Every Halloween, Reverse Shot presents a week’s worth of perfect holiday recommendations. Read past incarnations in our series “A Few Great Pumpkins.”

First Night:

Bram Stoker’s Dracula

As a greedy imbiber of short stories, I have little doubt in my mind that Poe is right, and that this is especially true of the Gothic tale: the overall effect of the perfectly tuned short story is one of totality, and the sensations it can drum up in the reader far outweigh those wrought by the novel. Certainly a short tale can be interrupted by the whistle of a tea kettle or a sudden chill up the spine, but entire meals, nights of sleep, even cross-continent excursions can rudely prolong the finishing of even the most gripping novel. The elegantly wrought short scary story, whether by M.R. James, Shirley Jackson, Algernon Blackwood, Ambrose Bierce, or Poe himself, can produce a single shudder strong enough to reverberate for years.

The Gothic novel is unlikely to maintain such an effect. Scattershot by design, it is made up of moments—images that, if the author is persuasive enough, sear the brain, but they remain building blocks in an overall narrative. Bram Stoker’s 1897 Dracula is perhaps the greatest example of a horror novel whose undying images keep it embedded deep in the cultural lifeblood more than a century later yet whose rather lumbering frame lays bare the shortcomings of the form. Thickly plotted and bound together with an epistolary conceit that increasingly becomes as nonsensical as any 21st-century found-footage horror movie (put the damn pen down, Mina!), Stoker’s novel nevertheless features standalone effects as terrifying as any ever written, even if most of them are contained within the book’s first 70 or so pages. Jonathan Harker’s exquisitely grotesque ordeal at Dracula’s castle in Transylvania could be, on its own terms, one of the great horror novellas, a description of evil befalling hapless innocence that grows more peculiar and beguiling with each turn of the page.

Shocks are strewn about the remainder of the book, from the lonely journey of the Demeter to the once-virtuous Lucy Westenra’s brutal demise, yet Harker’s sinister welcome and prolonged imprisonment remain the most compelling, claustrophobic passages, and always make for the best movie sequences. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), Browning’s Dracula (1931), and Fisher’s Horror of Dracula (1958) all peak in their opening passages, which offer a simplicity of effect and terror. Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula is the one adaptation that manages to strike a single sustained effect throughout, however, and it does so quite oddly, by moving away from damp, clammy terror and into a realm of lavish uncanniness—a flood of unrelenting sensation.

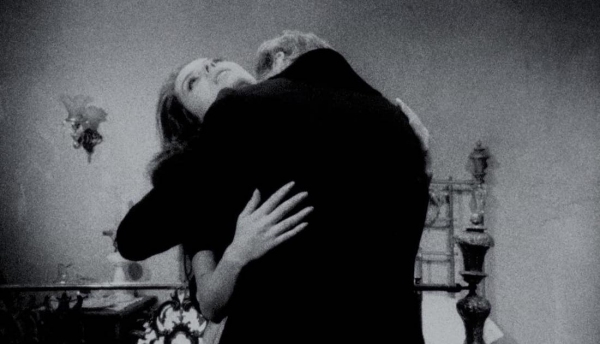

Departing from the novel, in which the Count looms mostly in the background, an abstract figure of menace, talked about more than heard, Coppola brings the devil front and center, transforming him into a lovelorn crypt-dweller who has “crossed oceans of time” to find his long-dead love, Mina (Winona Ryder). The swooning romance makes it increasingly unsettling—the more attached we become to Dracula (played by Gary Oldman as a chameleon, in both senses of the term), the more horrific his monstrous actions are. He’s still a demon, but one with a tragic backstory: a brutal Romanian knight of the “Sacred Order of the Dragon,” modeled on “Vlad the Impaler,” who renounces God after his beloved wife Elisabeta (also Ryder) is damned for killing herself in 1462. The film’s Constantinople-set opening, which turns Vlad’s ghastly slaughtering of Muslim Turks into blood-red shadow-puppet theater, may have set the stage for our current glut of unwanted origin stories, yet its bellicose power remains unmatched, setting the tone for a film that will refuse to play by generic rules.

I recall being overwhelmed witnessing Coppola’s film on opening night, November, Friday the 13th, in 1992. Rumor had gotten around in the press that the film wasn’t “scary,” which both supposed that being scary was a requisite for what he was trying to accomplish and presumed that fear isn’t relative. For this impressionable 13-year-old, Bram Stoker’s Dracula was indeed scary—terrifying, even—but not in any way I had ever experienced, and in a way I continue to find difficult to define. Though already something of a De Palma acolyte, I had yet to understand the Grand Guignol pleasures of the giallo, the beautiful excess of Hammer or Corman; whatever I knew of the Gothic likely came from John Bellairs books or Universal monster movies. Here was something that wasn’t just a lot—it’s a film that bears down on the viewer, lying on you with its full weight before sinking its teeth in. The fear the film instills isn’t from its oft-told tale but from the century it summons up like a beast from the deep. It’s movie as palimpsest, enriching its every screen second with genuflections to previous works, images, ways of seeing.

