Rejuvenation:

An Interview with Zeinabu irene Davis (Compensation)

by Robert Daniels

Back in 1999 L.A. Rebellion filmmaker Zeinabu irene Davis won acclaim at the Toronto International Film Festival for Compensation, a form-altering, time-shifting Black romance about a deaf woman and a hearing man. Though the black-and-white picture would eventually garner nods at the Independent Spirit awards, like many other films by Black women directors (Drylongso, Almaâs Rainbow, Naked Acts, Losing Ground) it disappeared. Over the decades, Davis continued to teach at UC Davis and turned toward directing documentaries ranging in subjects from breastfeeding to jazz legend Clora Bryant. Compensation languished, awaiting rediscovery.

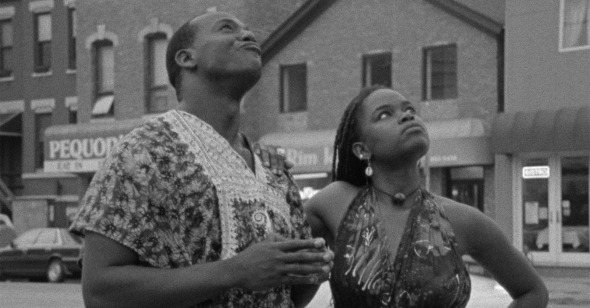

Adapted by Davisâs screenwriter husband Marc Arthur ChĂ©ry from the Paul Laurence Dunbar poem âCompensation,â the film is composed of two stories set in two separate decades. The first takes place in 1910: Malindy (Michelle A. Banks), a deaf educator and seamstress, falls for Arthur (John Earle Jelks), a Great Migration traveler who has just arrived in Chicago from Mississippi. Through their romance, Davis interrogates the socioeconomic divide felt by northern Blacks at the turn of the century, and uses archival photographs to document the eraâs bustling, cosmopolitan verve. Fascinatingly, the pictureâs 1910 portion is also a silent film, relying on intertitles to translate the spoken and signed dialogue. The contemporary sections take place in 1993. A hearing Librarian named Nico (Jelks) is dating the deaf artist Malaika (Banks). Through Malaika, Nico learns ASL, is introduced to deaf poetry clubs, and must contend with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In the modern-day setting, Davis makes a decision that feels ahead of her time: she uses closed captioning for all of the dialogue and sound, crafting a film deeply aware of the cinematic ableism that has existed since the pictures turned to sound.

For years it was difficult to see Davisâs sumptuous, nonlinear romance. It went unreleased on VHS and was only available on DVD through the crucial nonprofit distributor Women Make Movies in a copy akin to a burned DVD-ROM. Davis credits two people for bringing the film back. âRight before COVID happened in 2019, Ashley Clark, who was at BAM, did the series âBlack â90s: A Turning Point in American Cinema,ââ she explains. âAnd then Richard Brody at The New Yorker saw it and loved the film, calling it âone of the greatest American independent films ever made.ââ Along with recently being named to the National Film Registry for Preservation, the film has been rejuvenated in 4K with new captions and remastered sound. This version premiered at the New York Film Festival before arriving at the Chicago International Film Festival, where I spoke to Davis about Black representation in early cinema, the poem that inspired the film, and the family effort to bring Compensation back.

Reverse Shot: For decades, itâs been so hard to see Compensation. What have your primary aesthetic goals been for this reworked version?

Zeinabu irene Davis: First, I just want to say I havenât been calling it a ârestoration.â I've been calling it a ârejuvenation.â Part of the reason I'm calling it a rejuvenation is because restoration makes you think itâs been restored to what it once was, and itâs not. Itâs really a new film to me. For economic reasons it was shot on 16mm. But 16mm had certain limitations to it, the main one being optical sound. That meant it was condensed to a mono track, but I had 32 tracks of sound on Compensation. I slept at Maestro-Matic here in Chicago I would work on the sound from 6:00 p.m. to one or two in the morning, so we built this fabulous sound design that I could never have people listen to because it got squished down to optical tracks. But now with this 4K, you can hear what we were working on. Plus, when I initially designed the sound, I wanted there to be a full expression of it for deaf and hard of hearing audiences to actually feel the sound design. Deaf people can experience sound. But they donât experience it the same way we do. So, I pushed those vibrational experiences. Thatâs what Iâm hoping people will be able to experience with this new version.

RS: Can you tell us about the team that worked with you to bring this the rejuvenation to fruition?

ZiD: This rejuvenation has involved my family. My husband Marc [Arthur ChĂ©ry] wrote the film. Our daughters, whoâve grown up watching the film, got to participate this time around. Our youngest daughter was âMiss Eagle Eyeâ when we were doing the color correction. One of the things I try to pass on to other women filmmakers is you can make films and bring your kids into the process with you, which is what I learned from the other women in the L.A. Film Rebellion. Barbara McCullough, Julie Dash, Alile Sharon Larkin, we always had our children with us under the Steenbecks when we were editing or on set. So, my youngest one helped with color correction. She was seeing specks of dirt and stuff. Greg, who was the master color corrector, was like: We need to give this girl an internship. The oldest one, who plays harp and violin, helped me figure out how to caption the music for the film. That was the hardest part, imagining the captions. We had to walk this hard line. We canât burden the film with more text because weâve got these intertitles, and we don't want to kill people with even more words. So how do we include more text? We don't want to hit people over the head to tell them how they should feel about the music, but we also want to describe the music in a way that gets you to emotionally know what's going on.

