Every Halloween, Reverse Shot presents a week’s worth of perfect holiday recommendations. Read past incarnations in our series “A Few Great Pumpkins.”

First Night:

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair

In his disquieting 1941 short story “Smoke Ghost,” influential horror and science-fiction writer Fritz Leiber asked if the traditions of the genre he was working in were no longer enough for the modern world. Its haunted protagonist, a city-dwelling advertising agency exec, has begun to see formless, soot-covered, malignant wraiths moving about the rooftops of buildings while commuting home on the elevated train. Looking out his office window, he muses vacantly to his secretary:

“Have you ever thought what a ghost of our times would look like, Miss Millick? Just picture it. A smoky composite face with the hungry anxiety of the unemployed, the neurotic restlessness of the person without purpose, the jerky tension of the high-pressure metropolitan worker, the sullen resentment of the striker, the callous viciousness of the strike breaker, the aggressive whine of the panhandler, the inhibited terror of the bombed civilian, and a thousand other twisted emotional patterns? Each one overlying and yet blending with the other, like a pile of semitransparent masks.”

Horror cinema has yet to catch up with the power of this image (written on the cusp of a world war) or to really engage with the idea that modernity itself has produced horrors so extreme that they would transform the being, the feeling, the bearing, and manifestations of our ghosts into something even more inchoate. Leiber’s febrile description is simultaneously too much and not enough, an acknowledgment of the impossibility of defining the growing terror of despair. What is our “smoky, composite face” today? Where are the filmmakers who are trying to show us our “twisted emotional patterns”?

Perhaps it’s time we had a little reckoning with horror. Can’t we safely make the statement, without gesturing to provocation, that by 2022 horror as a strict genre—as a series of mannerisms, motifs, and recurring legends—isn’t sufficient in reflecting the fears of our lost world?

At the time of this writing, horror is being hailed as cinema’s savior, with journalists pointing to the proliferation of horror hits at the box office this year, only a few of which are part of existing franchises. With pundits and prognosticators naturally using the genre to reclaim an industry still desperate to rebound from the pandemic and the slow death of streaming, one can understand the excitement. So expect a lot more of it—and also a lot more online bloviation and mouth-frothing about things like Halloween Ends, a film that, however much passion it would seem to engender in social media arguers, will be forgotten before All Saints’ Day.

While I love the queasy flipflop of the stomach, the momentary hair-raise, and the spasmodic moralism of the traditional horror movie, what we’re living through now seems to beg for a different kind of horror, and lately this has been best conveyed through hybrid genre forms. The past year alone has seen the releases or premieres of horror-adjacent films that overturn expectations without sacrificing dread. Only one of these, Jordan Peele’s expansive Nope—whose pop-genre savvy and sly Hollywood reflexivity didn’t prepare me for its genuinely disturbing images—has been a genuine hit. There are an exciting array of other films that refuse to fit within easy categories but play with horror conventions in thrillingly subtle ways. To name just a few: Joanna Hogg’s The Eternal Daughter, which lends the maternal melodrama the rhythms of a ghost story by M.R. James; Romanian director Radu Muntean’s woodsy Intregalde, which teases the viewer with the expectations of a city-folk-vs.-country-people thriller to ask questions about the limits of Samaritanism; Mark Jenkin’s maddeningly structural Enys Men, which is or isn’t some form of folk horror; Mexican-Bolivian filmmaker Natalia López Gallardo’s Robe of Gems, a nightmarish plunge into pure evil in the form of a missing persons case; and even Laura Citarella’s four-hour Trenque Lauquen, the second half of which allows for the possibility of a supernatural horror so offbeat that we’ll never know if it was there at all. Even less overall successful films (to these eyes) like Nanny, Bones and All, and Coma are messing around with the DNA of horror in effective, undismissable ways.

I’ve conversationally described many of these as “not really horror”—a provocative ambiguity. Perhaps the recent film that feels most productively and excitingly “not really horror” while existing squarely in the world of horror is Jane Schoenbrun’s nocturnal We’re All Going to the World’s Fair. Too singular an emotional and aesthetic immersion to function as a true indication of where the genre might go, Schoenbrun’s film works with its own exceptional internal logic, using the trappings of horror to productively upend expectations while also imbuing viewers with the feeling that the genre intends to create. We’re All Going to the World’s Fair may not be a horror movie as we’ve come to understand it, yet it’s undeniably a movie about the experience of horror—as aspiration, as escape, as void.

This is all fragilely embodied by Anna Cobb, whose disaffected teen Casey, like the film she carries, refuses to be easily defined. Even though we see her on-screen for much of the film, frequently in intense close-up as she looks directly into the lens (mimicking a webcam), we know very little about her: she appears to live in some bleak Northeastern nowheresville with a single father we never meet. We don’t see her in school. We don’t see her interact with anyone offline. We do know, from the extended, static opening shot, that she has decided to “take the World’s Fair Challenge,” a cryptic, barely explicated role-playing horror game that requires a kind of blood oath from its participants. For the remainder of the film, we’re left to wonder how aware or complicit she is in her apparent spiraling out of control.