Coppola’s decision to achieve the film’s unceasing parade of effects in camera, forgoing CGI at the very moment of its all-consuming Hollywood ascent (Dracula was released in the year between Terminator 2: Judgment Day and Jurassic Park), has paid enormous dividends in its retrospective life. Every decision lends the film an eerie liminality between reality and nightmare: double exposures, live projections, forced perspectives, miniatures, superimpositions, all without computer or even optical printing technology. Actors occasionally were instructed to perform backwards during filming to give their movements a subliminally odd bearing; the final chase up the Borgo Pass to catch the Count before the sun sets has a lower frame rate that gives the climax the feel of an unearthed silent cowboy serial. It feels apt when, at one point, the Count, trying to woo Mina in London, asks for directions to the nascent Cinematograph: “I understand it is a wonder of the civilized world.”

Coppola has claimed every trick in the film could have been achieved at the turn of the previous century. Even if there was a teensy bit of post-production magic, Coppola’s film has the quality of Méliès hocus pocus, effects all done so off-handedly they feel like surreal imaginings caught out of the corner of your eye: the baffling horror of Dracula crawling up the side of his castle like a lizard, the frightening beauty of a shadow knocking over a candle as though a slight breeze. Coppola’s choices put him at odds with his special effects department, whom he fired and replaced with his magic-loving son Roman. (It’s a similar tale of behind-the-scenes nepotism as this year’s long-gestating—and, somehow, way hokier—Megalopolis, which saw Coppola dissolving his effects team during production and replacing them with his nephew, Jesse James Chisholm, a VFX supervisor on multiple Marvel films.)

Employing only live effects was a way of fusing Stoker’s novel to its historical moment, as it was published in the first full decade of cinema. (The film’s year of release marked exactly one-hundred years since Thomas Edison began constructing his Black Maria studio in West Orange, New Jersey.) The filmmaker saw his horror opus as a chance to connect to a cinematic tradition rather than “update” a story for the era in which he was working. Though in the film’s bodice-ripping one can see a kinship with the nineties’ erotic thriller, Coppola does achieve an unmistakable timelessness. Some moments seem familiar from our shared cinematic past: when Oldman’s Count emerges from his box of earth below the Demeter, he hydraulically rises directly to the camera, the top of his head slightly cut off at the top of the frame—just like Max Schreck in Murnau’s film. Others appear to be borrowed from Coppola’s own filmography of violence: recalling The Godfather’s baptism sequence, Lucy’s final, fatal ravishing by the Count is intercut with Mina and Jonathan’s wedding, the waving of the ceremonial incense thuribles and Latin chanting contrasting with torrents of expressionistic blood, which cascade across Lucy’s boudoir as though heaved from the Overlook elevator.

Every choice works in diabolical concert with the next, a complete vision as equally vivid in Eiko Ishioka’s gonzo Victorian costumes as in Greg Cannom’s snaggle-toothed beast makeup as in composer Wojciech Kilar’s blasts of triumphant evil. The film feels less constructed of standalone sequences than of a single sensibility, ever flowing. With one dissolve, a peacock feather becomes a tunnel heading toward the Carpathian Mountains. In a single cut, a decapitated flying head matches a sliced roast of beef served at a restaurant. Fear is ecstasy, and love is terror. Our doomed couple is, finally, enraptured by elusive death and immortalized in stained glass. It is a work of pure totality of which Stoker might only dream. —Michael Koresky

Second Night:

The Mask

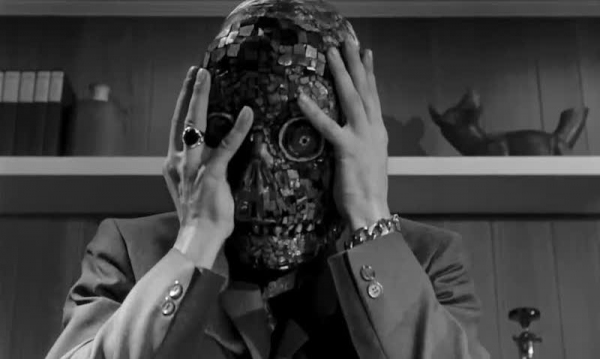

Love comes in at the eye. Two decades before Max Renn donned a helmet to record his hallucinations at the offices of Spectacular Optical in Videodrome, another Torontonian patsy found himself stranded in the uncanny valley beneath a cumbersome piece of headware. All hail the spectacular optics of The Mask, the first Canadian horror movie filmed—even if only partially— in 3-D! The title of Julian Roffman’s 1961 shocker refers to a cursed Aztec artifact that regresses its wearer into a welter of violent, primal impulses, roaming the streets in a fugue state while searching out potential victims for rape and murder. Like any good Lovecraft riff, the narrative focuses on a rational skeptic—in this case, Dr. Allan Barnes (Paul Stevens), a frowny, buttoned-down big-city psychiatrist. Barnes’s refusal to believe in the mask’s reality-altering properties is built on starchy smugness, which melts away the moment he decides to take a peek through the mask’s gaping eye sockets.