RS: When I watched this new version, there seemed to be more open captioning. How did you aesthetically place them in the frame so as not to visually overwhelm?

ZiD: I worked with Alison O'Daniel, a hard of hearing filmmaker who made The Tuba Thieves. Alison did all this amazing work on The Tuba Thieves figuring out a new way of doing open captioning; she really pushed where to put these captions, like placing captions closer to the person speaking so that deaf and hard of hearing people know who the hell is speakingâsimple stuff that we should have been doing so long ago. For this rejuvenation we decided we would put the music captions in the upper-left-hand corner. The sound effects were going to go in the upper-right-hand corner. The text or the descriptions of the sound say how things sound. When the DJ, who's my biological brother, says âWeeeee funk,â we write out the word so it sounds like it as opposed to just saying like, âwe funk.â As opposed to just writing âchirping birds,â we write âmourning doves.â Alison says one of the things that bugs her as a hard-of-hearing person is when you see captioning and it just has music notes. It doesnât say what the music is. Is it a trumpet? Is it a trombone? What's the mood? So, we tried to answer that. My oldest daughter and one of her best friends from high school are both music majors; we sat down and tried to figure out instruments like the specific African drums that were used because, unfortunately, I was not able to get in touch with the original African percussionist here in Chicago. But they did figure it out. Iâm excited for people to see those additions. The film is like an onion. You can peel off those layers.

RS: It seems like you had a wealth of material to rejuvenate the film. Many of the other L.A. Rebellion filmmakersâfor instance, Charles Burnett with My Brotherâs Weddingâlost much of their original material before they were able to restore their works. How were you able to keep much of Compensation intact?

ZiD: My confession is Iâm a pack rat. I donât throw anything away. My husband and I have been carrying around boxes from L.A. to Yellow Springs, Ohio, to Chicago and back to San Diego. But Iâve also donated some of it to UCLAâs archives. I did keep the DAT tapes and UCLA had the 16mm mags for the audio. When we were going through the restoration for the audio, I was like, you know what, I have these DAT tapes. I like keeping some of this legacy material because when my students come to my office, they're like, what is this stuff in your office? I show them what we used to do with 35mm or 16mm film and what DAT tapes are, and theyâre always super fascinated because they can touch this stuff. But generally, I fortunately kept a lot of my stuff.

RS: You open the film with text from the Paul Laurence Dunbar poem âCompensation,â and the film is credited as an adaptation of it. What was the writing process for making the poem into a film?

ZiD: As part of the L.A. Rebellion, our ethos was to work with people from the community. I frequently cast people who basically play themselves in one way or another. The film I made before Compensation was a featurette called A Powerful Thang, in which one of my very best friends, Asma Feyijinmi, plays a single mom and a dancer. As a dancer from Brooklyn in the early 1990s, she was losing a lot of her friends to HIV/AIDS. I gave her a journal to write in as her character while we were filming because she had to wait as we put up lights and worked on the sound. I also gave her the poem âCompensationâ because we were shooting in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and Dayton, where Dunbarâs house is, is 20 minutes away. She responded to âCompensationâ from the viewpoint of someone losing men in her community to HIV/AIDS. When Marc and I read her response, which was really beautiful, we thought about Chicago. In Chicago in the early 1990s, one secret was how many more Black women were either losing their lives to AIDS or becoming HIV positive than were being reported, so we decided that we would talk about that in an oblique way.

RS: The silent portions, set in 1910, use intertitles and considers the effects of tuberculosis on that eraâs Black community. Did the Dunbar poem also inspire a look back into the past?

ZiD: As film students at UCLA, we were bludgeoned with having to learn Birth of a Nation. I mean, you go to any film introduction class, and they teach you that film. At the time they rarely talked about the inherent racism in that movie. Instead, itâs, Oh, look at these marvelous shots. There were other films that did the same shots and movements before, or even at the same time, but Birth of a Nation is always put up as a marvel of cinema. On the other hand, thereâs part of early cinematic history that African Americans contributed to that doesnât get taught. There are all these first images of cinema done by Edison with Black folks because they didn't know whether shooting film could affect peopleâs health. But many of those films are gone with only some chance at rediscovery. They only just found Something Good â Negro Kiss a few years ago. Compensation was a way to recuperate some of this lost history. When I made the film, we didnât have internet access to those photographs and to those reels of film. We had descriptions of films in archival copies of The Chicago Defender.

RS: While you were talking about reclaiming history, I was thinking about Jacqueline Stewartâs book Migrating to the Movies, which traces the growth of Black spectatorship from the pre-classical era to Blaxploitation. On the cover of that book is the scene from Compensation when Malindy and Arthur go watch a silent film. Film history rarely acknowledges that Black people have always been moviegoers. Was it important to reclaim that history?