There are multiple ways to read the film: a) Casey has been plunged into an actual nightmare, in which the World’s Fair Challenge genuinely deranges and transforms its players (as shown in a series of alternately goofy and unsettling testimonial videos—the closest the film comes to traditional horror), and therefore the film exists in a supernatural realm; b) Casey is losing her mind and sense of autonomy, even if the game itself is a hoax, and therefore the film exists in a psychological, still potentially surrealist realm; c) Casey is fully aware that she is part of a game and is purposely exaggerating her own emotional responses and reactions as a way of feeling connected to this alternate reality, and therefore the film exists in a purely realist dramatic realm. None of these scenarios makes the film any less compelling, and any of them portray Casey as a figure of enormous poignancy: an individual seeking transformation or maybe even transcendence.

Complicating—and enriching—matters is that our perspective is being uncomfortably mirrored by a secondary protagonist: a middle-aged (perhaps married) suburban man, who goes by the handle JLB and is known only to Casey via a gothic, hideously grinning ghost avatar, and who has begun contacting Casey. JLB claims to be concerned for her well-being as the game has continued and she has uploaded increasingly unhinged videos. But just like Casey’s complicity in the game (it’s either controlling her or is she a perfect practitioner of it), JLB’s motivations are ambiguous: is he a creep or a savior—or both?

Schoenbrun seems far too curious about the complexities of human beings to simply judge these characters; the lack of moralizing here is another feature that cleanly separates the film from traditional horror. We’re not in the realm of, say, desktop horror breakthrough Unfriended, in which a group of “very online” teen friends are terrorized by the ghost of a fatally bullied schoolmate. In the potent final scene of World’s Fair, Schoenbrun allows JLB a monologue that further blurs the lines of the film’s precarious tether to “lived” experience. What are the parameters of these two characters’ respective realities? Each craves catharsis, and they both invent stories to make them feel better about living in a world that increasingly encourages isolation.

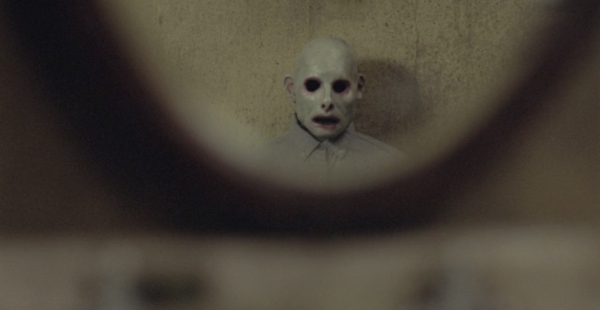

I think there’s something embryonic about what We’re All Going to the World’s Fair is doing with horror. Its influence might not be felt for years, even generations. Or it might be a supernal one-off. Schoenbrun allows the genre to take a new form, and this is best expressed perhaps by the surprising and constant adaptability of a visual aesthetic that might have seemed limited. Their single takes are sinister, dazzling, yet somehow never showy, especially the long mid-film shot that starts on Casey in bed and then follows her (as she follows herself) from the starry-night warmth of her attic bedroom to the forbidding backyard shed where she attempts to fall asleep to the sorcery of a projected ASMR YouTube video. Before she can drift off, she is interrupted by a warning from JLB: an image of her own face writ large, hollowed out, her eyes black sockets, her face distended and gaping like a childhood nightmare, her own visage turned into a kind of creepypasta warning to the curious. To return to Fritz Leiber, have you ever thought what a ghost of our times would look like? Just picture it. —Michael Koresky

Second Night:

The Funhouse

When Mel Brooks burlesqued Psycho’s shower scene in his grinning Hitchcock tribute High Anxiety (1977), he used a rolled-up newspaper as an absurdist substitute for a kitchen knife. Four years later, in the prologue to The Funhouse, Tobe Hooper—at that point, not a filmmaker known for his sense of humor, having signed The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Eaten Alive, and Salem’s Lot—got better comic mileage out of a wobbly rubber prop blade, wielded by a preadolescent slasher fan against his naked (and suitably apoplectic) older sister (Elizabeth Berridge), whose terrified reaction he photographs simultaneously. You know, as a goof.

Besides tidily satirizing the incestuous—and scopophilic—subtext burbling beneath his contemporary John Carpenter’s hit Halloween, Hooper’s wicked POV sight gag sets up the tricky dialectic between illusion and authenticity that runs throughout his third feature. Like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Funhouse is, at its core, a story of bored and callow teenagers who go looking for fun in the wrong place at the wrong time. But where its predecessor unfolds as a rueful, period-specific allegory about a divided America—an unsentimental story of city hipsters sacrificed on the altar of their own condescension—the follow-up exults gloriously in the irony of thrill-seekers getting exactly what they paid for. Their comeuppance comes with the price of admission.