The making of The Mask is the stuff of local legend, stemming from a fateful meet-cute between Roffman, a New York born documentary filmmaker who decamped to Canada to chronicle the country’s armed forces training programs circa World II, and Ontarian theatre-chain mogul Nat Taylor, one of the pioneers of North American multiplex exhibition. (Taylor had a hand in the construction of the Eaton Centre, which opened in the late 1970s and briefly housed the world’s largest multiscreen cinema.) The pair’s decision in the late 1950s to collaborate on a pair of American-style exploitation movies, each torn from the low-budget, high-yield playbook of Roger Corman, was very much in keeping with the English-Canadian tradition of discount genre knockoffs. But where their previous film, the grisly beatnik-themed thriller The Bloody Brood (1959), starring Peter Falk, was cobbled together with minimal hassle, The Mask’s formal conceit of toggling between conventional cinematography and “Depth Dimension 3-D” required elaborate planning—including cameras loaned from the U.K.—and input from veteran Hollywood studio hands like Slavko Vorkapich, who specialized in creating elaborate montage sequences. (The latter received a screenwriting credit even though his proposals were ultimately deemed too expensive to properly realize.)

As a cheesy slab of B-movie storytelling, The Mask has its moldy charms, although the acting isn’t one of them (future soap star Stevens makes for a singularly miserable leading man). Its classic status is almost completely predicated on the tension between the 2-D and 3-D sequences—a disparity juxtaposing plodding semi-competence against suggestive surrealism inspired by the anatomical artwork of Andreas Vesalius. The mask-driven interludes manifest at regular intervals as impoverished but vivid fever dreams—a labyrinth of smoky interiors, hovering skulls, and surprisingly ferocious psychosexual symbolism. The structural trick dictating that the viewers only don their 3-D glasses in sync with the hapless protagonist—a command literalized via a booming bit of voice-over narration repeating the phrase “put the mask on now”—meanwhile splits the difference between William Castle-ish gimmickry, belt-tightening cost-consciousness, and a genuine conceptual coup—one that served, however unconsciously, as an allegory for the aspirations of an entire filmmaking cohort. At a moment when Torontonian movies of any kind were still fairly uncommon and the city was rarely put on display outside of a nonfiction context—a byproduct of a nation’s dolefully vaunted “documentary tradition”—a sensationalistic production predicated on mapping and navigating interior (i.e. studio) space vibrated with a sense of possibility.

In its own modest but ambitious way, The Mask is a visionary work awakening Canadian directors, audiences, and critics to the act of seeing with their own eyes. In a world where Videodrome’s CIVIC-TV actually existed, Roffman’s tricky little treat would warrant an annual midnight transmission on Halloween. —Adam Nayman

Third Night:

Arrebato

“Keep in mind that I still believed in cameras that filmed, the things that are filmed, and in projectors that projected.” This is when Pedro (Will More) passes the point of no return in Iván Zulueta’s Arrebato (1980), turning to a more metaphysical form of filmmaking. Can cameras pierce the logic of the visible world? And if they can see something we can’t, what kind of agency do they have?

Later in Arrebato, we actually see a camera autonomously swivel on a tripod, speeding up the pace of its automatic shutter all by itself. Though many horror films dwell on the creepy details of raw found footage, Arrebato is more frightened of the inherent evils in editing: Pedro turns this camera on himself while asleep in his claustrophobic Madrid studio, and the machine stops filming him whenever he stirs. In fact, it self-censors, blotting out the subsequent frames with splotches of red. Arrebato was made in the post-Francoist thaw, so a film maudit seems a resonant topic for a horror film, reflecting an anxiety about accessing something that’s been kept under wraps. But Pedro, an addictive personality, wants more. He wants to sink into those gaps, to fully surrender himself to the camera while asleep. In turn, the red of the film stock looks eager to swallow Pedro up.

A 27-year-old amateur filmmaker whose lifestyle suggests Rimbaud with Peter Pan Syndrome, Pedro had been living with his mom in an estate in the Spanish countryside, where he obsessively made skittering 16mm films of the house and its grounds. His shorts are reminiscent of American structural cinema—they are also Zulueta’s own experiments from a few years earlier, clearly indebted to a formative jaunt to New York in 1963—and he’s drawn especially to the interplay of light and shadow, to inducing sped-up time. The films cut deep for Pedro, making him cry hysterically; he crumples into himself in sudden outbursts that are unnerving in their impenetrability. After a while, these bursts of feeling are no longer as intense for Pedro, and he wants to push deeper into his craft. When his cousin Marta (Marta Fernández Muro) brings home José (Eusebio Poncela), a disillusioned director of schlocky vampire films, Pedro intuits a kindred spirit, even if José postures as bemused by Pedro’s eccentricities. The filmmaker seems to materialize on José’s guest-room mantle, watching him sleep, just like the camera that eventually consumes Pedro: maybe the watcher is the sleeper’s gateway to a higher realm of consciousness, offering a vampiric bite that induces death and transformation.