ZiD: Chicago had such a significant role in the development of cinema, especially for Black audiences. At UCLA, we werenât really allowed, to some degree, to enjoy Black cinema or to think about Black people participating in the early parts of cinema. That moviegoing scene in the film was shot at Northwestern Universityâs screening room. The rejuvenation makes it so that you could actually see everybody in that sequence. Marc, my husband, is one of the spectators. You can see him in the very back-right-hand corner. To return to your question, I do think the moviegoing scene is important. Black folks do make up a big audience. Because of Blaxploitation, Black people are the ones who saved the cinemas in the 1970s. Iâm a child of the â70s. Iâm one of the little North Philly hood rats who was running into theaters watching all those Bruce Lee and Pam Grier movies sometimes to just get out the heat. I didnât imagine I would become a filmmaker then, but obviously seeing myself in scenes of those badass girls kicking booty was something that stayed in my psyche. Representation matters. I still think itâs necessary that we see ourselves onscreen.

RS: How did you find the filmâs lead Michelle A. Banks?

ZiD: That was a blessing. I was on a grant panel for Independent Television Service (ITVS), which at that time was in St. Paul, Minnesota. We happened to be looking at the free newspaper and there was a photograph of this beautiful dark-skinned Black actress who happened to be deaf. We went to see her perform at a theater. We stayed after the play was over and waited backstage. Because she didnât have an interpreter, when we talked to her, we wrote on a pad of paper to ask if she was maybe interested in being in a film. Luckily for us, she had been in a film with another Black woman, a deaf director by the name of Ann Marie Jade Bryant, so she said âyes.â After she agreed to be in it, Marc and I decided to further research the script by becoming more involved with Black deaf community in Chicago and by taking sign language classes. As we revised the script, we also sent it to Michelle for suggestions. We got to know Christopher Smith, who's the dancer in the film, and he introduced us to more deaf folks in Chicago. We got to know people in the Black deaf clubs too and learned and incorporated their experiences as much as we could.

RS: You finished the initial filming of Compensation in 1993, but it wasnât released until 1999. What happened during those six years?

ZiD: God bless my actors. They had a lot of patience with me because Marc and I initially wrote the film as a short. The original script was only 28 pages. But we always knew the film was going to have these archival turn-of-the-century photographs. I would go to the archives to gather the photographs, but because I was teaching during the school year, I could only go to the archives at the Chicago Historical Society, Howard, the Schomberg Center, the National Archives, and the Library of Congress during the summer months. I also had to find grant money to be able to do those research trips. As we added the research elements, the film expanded to 45 minutes. From there we added some more scenes to flesh out John Earl Jelksâs character, Nico. Marc, for instance, works professionally as a librarian. He had a friend who worked as a children's librarian that had a very hurtful situation where a white woman would not let him lead a story time session because he was Black. So, Marc decided to write some scenes where Nico teaches the kids ASL and leads story time. Also, the film was initially shot during summer, but when heâs walking to his ASL class past the Lutheran Church for the deaf, thereâs snow outside on the ground you just canât see it.

But back to your question, John and I had to go back so many times to add more over the years. And John will do just about anything. I love that brother so deeply. He hung with me when I had no money whatsoever. He just believes in the vision. Heâs going to be in this new film Iâm making about Sojourner Truth, Phillis Wheatley, and Marie-Joseph AngĂ©lique, the sister who burned down Montreal in 1731.

RS: Have you begun shooting that yet?

ZiD: We were supposed to shoot this weekend with John and Michelle in Akron, Ohio, but the rejuvenation of Compensation has delayed it. I did a test shoot with Michelle as Sojourner in a black box theater in Akron in May; it was the anniversary of when Sojourner gave the âAinât I a Woman?â speech. We were supposed to go back to film her arrival in Akron. See, when Sojourner came to Akron it was via a canal boat. This guy named John Malvin, who was a free Black man, made his money as a carpenter and he had a system of boats. Sojourner came on one of those boats. But yeah, John and Michelle will be reunited for this, and the scope will expand depending on what funding we can get.

RS: Youâve now had the chance to watch audiences see the rejuvenated version of Compensation at NYFF and Chicago International Film Festival. Many are seeing this film, in any form, for the first time. What has the response been?

ZiD: We were surprised. Honestly, I thought the people who were going to come see the film were going to be middle-age or older. But there were actually young people in their late twenties or early thirties, So I was like, Wow, younger people are coming to see this black and white film? I was really grateful. In New York we had a thing where high school kids came to see it. There were some from LaGuardia High School, some from another high school down the street, and some from France. I didnât know if they were going to be okay with the film. I asked them if theyâd seen any black and white movies. One brother in the back raised his hand and said he had watched Felix the Cat. Still, the screening went great. A few girls of color, Asian, Latin, and Black, came up to me afterwards and said thank you and told me they wanted to make movies too and hoped they can one day tell their stories. I told them theyâve got a cameraâtheir phoneâand to take a picture every day. Hopefully I'll see them at the New York Film Festival in another 10 years. That was my favorite audience. You just have to push them along so they can see what they can do. Youâve got to start somewhere.