Always a patient filmmaker (which makes his predilection for hairpin tonal and narrative turns all the more effective), Hooper takes his time switching gears from spoof-mode to all-out horror. After loudly vowing to get revenge on her sibling for his prank, Berridge’s Amy exercises her young-adult privilege by skulking off into the night against her parents’ wishes, leaving little Joey (Shawn Carson) to bide his time with The Bride of Frankenstein on television. Her non-approved chaperones for a jaunt to a sleazy local carnival are her dumbass boyfriend Buzz (Cooper Huckabee), his even dumber-ass pal Richie (Miles Chapin), and Richie’s slumming girlfriend Liz (Largo Woodruff)—a motley crew whose gawking, gimlet-eyed contempt for the proceedings get reflected back at them by the carnies who view them as easy marks (or fresh meat). In 1975’s little-seen and experimental The Amusement Park, George A. Romero styled a small-town fair as a kind of metaphorical purgatory for abused senior citizens. Hooper’s presentation is more anthropological, immersing us in the carnival’s rituals and imagery via gorgeous, mobile camerawork by Andrew Laszlo, who shot Walter Hill’s The Warriors, until we feel like we could navigate its winding, nightmare alleys along with the characters.

Ambience is one of Hooper’s specialties, and the atmosphere in The Funhouse (and the fun house) is laid on exactly as thick as any ticket-buying, liquored-up, hoping-to-get-lucky interloper would hope, smoky and loud and streaked with lurid, delirious patterns of paint and colored lights. The same prurient showmanship that initially enraptures Amy and her gang as they make their way between booths featuring strippers, sideshow attractions, and fortune tellers (with the great Sylvia Miles hamming it up as the mystical prophesier Zena) is what paralyzes them when, hanging around the grounds after hours, they witness what looks like a mercenary sexual transaction between two carnival workers gone wrong. From their hidden vantage, it appears that Zena has been killed by a ride assistant wearing a Frankenstein mask; as the film goes on, they—and we—become privy to the hulking figure’s real, hidden identity and monstrous physiognomy.

Sharp-toothed, red-eyed, and monstrously disfigured beneath stringy white hair, the cartoonishly monikered Gunther Twibunt (Wayne Doda) is the biological son of the reigning (and corrupt) freak show barker Conrad (Kevin Conway). And, as his Boris Karloff drag suggests, he is—like Gunnar Hansen’s Leatherface— also a purely symbolic sort of progeny. Lurching around in the dark in pursuit of the intruders who’ve ripped off his father’s safe and witnessed his own unspeakable crimes, he’s a fearsome yet weirdly touching embodiment of a carnival’s historical, immutable rule of inversion, in which the repressed is not only coaxed out and celebrated but also imbued, at least for the night, with a ruling, (im)moral authority.

The Funhouse was written by Lawrence J. Block, a longtime friend of Stan Lee who later contributed material to Albert Pyun’s producer-massacred adaptation of Captain America. The script was purchased by Universal in an attempt to cash in on the success of Friday the 13th, which contextualizes both the sly, genre-savvy satire of the opening sequence and the gory, blunt-force violence of the final act, which is similarly booby-trapped against itself as farce—slipshod, haphazard, and conspicuously unsatisfying, even and perhaps especially when Gunther finally gets his. One doesn’t have to infer (or project) any overtly self-reflexive agenda onto Block or Hooper to see The Funhouse as a movie that reflects certain market conditions without wholly capitulating to them, but the evidence is there; in his 2021 Hooper critical study Cinemaphagy, Scout Tafoya suggests that willful deconstruction was indeed a part of the director’s project. “You won’t find a more succinct deconstruction of the Freudian and grammatical underpinnings of the slasher movie,” he writes of The Funhouse. “Hooper had a little distance from the subject and used it to his advantage.”

The idea that two-bit huckster Conrad is also a sociopath exploiting his blood relations along with all the other geeks in his employ bristles with a nicely cynical, no-biz-like-showbiz subtext. Crucially, when, in the final shot, a bruised and battered Amy emerges from the carnage to greet the dawn, the graceful, purposeful arc of the camera is more interested in the sprawl of the grounds themselves, which bear traces of the after-hours psychodrama but remain in working order. If the animatronic fat lady mounted on the entrance isn’t singing, she’s still grinning, from here to eternity; Hooper’s movie is over, but the show must go on. —Adam Nayman

Third Night:

Ginger Snaps

Ginger Snaps has an autumnal, suburban flair, made all the more vivid by the windswept haze of its pre-digital palette. In this Canadian film from 2000, directed by John Fawcett and co-written by Fawcett and Karen Walton, the texture of the film’s footage is primed for the kind of “flash-negative with a thunder sound effect” trailer that filled the first ten minutes of many seasonally reissued VHS tapes. It’s a creature feature for teen girls, with purple serums in vials and nasty, rubbery gore and snide juvenile banter and an ear for a now-extinct strain of youthful vernacular. The high schoolers of this world mosey about, tug at their mismatched layers of clothing, fake their own deaths in squib-and-paper-mâché tableaux spurred on by irony-poisoned suicidal ideation. The entire movie is imbued with a delightful naiveté that has made it a canonical object of nostalgia for many.