At first, Pedro asks José if he has tips for filming at a “precise rhythm,” to push beyond the visible, but they fall into a homoerotic bond fueled by heroin—also central to production delays and budget troubles on Zulueta’s set; most, if not all, of the drug use in the film is unsimulated. (It’s no mere affectation for Pedro to wear a heavy winter coat in the Spanish summer.) The film is about chasing trancelike highs—“arrebato,” or “rapture,” is a state of enthralled, nonverbal grace that Pedro seeks in his filmmaking. Susceptibility to “arrebato” is also how he vets new acquaintances; he leads José, and later his girlfriend, Ana (Cecilia Roth), into a bedroom decorated with childhood knickknacks and tries to find the perfect object to hypnotize them. For José, it’s a set of trading cards, popular in Spain when he would have been a kid; for Ana, it’s a Betty Boop doll. Ana seems particularly unreachable as she drifts into her own world, slumping in her seat and staring at the doll for hours on end. A creepy lullaby motif with nursery-friendly xylophones and baa-ing sheep crescendos as the characters slide into their rapture. In childhood, the music seems to say, logic was less important than totalizing magic.

The alienation of addiction shapes Arrebato’s eerie mystique: José and Pedro have this hermetic connection, but they also travel down roads that they cannot articulate to anyone else, withdrawing from well-adjusted adulthood into pure sensation. Their desire for transgression coalesces with the punk explosion of La Movida Madrileña, amid liberalizing attitudes toward sex and drugs—and Pedro eventually moves to the epicenter of that moment, Madrid, hungry for more material. But he also starts lashing out more unpredictably, metamorphosing into a vampiric, red-eyed, unsleeping creature-of-the-night. In one of the film’s most ominous ellipses, one of his hookups flees his apartment covered in bloody scratches. Inevitably, Pedro secludes himself as he starts filming his slumbers. His possessed camera could be a paranoid hallucination, but if it is, it’s a collective one. When Marta visits Pedro, she disappears without a trace; when the film is developed, she vanishes in a jump cut, which Pedro takes as proof that she’s been devoured by the camera.

Zulueta encourages this shared-nightmare reading, entwining reality, memory, and fantasy until the distinctions are meaningless. We’re aligned with José’s perspective, but his thought process is shaped by a whispered voiceover from Pedro, an Edgar Allan Poe–esque letter detailing his descent into madness. He’ll speak to Ana, but Pedro’s voice will crescendo over hers in the sound mix; the music from Pedro’s films often turns out to be records José is listening to in his flat while coming out of a high. This slippage into a seductive artifice, out of the real, is what both Zulueta and his characters crave—José drapes colored blankets over his lamps to create makeshift gel lights, as though movie-fying the mundane. In an earlier short that now seems a preliminary study for Arrebato, Leo es pardo (1976), Zulueta sees if film can awaken, even possess, quotidian surroundings; his Méliès–esque editing makes it seem like an apartment’s doors are opening and shutting on their own, quick enough that the slams sound like machine-gunfire. This may be a housebound short centered (again) on a drug trip, but Zulueta alights on details that open up the space—a tantalizing slice of unreal-blue sky beckons to worlds, realms, apart from daily life.

José eventually seeks out Pedro’s flat, where his sort-of amour has disappeared, the camera clinically fixed on his empty bed, its sheets rustled. With nowhere to go but into Pedro’s abyss, the only option left is to lie down, offer himself up to that kino-eye. How could he not? José trembles as he blindfolds himself, frightened of what might happen to his mortal form, but also steeling himself to pass beyond vision. A final warning: Pedro’s disembodied narration was not recorded by More, but Zulueta, inviting any susceptible viewers into that terrifying, isolating, irresistible unknown. —Chloe Lizotte

Fourth Night:

The Stuff

I was first aware of The Stuff from video rental store visits, where the VHS box art of a suffering man’s head bursting with some kind of awful marshmallowy ooze menaced my preteen self alongside The Ghoulies, Dead Alive (those awful stretched licorice lips), 1985’s House (the skeletal doorbell-pushing hand with the tagline ‘Ding dong, you’re dead’) and of course Popcorn (“Buy a Bag—Go Home in a Box”). This 1985 thingamajig from Bronx-raised, dollar-bin-Hitchcock Larry Cohen, grazes “Great Pumpkin” status through the sheer novelty and relevance of its central anti-consumerist conceit, its Simpsons-esque diegetic fake TV ads, inspired makeup and effects, and a handful of game performances from a semi-stacked cast, even if the sloppiness of its execution occasionally befuddles. According to Cohen, the film’s tonal disunity can be chalked up to that perennial bugbear, studio meddling. The new brass at New World Pictures, sold off by founders Roger and Gene Corman shortly before The Stuff’s production, purportedly expected a fast-moving, straight-ahead gory horror movie, and were dismayed at the impish satire-with-scares when screened, forcing heavy trimming at the expense of connective tissue and coherence.