It is surprising, then, that Ginger Snaps remains so upsetting. The movie is enamored of its own harshness. Every rewatch uncovers different, unsuspecting phrases to terrorize the nervous system anew. In the opening scene, Ginger (Katharine Isabelle) waggles her hand to her sister Brigitte (Emily Perkins) in search of blithe reassurance. She repeats the mantra they’ve maintained since they were children: “Out by 16 or dead on the scene, but together forever.” The camera holds on her palms in a shot from Brigitte’s POV, the focus so shallow you can’t even make out her fingers or forearm.

The plot of the movie is simple enough that it could take place on Fear Street. Ginger and Brigitte are teenage girls obsessed with death. Ginger gets her period and is bitten by a werewolf. She lures boys to the slaughter under the false promise of sex. Brigitte, realizing what is happening, searches for an antidote.

Ginger Snaps is exhilarating in how it runs its metaphor, Gump-style, past the touchdown line and out into the parking lot. What begins as a bloody double entendre for a teen girl’s horror at puberty and sexuality quickly devolves into madness, a startling evocation of the destruction left by rape across the bodies of young girls. Yet instead of merely settling for such rich material, the film’s eye shifts away from Ginger towards Brigitte. Armed with a newly unearthed conception of sexuality, Brigitte is forced to acknowledge herself as a victim of lifelong filial abuse. During their last conversation, a crazed Ginger shrieks, “I said I’d die for you.” Brigitte hurls back, shaking, “No, you said you’d die with me. Cause you had nothing better to do.”

Every viewing reveals further troubling dimensions of their relationship: the mother’s resentment for their closeness, the claustrophobic basement where they sleep, the way each seems to be circling towards the other at the schoolyard even when the audience can’t see them both. The incestual tenor of their relationship is never made textual, instead contributing an aura of intimate malice. Ginger Snaps circumvents the strained paint-by-numbers allegory that befalls so many thematically similar horror flicks by playing out its conceit to its schlocky extreme. Ginger the werewolf is not a metaphor but a catalyst for latent tensions.

Walton and Fawcett’s screenplay demonstrates care in its writing of young women, especially noteworthy in a genre where pubescent femininity is so often the progenitor of evil. Ginger Snaps understands that sexual agency does not preclude predation, that no familial relationship can be boiled down to a single vector of attachment. Brigitte and Ginger role-play and persona-swap as each other’s captors, parents, domestic partners, rivals, scapegoats. Every corner of Ginger Snaps is infested with rotten, PTSD-fueled cruelty and emotional warfare.

In the film’s final moments, Brigitte collapses in exhaustion atop her sister, now unrecognizable after her lycanthropic transformation, their bodies sandwiched haphazardly on the floor between their matching twin beds. The power of Ginger Snaps comes from its ability to pinpoint the genesis of childhood nostalgia while also holding its unwavering gaze on the moment that illusion is shattered. It is a movie that’s less about losing the safety of girlhood than discovering you were never safe to begin with. —Sam Bodrojan

Fourth Night:

Frenzy

“Every cloud has a silver lining.” Within the first ten minutes of Frenzy, Alfred Hitchcock has laced this banal phrase with poison. These words are spoken by a lawyer who’s ambled into a Covent Garden pub for lunch with his friend, a doctor. After ordering shepherd’s pies and pints, they speculate on the motives behind a recent string of killings by “the necktie killer.” The bartender, wild-eyed, leans in to tell them: “I hear he rapes them first.” The two men share a smug laugh, and one of them replies…

To be sure, Frenzy offers up several disquieting, dreamlike visuals: a nude corpse washing up on the edge of the Thames; a torrent of potatoes, loosened from a sack concealing a body, tumbling from the back of a truck by night; the gleam of life draining from a victim’s eyes in extreme close-up. But its horror also lives in the breathing room between murders, which is suffused in atmospheric queasiness. The film’s logline may suggest a killer in the vein of Jack the Ripper or Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), but Hitchcock wrests his London Gothic murder plot out of the nighttime shadows and into the bustling everyday. Cinematographer Gilbert Taylor, drawing inspiration from The French Connection’s perspective on Brooklyn, plainly films the daily grind of Covent Garden’s produce markets and taverns, the flow of workers, shoppers, drinkers. After a power clash directing Paul Newman in Torn Curtain (1966), Hitchcock opted to cast London stage actors, and their relative anonymity proved an asset. The film’s quotidian New Hollywood grit brushes awkwardly against Hitchcock’s ingrained classicism; this tension alchemizes Frenzy’s brand of nausea. What otherwise might have been repressed or coded can now be expressed directly, like a blocked sink tap spurting and spraying erratically—in straightforward depictions of sexual violence, as well as in the cavalier asides of secondary characters.