Still, there’s a great film lodged somewhere inside the goo, and while it may not reach the heights of Cohen pictures like 1974’s It’s Alive (with its Bernard Herrmann score, Rick Baker f/x, and powerful leading performance by John P. Ryan), the genuinely upsetting God Told Me To (1976), or the salacious, liberty-taking American history lesson The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977), it nonetheless carries the artist-huckster’s distinct stamp. There is no belabored origin story for the titular Stuff—an old codger in some sort of mining labor yard just finds a pool of the white mess bubbling away one night and decides to taste it (as one does), declares the taste “good” and immediately remarks to a coworker that they could make a fortune selling it. By the next cut, The Stuff has already conquered the marketplace with its addictive deliciousness and the blanket saturation of its advertising. We then meet a rebel kid, Jason (Scott Bloom), who, after seeing some Stuff shimmying inside his refrigerator, starts a revolt of one against it that involves trashing a grocery store and eventually doing battle with his Stuff-mad parents and brother. On a yacht off Manhattan, some junk-food execs announce their plan to hire former FBI agent turned industrial troublemaker Mo Rutherford (Michael Moriarty) to find out more about The Stuff in hopes of denting its market dominance. Mo joins forces with ice cream mogul “Chocolate Chip” Charlie (Garrett Morris) and Stuff advertising executive Nicole (Andrea Marcovicci), and eventually Jason, too, to destroy The Stuff, which he has discovered is in fact a deadly parasite that takes over the brains and weakens the bodies of its hooked consumers.

The Stuff’s brisk production didn’t leave time for rehearsals or luxuries like sync sound, so much of the dialogue has the deadened, uncanny quality specific to ADR—ideal for a world in which humanity is being scooped out and replaced by what it’s putting in its stomach. Every statement and movement is so odd that, as in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, you’re never sure who’s been Stuffed. Like Danny Aiello’s Stuff-approving, bought-and-paid-for FDA agent, who wears a three-piece suit while relaxing in his house and who explains to Mo that he and his giant “puppy” Ben (“I feed him well”) both swear by the goo, until Ben goes on a slimy rampage. SNL legend Morris’s boastful wisecracker Charlie seems the most lifelike (quipping more than once that his hands are registered as lethal weapons) until Charlie, too, winds up a Stuff puppet. While much of the film is too goofy to be truly scary, Jason’s parents (Frank Telfer and Collette Blonigan) genuinely unsettle, as when the father tries to reassure his cynical tot that it’s normal for humans to eat living things, citing (correctly) live bacteria in yogurt and yeast organisms, adding in monotone with a robotic grin, “They kill the bad things inside us.” Later, in praise of their Stuff diet, he enthuses, “We don’t need to sleep anymore!” Blessedly, Mo eventually traffics young Jason across state lines and away from his grotesque kin (though not out of harm’s way).

Of all the performances, Moriarty’s Mo seems the most beamed-in from outer space. A repeat Cohen collaborator—see also Q – The Winged Serpent, It's Alive III: Island of the Alive, and A Return to Salem's Lot—the actor best-known as the Executive Assistant DA on the OG Law & Order and for his cranky right-wing blog posts composed from Canada, to where the Detroit-born actor expatriated as a “political exile,” Moriarty here makes some Choices. Most noticeable is his accent, a laconic “Southern” drawl that comes and goes and is supposed to rhyme with his knee-high cowboy boots and receding shock of reddish hair (a wig?). Never as cool or charming as he clearly thinks, the tall Moriarty does provide unpredictability, as when he slugs one of the yacht-meeting suits without motivation, or when he’s able to seduce Nicole. That seduction is abbreviated when, in their motel room, some Stuff explodes out of their pillow (??) and, Facehugger-like, latches on to Mo’s head, prompting Nicole to set it ablaze like a Baked Alaska (fire is The Stuff critters’ plutonium). During this melee, a random passerby joins the fracas for some reason, only to get blasted against the wall with Stuff in an effect that employed the same revolving room effect as A Nightmare on Elm Street, filmed a few months prior.

The marketing of the gloppy treat showcases The Stuff is at its wryest and most creative, starting with its annoying jingle (“E-nough is never enough, for The Stuff!”) reminiscent of the like-minded Halloween III’s Silver Shamrock song. Best is a TV spot featuring Abe Vigoda who, dining out with his wife, asks in an exhausted drone, “How’s the food, sweetheart?”, to which the wife slams down her cutlery and pouts, “Where’s da Stuff!?” In a rambunctious third act that doesn’t quite work, Mo recruits a retired US Army Colonel (fellow future Law & Order cast member Paul Sorvino), now a militia leader operating out of an upstate New York compound (played here by the Mohonk Mountain House), to help destroy the Stuff source. The Colonel is a liberal- and “commie”-hating cuss (and racist towards Charlie in an off-key, fun-deflating note) who apparently also feels strongly about strict food safety regulations.

The film is redeemed in a righteous penultimate scene in which Mo forces the two top Stuff execs to eat a full pint of their own deadly product, asking them, in something like the film’s thesis statement, “Are you eating it, or is it eating you?” before a shot of a standalone Stuff restaurant, sandwiched between fellow garbage purveyors McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken, being detonated. Mo, Jason, and crew may have succeeded in ridding store shelves of The Stuff, but a last moment shows that, since the demand’s been created, the goo will continue to flow in the black market. The rest of Cohen’s film could have used a bit more of this angry disdain (and real-world name-naming), but that’s a quibble—it is stuffed with enough smart satire and rabble-rousing energy to make it much more than just the gross-out exhibition promised by its VHS cover. —Justin Stewart

Fifth Night:

Cuadecuc, vampir

Your specific reaction to Cuadecuc, vampir might depend on what sort of a cinephile you are, but any kind of cinephile will have a strong reaction. The film is uncategorizable, so naturally it has been categorized in numerous ways: documentary, horror, experimental/avant-garde art film, behind-the-scenes featurette... What it is, though, can only really be answered in concrete terms: it’s a one-hour black-and-white silent film composed of 16mm footage shot by the noteworthy Catalan filmmaker and political activist Pere Portabella during the filming of Jesús Franco's 1970 chiller, Count Dracula (starring Christopher Lee). The title comes from a Catalan term meaning both a worm’s tail and the end of a reel of unexposed film stock. Jonathan Rosenbaum—no fan of Franco or his Count Dracula—justly described Cuadecuc, vampir as “one of the most beautiful films ever made about anything.”

Where the film swiftly explodes any “DVD-extra” expectations is in the choice by Portabella to assemble this footage so that it chronologically tracks the narrative of the Dracula story. Were this film to be seen entirely out of context, it would resemble a vividly experimental and ineffably gorgeous adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel. By filming (from a point of view adjacent to Franco’s camera) sequences from Count Dracula as they are being shot, Cuadecuc, vampir presents silent extracts of what appear to be—but are not—monochromatized rushes, juxtaposed with takes containing evidence of the film crew doing their work while the narrative sequencing continues unabated. So, we see production assistants filling the woods with smoke as the enchanted carriage approaches Dracula’s castle; an anonymous (as if disembodied) hand controlling a device which creates cobwebs to cover the castle door and Lucy’s corpse; and occasionally the entire crew, including their lights and sound equipment, slides into view, as Portabella widens out a shot of the main action. None of these line-crossing moments are underscored or punctuated by any break in the soundtrack: everything is fluid and unexplained. Sequences of high drama from the Franco film (such as the struggling infant in the sack gifted by the Count to his three vampiresses) become passing details shot from distance in vérité form, contributing to a pervasive discomfort that is far removed from the fear dynamics of the main event.

As such, Cuadecuc, vampir 's impact is not only a narrative one but also audiovisual and political. Much of it is shot on high-contrast film—nothing gray—which requires plenty of light (a process used by architects for projections of drawings), and an optical printer appears to have been employed to accentuate this destabilizing effect further in a number of sequences including the opening titles. Thematically, the line between the real and the unreal explored by both Stoker and Franco is apotheosized here by Portabella, who creates a new fiction from a nonfictional treatment of an existing one. As audience members, we are comforted to some extent by our genre familiarity—Franco’s film tacks very closely to Stoker’s plot—but we are also relentlessly and exhilaratingly unglued by the constant uncertainty of the extent to which the actors are in character, or of how the story is really unfolding, even as it is being rehearsed or created.

Portabella’s film career is little known outside of Spain owing to his having worked exclusively during the dark ages of General Franco, whose government for years forbade him from leaving the country for the sin of having produced Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana. He was determined with Cuadecuc, vampir and its valuable sister piece, Umbracle (shot in the same manner as Cuadecuc, vampir, but with sound), to create art which worked against the grain of sanctioned, Francoist commercial cinema. Even if the lavish, Technicolor Count Dracula itself was an acceptable example of the latter, Franco J’s own decision to allow Portabella free rein with his project shows how little he respected the protocols within which he was working. The soundtrack of Cuadecuc, vampir consists of bursts of musique concrète by the avant-garde polymath Carles Santos, fueled by the sounds of animals and machines and punctuated with uncanny silences—a soundscape which clashes and blurs like a hypnosis video. The only words heard are spoken by Lee himself, reading from Stoker’s Dracula in the film’s coda, breaking briefly and disarmingly into perfect French to signal his frustration at a failed take.

So why watch Cuadecuc, vampir on Halloween? Because it is a treatment of horror which examines and elevates the sensations one normally experiences when watching horror: the sense of anticipation, of mystery and bewilderment, and fascination at extraordinary and uncanny imagery, conjured here by a potent mix of pure classicism and pure innovation. Transported as we are by this unholy spectacle, it only takes a wink to the camera from German actress Maria Rohm (Mina/herself) to jolt us back into a recognition that we are bearing witness to the creation of art, and of a process entombed here in the sensory experience of the overall. The effect is of the film becoming unbound from its subject and pressing on, like the phantom carriage itself: not possessed, but free to float and drift where it will, and to take our inquisitive souls with it. —Julien Allen

Sixth Night:

Tall Shadows of the Wind

In 1976, Houshang Golshiri, the famous modernist Iranian writer and free speech advocate, published a collection of short stories called My Little Chapel. These included “First Innocent,” a story written in the form of a letter from the narrator to a relative about strange happenings in a village where he’s newly arrived. A literary icon of the second half of the 20th century, Golshiri was renowned for his experimentation with form, often creating within his stories a novel sense of indeterminacy and ambiguous meaning, and using various voices and perspectives within the narration. Filmmaker Bahman Farmanara became the preeminent cinematic translator of Golshiri’s style, collaborating on the adaptation of the critically acclaimed Prince Ehtejab (1974), which won the Grand Prix at Tehran’s Third International Film Festival and screened internationally. While scholars of Iranian horror cinema have retroactively pointed to horror elements coded into Farmanara’s breakout film, five years later, Farmanara and Golshiri would collaborate on a real chiller, adapting “First Innocent” into Tall Shadows of the Wind (1979), a major title of the Iranian New Wave, and an in-your-face allegory so transparent it was banned before and after the revolution, apparently spooking both regimes.