As we might expect, the film plays with Hitchcockian “wrong man” expectations. After the aforementioned nude corpse washes up on the edge of the Thames—Hitchcock cameos as a bystander who can’t look away, distracted from a politician’s speech about heavy Thames pollution—we hang tight to a typical day in the life of Richard Blaney (Jon Finch). He’s a flimsy excuse for a “protagonist,” let alone an anchor character. Blaney is a troubled former RAF pilot with a drinking problem, a consistent mess in romantic and professional settings. His temperament also runs quite hot—during one tense conversation in a restaurant with his ex-wife Brenda (Barbara Leigh-Hunt), he crushes a brandy glass into shards with his bare hand. Instead of Cary Grant or James Stewart, Hitchcock straps us in sidecar with a diet cola version of Oliver Reed. And by 1972, the Master of Suspense knows this is way too easy—we’ve internalized typical Hitchcockian misdirection. So, Frenzy lays it on thick, as though that framework could only be a joke: during the “silver lining” pub chat, Blaney occupies the right half of the frame, and his purple necktie is so bright as to be unmissable. In fact, his character is first introduced while tying his tie.

All this scene-setting is an ironic, meta form of misdirection. For the opening titles, Hitchcock fired the film’s initial composer—none other than Henry Mancini—after he submitted an eerie overture with church organs. After that, Hitchcock hired Ron Goodwin and saddled him with an extremely detailed commission for classical-style fanfare, which has approximately as much character as stock music. This score invites us into a space that characters wish were ruled by easy, outdated movie-world moralism. Almost every secondary character wants to be the one to turn Blaney into the police—and he is charmless enough that he wouldn’t be able to shake them off with a Hitchcock-hero card. But there are deeper problems in this repressed, alienated city; all “functional” domestic partnerships seem impossible to reconcile, sexually stilted, or just plain bizarre. The chief Scotland Yard inspector (Alec McCowen) frequently discusses the murder case’s gory details over enormous platefuls of English Breakfast—or while picking at the overcooked gourmet dinners prepared by his wife (Vivien Merchant, possibly the film’s MVP), who’s enrolled in a cooking class. At one point, they snap excitedly into dry breadsticks while speculating on how the killer might have extracted a tie clip from the hand of a corpse in rigor mortis; they approach it like a parlor game. (The libidinal link between sex, food, and murder is, again, laid on thick.)

When the expected bait-and-switch happens—toward Blaney’s friend Robert Rusk (Barry Foster), the amiable proprietor of a produce market—Frenzy’s violence is made even more disturbing by this atmosphere. As Londoners gossip about the killings, there seems to be very little concern for the victims, only a detached attempt to understand the psychopathy of the murderer. Women are “asking for it,” most men “don’t look like the type”—though, how is it possible not to look like the type when these cinematic serial murderers are always hiding in plain sight, maintaining a clean-cut surface? The pivotal, extremely harsh murder of Brenda is an update of the Psycho shower montage, but devoid of the musicality that triggered quickened pulses. Instead, Frenzy is designed to make the viewer feel unclean, unpleasant, somewhere closer to complicit. The sequence is brightly lit, maintaining tight framings but slowing the pace, lingering on the whites of Brenda’s eyes as Rusk holds her down. There is no music, only Brenda hauntingly reciting a Bible verse while Rusk grunts “lovely” over and over. And the only nudity in the scene, a breast in profile, is framed so as to feel like a violation, then hastily, insufficiently covered up.

After this sequence, we never see Rusk kill again, but the memory is enough. When Rusk escorts another victim, Blaney’s girlfriend Babs (Anna Massey), to his apartment, the camera trails him up the staircase. When he tells her, “You’re my type of woman,” the door to his flat clicks shut behind them; this line was the beginning of the end for Brenda, and the writing is on the wall. Hitchcock’s camera, now untethered to anyone’s point of view, tracks slowly backwards down the vacated staircase, then out the front door of Rusk’s building. It’s a typical London day outside, and the flat’s façade is another deceptively ordinary surface. We can only passively watch. —Chloe Lizotte

Fifth Night:

Maniac

On the poster for William Lustig’s Maniac (1980), a faceless brute is seen brandishing a bloody knife in one hand and the scalp of a blonde woman in the other. Dripping from her hair, a pool of blood has puddled around his dirty white sneakers, and the words “I WARNED YOU NOT TO GO OUT TONIGHT” are seen in bold capital letters. It is a warning, and it did the film no favors with critics. Gene Siskel was so offended by Maniac that he took to his local news affiliate in Chicago to protest the opening of the film in his city. He decried the existence of slasher films, lumping them all together as “essentially the same movie,” and he argued they were a reaction to the social gains women had experienced in the 1970s. Siskel is correct in his estimation that Maniac is misogynist, but misogyny can be worthwhile in a horror film if there is something real to be extracted from its representation. In Maniac, the violence on display is vivid and uncomfortable, and reflects the ambient mortal dread of being a woman alone at night.

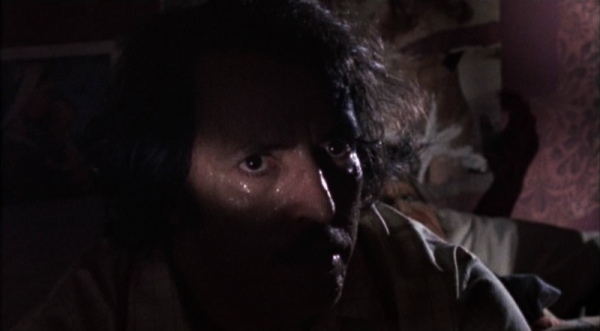

Maniac is one of the more troubling and complicated horror films of its era, because it forces the audience to stew in the sickness and self-hatred of its serial killer Frank Zito (played by the great character actor Joe Spinell).It is not a seductive exercise: it is almost completely lacking in sex, and there’s no sense of beauty in the camerawork, as there was in John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). Maniac is a dirty picture that lurks in the damp, unwashed corners of Koch-era New York City. The cinematography by Robert Lindsay is fixated on darkness and is akin to Gordon Willis’s technique in Klute. Maniac shares the same leering, uncomfortable qualities, but unlike Klute, our perspective isn’t aligned with the woman being watched, but rather the man in pursuit. C.A. Rosenberg’s screenplay, co-written by Spinell, is almost totally bereft of dialogue, which gives Lustig the opportunity to play around with the visual grammar. He creates a violence through Zito that is intimate with close-ups and over the shoulder tracking shots. Zito’s first kill is reminiscent of the Zodiac killer’s picnic murders in David Fincher’s 2007 masterpiece, but here, it serves as character introduction. The following murders carry greater thematic weight, such as the strangulation of a nameless sex-worker (Rita Montone) in a roach motel. During the murder, Lustig’s camera is looking directly up at Zito in a point-of-view shot that captures his unblinking, possessed eyes. We share the final image that this girl will ever see as she lies flat on her back on an uncomfortable hotel bed as her life leaves her. The shot selection brings the audience uncomfortably close to the action, and it’s as though Zito has wrapped his large hands around the neck of the camera to kill us all.

Maniac says something intelligent and worthwhile about misogyny and violence through precise visual composition, and the framing and editing robs the bloodshed of any satisfactory release. The great practical effects wizard Tom Savini handled the gore in Maniac, but none of it has the same cackling guffaw of extravagance one might find in his other work, such as Dawn of the Dead. It is matter of fact, and he says it was inspired by his time serving as a combat photographer during the war in Vietnam. Savini even plays a random victim whose head is blown off with a shotgun blast in slow-motion, but the way Lustig constructs the scene negates the potential for excitement. He ends the encounter with a close-up of the barrel followed by a long still shot of Zito with his back turned to the camera sitting in his lonely apartment. It is not a grand spectacle of violence, because we are forced to focus on the affliction experienced by one man trapped in the spider web of his own mental deficiencies and habits of destruction.

Frank Zito was conceived as an amalgam of real-life murderers, and Spinell’s performance oozes despair. He is not charismatic, nor does he have a philosophy of why he’s killing, like so many on-screen murderers. Killing doesn’t make him happy, and the sexual release he gets is only momentary, and complicated by problems he has with his own gender. The immediate, obvious comparison is with Ed Gein, whose obsession with mutilating women and making their corpses into clothing and household objects inspired a pattern of on-screen murders dating back to Norman Bates in Psycho, and continuing through Leatherface in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs. When he is introduced, we see him prodding at his breast in the mirror and he is evidently unsatisfied with what he sees. It suggests gender dysphoria, but that’s as far as the characterization goes. Far worse are his Freudian troubles with his mother and the resulting effect his upbringing has had on his life. He mumbles “mother” to himself while killing, suggesting some catastrophic mystery of childhood never revealed. Zito has mannequins scattered about his lavender-painted bedroom, and he is fixated on taking care of the scalps from his victims that he has placed atop their heads. He brushes them gently, trying to make them “pretty.” But he is not proud of his trophies; rather, he feels shamed by them, and seems embarrassed by his own actions, like a teenage boy caught masturbating by his parents.