Composer Ahmad Pejman’s classical score does more than hint at impending doom in the film’s opening credits before we cut to a rural community at its knees. This small village is desperate for a miracle. The camera pans across their faces as they pray in unison for aid from above. “May he come help us…” they chant monotonously. We cut to the gaping maw of a cave, and as the villagers continue their chant, begging for happiness and justice, we’re pulled toward the darkness by a slow zoom. A group of men erect a scarecrow in the fields as if raised by the villagers’ eerie incantation. “May he come to solve our riddle,” the community chants. What that riddle is, exactly, is a question that hangs over the rest of the film.

After that creepy preamble, a bus drives into the village down a winding path before breaking down on the dirt road. The driver, Abdullah, leaves the bus, walks to an open field, and gradually approaches the scarecrow he sees in the distance. With a piece of coal, he gives it a face and offers up his hat, turning the faceless puppet into something resembling himself. Not long after, a series of paranormal activities around the village—a woman found convulsing in the fields, strange bumps in the night, and a rumored immaculate conception—lead the small community to believe that the scarecrow is both the culprit of their worst fears come to life and some form of their prayers answered: a punishing, all-powerful God.

Tall Shadows of the Wind is a film in which the most bone-chilling scares are metaphorical (the villagers submit to the stuffed, inanimate being with virtually no prompting, maybe the most frightening thing of all), but it is definitely trying to scare you. The first time we see the scarecrow after it’s created is in a quick cut to the rearview mirror of Abdullah’s bus, and there are many more jumps like this. The women of the community are most affected, behaving almost like zombies in its thrall, driven to seizures and even miscarrying from fear. How quickly faith can curdle into fanaticism and conspiracy, the film seems to say.

Released near the end of the Shah’s reign, Tall Shadows of the Wind was seen as a political critique of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi for his dictatorial control. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979 brought about even stricter codes of censorship, the film was again pulled from theaters in Iran, this time for its depiction of a revolt that occurs in a surrealist dream sequence at the end of the film, involving uniform red dress and red flags, perceived as pushing a Communist agenda.

There are symbols everywhere for those with eyes to see. In a beautifully composed shot in the first act, we see Abdullah playing with two small children, standing against a backdrop of a clay house with a violet blanket hanging out the lip of the window and identical red garments hanging from the clothesline. The kids are also dressed according to the motif with pink and purple shirts. The rusty bus, within the frame, has hints of red in its chipped paint, and red strings of yarn and fabric hang from a fence in the foreground. Genre cinema has long been a playground for independent filmmakers looking to communicate thorny political messages through their films, that are hard or even forbidden to say, from Don Siegel’s body snatchers to George Romero’s zombies. Farmanara’s scarecrows belong in the same canon, as a potent supernatural metaphor to manifest real world societal fear and paranoia. —A.G. Sims

Seventh Night:

Drag Me to Hell

From childhood to middle age, I’ve been cursed by enough movie images for a lifetime of sleepless nights. But even the worst—the diabolically animate clown doll of Poltergeist, Mr. Barlow popping out of the pitch dark in Salem’s Lot, Jack Torrance heaving that axe through the bathroom door, The Blair Witch Project’s amateur filmmaker closely studying that basement corner—feel like sweet dreams compared to a certain passage from M. R. James’s 1911 story “Casting the Runes.” It concerns Mr. Dunning, a solitary bachelor, like most of James’s protagonists. Unbeknownst to him, but increasingly clear to us, an evil hex has been put on him, and he has begun to feel uneasy, as though he is being watched or followed. He has returned late to his lonely house; his housekeeper has gone. As he settles in for the night, his bedroom is uncommonly dark thanks to the odd lack of streetlights outside the window.

A warning to the curious who keep reading, both for those who might want to experience the short story without spoilers and those who would prefer to sleep comfortably in their beds hereafter. “He put his hand into the well-known nook under the pillow: only, it did not get so far. What he touched was, according to his account, a mouth, with teeth, and with hair about it, and, he declares, not the mouth of a human being.”

Nothing more occurs in this sequence, other than Dunning’s quick exit. He spends the rest of his “miserable night” in a spare room, listening and looking for signs of an intruder, human or otherwise.