Zito’s crimes are all over the headlines of local newspapers, reminiscent of the Son of Sam period in New York City. His murders have become small talk, and there is a tension in the air that anyone could be next. Lustig best dramatizes this in a scene in which a nurse (Kelly Piper) is stalked in a quiet subway station. The nurse has no indication that she is being followed, but upon spotting Zito a couple hundred feet behind her she quickens her pace. Lustig cuts between her frantic face and Zito’s plodding feet in close-up. Women understand this fear intellectually and emotionally. We’ve been warned of it since adolescence, and here it is evoked perfectly through two shots. She sprints to the first subway station she can find, but no one is there to stop her would-be killer. She scuttles off to a stall in the women’s bathroom to hide, and Lustig positions his camera uncomfortably close as she heaves with dread, struggling to breathe. She is filmed from the neck up with the frame tilting to the ceiling and it makes her stretched face appear almost alien with fear. This is the only kill where the perspective breaks completely from Zito to the victim, and the audience is made to feel everything she feels as she waits for an opportunity escape, which makes it all the more harrowing and despairing when Zito finally catches her. In the following scene, Zito is seen taking her removed scalp and placing it atop a mannequin in his bedroom, completing the nurse’s transformation from person to object. —Willow Catelyn Maclay

Sixth Night:

Baby Blood

Few contemporary horror films begin as grandly as Alain Robak’s 1990 French curiosity Baby Blood. A gory B-movie that sets out to detail the evolving, murderous relationship between a womb-dwelling invasive parasite and the woman who reluctantly carries it to term is under no obligation to begin at the literal formation of the Earth. And yet, following Robak’s dip into the primordial soup, envisioned via stock shots of splashing volcanic lava paired with the voiceover of the parasite (Robak himself, heavily detuned and distorted), explaining its origins and ultimate desire to be born, it’s easy to question why more horror films don’t shoot similarly for the moon. Wonder at the filmmaker’s audacity and/or insanity might continue into the first post-title sequence, set in an unnamed African country, and in which the liberal use of wagging POV shots from inside a cage suggests something bad, some evil force, is now on the move. Plenty of screen time elapses before we have any idea what at all is happening.

The cage turns up, some weeks later (time is marked via endearingly silly text cards), in the North of France. It has conveyed an upset jungle cat to a desultory circus that’s clearly on its last legs, wasting away in country that looks not unlike the stomping ground of Bruno Dumont in La vie de Jésus and L’humanité. The troupe is bored stiff between performances, their premiere cats won’t obey, and voluptuous, gap-toothed Yanka (Emmanuelle Escourrou)—a feline tamer in training and the abused moll of the group’s tyrannical leader—is looking for any way out. It’s certainly not a good omen when the new arrival literally explodes in its cage a few days after arrival. Robak provides this revelation with a perfect comedic grace note that suggests the film’s modus operandi: a tuft of white fur floats slowly to the ground amidst the splatter of bright red gore.

It seems the cat was merely the latest carrier of the sentient wormlike parasite we last met at the beginning of time. The now-freed creature doesn’t take long to take up residence in Yanka’s womb, where it stays for the rest of the film, waiting to be born into something. In an unexpected move, the growing fetus maintains a running, guttural dialogue with Yanka that is by turns combative, imperious, pleading, curious, and sweet. As the pair flee the circus and Yanka takes up odd jobs to make ends meet, the film at times suggests a blood-soaked, pre-natal Look Who’s Talking, even dipping into broad comedy in scenes where Yanka answers the voice in her head leading to the surprised confusion of the human being standing in front of her. Yes, the creature pushes Yanka to murder on the regular and drink the blood of her victims to help further its own development. Yes, it does threaten to explode her stomach if she disobeys. But it also asks her about her taste in men, about her becoming a mother, about her feelings in general, if she’ll miss it when it is born. In a world in which all human interest in Yanka we see is sexual, this relationship with the voice inside her is the most sympathetic she has.

My general dislike of the films of Jacques Audiard tempts me to label the film’s choice to cast him as an unnamed jogger who gets run down and decapitated by a car as its greatest gift to the cinema, but that would be highly unfair to a movie that comes bearing myriad, needless delights. In addition to the symphonic opening, there is the way the script continually turns over and deepens the relationship between Yanka and child; in a similar way that Rosemary’s Baby is one of the cinema’s great pregnancy culture satires, Baby Blood manages to etch similar doses of realism amongst its absurdist flights. How many mothers to be haven’t looked at their swollen bellies and felt frustration at the unknown thing feeding off their life?