An antiquarian, school provost, and storytelling sadist, James was the unparalleled master of the abrupt, foul shock. His preternatural gift for tension and release would prove more influential on the scare tactics of horror cinema than other literary fear practitioners like Lovecraft or Blackwood, whose works were less predicated on momentary revelations and hair-raising blasts of terror than permeative, otherworldly sensation. James gives you just enough to arouse fear (or nausea) and then slams the door or casket shut. James’s description of “a mouth, with teeth, and hair about it” buried beneath the safe slumber of one’s pillow registers all kind of universal fears—putting aside gay panic, of course, a recurring subtext in James's work. This single sentence from “Casting the Runes” stays with me, and I think of it almost every time I put my hand under my pillow—meaning every single night. The only thought that always helps alleviate its terrible effect is my subsequent musing at how tough it would be to re-create this shock on screen.

The limits of horror movies’ capabilities are well demonstrated by this passage. It’s not an image, but a feeling, in the quite literal sense. The sensation of touch—and its violation—is paramount to James’s writing; horror movies, with their predilection for viscera, can try and evoke the effect of touch, but they will always fall back on the oppressed mind. This may be why horror movies about trauma seem to have gained such momentum in recent years—it’s not that difficult to approximate someone’s headspace, via performance or visual gimmickry. So, while you can try to make a viewer grasp a character’s anguish or sadness, it’s nigh impossible to get us to feel what someone feels with their hands.

In Night of the Demon, his 1958 loose adaptation of “Casting the Runes,” Jacques Tourneur doesn’t even try and recreate this moment. And thankfully: one can only imagine how silly a fanged beast in bed may have looked on-screen, especially considering the infamous, producer-imposed rubber monster that opens and closes the film. Tourneur’s film avoids any attempt at haptic horror, mostly engaging the viewer on the same level of atmospheric dread as in his eerie low-budget forties films Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie. In the movies, what’s off-screen is often scariest. In James’s work, what’s scarier is the description of the pestilent, unfathomable being that has reached out and penetrated our world.

All of this is preface to pay tribute to Sam Raimi’s 2009 Drag Me to Hell, which is about as far in temperament as one can seemingly be from either James or Tourneur. Nevertheless, this amped-up, even looser 21st-century version of “Casting the Runes” employs the basic principles of horror as established by James a hundred years prior, using Raimi’s patented brand of gonzo gross-out to bring the viewer into a place of palpable fear. A movie could never be as effective as the written word in demonstrating what it’s like to suddenly find your fingers exploring a hairy, fanged mouth under your pillow, but few other films are as accomplished at making the nightmare world of the cursed so tangible.

Raimi doesn’t try and recreate James’s most nauseating effect, either, but Alison Lohman’s jinxed bank loan officer has her own problems in bed, including getting vomited on by an uninvited guest’s mouth full of maggots and worms. Like Mr. Dunning, she’s going through a series of daily plagues, all part of the evil spell that will lead to her death. In James’s tale, Dunning is cursed by an ill-tempered, wealthy witchcraft dilettante, angry that Dunning was the final decision on a committee that refused to present his paper at an academic conference. (For an editor like myself, this motivation is both hilarious and terrifying in its banality.) Raimi’s film, however, is refashioned as a cartoonishly yucky morality tale that recalls the E.C. horror comics that were a natural American extension of James’s turn-of-the-century ghost stories.

The trials for Lohman’s Christine Brown begin after she refuses a foreclosure extension on the house of Mrs. Ganush (Lorna Raver), despite the elderly Roma woman begging on her knees to Christine at the bank. Angling for a promotion and a raise, and forced by her schmuck boss (David Paymer) to compete with asshole go-getter Stu (Reggie Lee) for the open assistant manager position, Christine claims to have been forced to have made this “hard decision.” Yet, as the film never lets us entirely forget, the choice to kick this woman out of her home was Christine’s. Our sympathies for Mrs. Ganush may become shaky once she turns demonic and violently attacks Christine in her car with a giddy, Looney Tunes abandon, then finally handing her a cursed button. Yet Drag Me to Hell works so well precisely because it constantly forces us to negotiate our sympathies with everyone on screen.

Christine is a slyly conceived main character. She’s relatable in her insecurities: her boyfriend (Justin Long) comes from a more privileged financial class; she struggles with body image. She’s “normal” in her work ambitions. She’s blonde and go-getting and well-mannered. Lohman elegantly uses all these seemingly untroubling traits to win us over. All of this makes it easier to justify Christine’s actions, but she’s finally an uncomfortable protagonist with which to identify. The first words Mrs. Ganush speaks in the film are “Will you help me?” For entirely selfish reasons, Christine’s response will be no. Whether this merits a violent earthbound haunting followed by eternal damnation in the pits of hell is up for (humorous) debate, but we don’t play by normal rules of logic when it comes to horror movie moralizing.

Drag Me to Hell is frighteningly engaging because of how it positions the viewer. We all make decisions, multiple times a day, that truly only benefit us and maintain the protective shield we have built around our lives. The unstoppable lamia that terrorizes Christine, and us alongside her, has ripped open the veil between this world and the next, exposing that protective shield for the thin layer of gossamer that it is. The curse is not a monster that disturbs the sleep of the innocent, but a palpable, touchable, snarling beast that reminds us of the fragility of our bodies and the consequences of our decisions. It’s there, lurking under the pillow, ready to bite when we least expect it. —Michael Koresky