But it’s also worth mentioning Robak’s shot-making, which is often ingenious, his camera placed at odd angles to the action, capturing detailed choreography in complicated long takes. Note should be given to the director’s impressive control of tone and easy ability to switch modes on a dime: a gory groan-inducing image might give way to a laugh-out-loud funny sequence satirizing early ’90s French consumerism, which might abut a swooningly romantic take of Yanka considering all that has befallen her which might not be out of place in Jean Rollin. Baby Blood is one of those kitchen-sink oddities in which it seems everything is on the table and nothing makes sense but everything somehow just works

I’ll be forever grateful to Asha Phelps, my partner in crime and, shortly, parenthood, for digging this one up for inclusion in her recent “Pregnant with Fear” series which ran, for nine (naturally) weeks at the IFC Center recently this summer and fall. It’s not only a worthy addition to the small but vital corpus of pregnancy horror films but also the kind of discovery that we keep coming back to this odd and strange genre to find. It might also be a key to understanding French horror in general, situated well before the onset of the New French Extremity (a sequel, Lady Blood, also featuring Escourrou landed right in this midst of that early aughts moment); one wonders if Baby Blood was seminal in birthing an entire movement. —Jeff Reichert

Seventh Night:

Possum

In Trevor Griffiths’s 1975 play Comedians, a group of aspiring young northern English comics audition for a top talent agent from London. The most gifted and brilliant amongst them, Gethin (a role originated by Jonathan Pryce) delivers, at the play’s climax, a 20-minute set brimming with violence, class hatred, and despair, which his bewildered teacher condemns as “terrifying” and devoid of compassion and truth. Gethin protests that on the contrary, it is “his truth”; the play entreats comedians to explore the certainties of their own existence on stage, no matter what darkness lies within. Matthew Holness, the director of the uniquely and unreservedly bleak 2018 British horror film Possum, is a comedian. His protagonist, Philip (Sean Harris), is a puppeteer. While we never see Philip’s act, we do, by increments, discover the puppet itself. And the film leaves us in no doubt that the performance must be borderline unwatchable. Philip’s Wite-Out countenance and rictus grimace endure for most of the film’s 80-minute run time. He is not so much haunted as in a state of perpetual, agonizing trauma.

In returning to his childhood home in the Fens, one of the most nondescript parts of England imaginable (between Cambridge and…nothing) Philip is trying to escape his past. His monstrous spider-limbed puppet, Possum, is kept in a leather bag which Philip carries everywhere like a cross. Philip will spend the film trying to escape Possum, too. All at first is ominous allusion: Philip’s world (and that of the audience) is bestrewn with elliptical fragments of visions, snatches of a children’s poem, figurative flashbacks (party balloons engulfed and defaced by black smoke), and muted behavioral detail. He sees schoolboys on a train and for one sickening moment, his permanent scowl melts into an expression of affection. A TV news report emerges later about a missing teenager. We aren’t told anything, but we join all the dots.

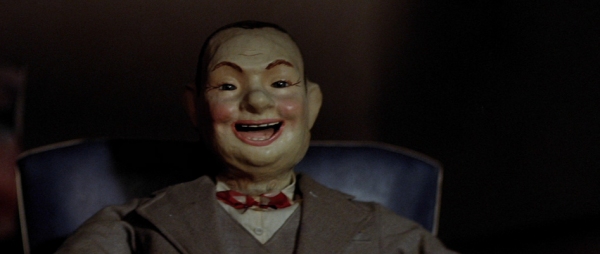

On arrival, Philip meets another puppeteer, retired, his uncle Maurice (Alun Armstrong). This wizened, splenetic old man is a comforter-tormentor, like Shakespeare’s Iago, or Scorsese’s Judas. Maurice barely conceals his sadistic contempt for Philip, beneath terms of empty endearment: “it’s all right, boy” he prods at Philip’s yawning wounds, while Philip attempts to exorcise whatever ghastly events took place years before, via the disposal, by any means possible—drowning, fire—of his hideous, Chelicerata-like creation. But Possum won’t go quietly: this puppet, evidently created for catharsis but now a psychological millstone, continues to terrorize Philip by appearing in his room, in his bed when he wakes. Beyond the unignorable allusion to Cavalcanti’s ventriloquist section of Dead of Night (1945), this form of intimidation (of Philip and us) is a staple of all horror, ancient and modern, from Paul Wegener’s The Golem (1920) to The Babadook (2014) and it taps into Ernst Jentsch and Sigmund Freud’s theories of the Uncanny, which explore the fear metrics of dolls and puppets come to life, as per Poltergeist (1982) and Child’s Play (1988).

But while there is plenty that is classical about Holness’s film (at 1:02:16 is an image of quiet, sublime classicism: a most exquisitely judged visual evocation of Halloween’s Michael Myers), the look and feel are wholly distinct from any of the above. Using desolate, washed-out Fenland locations ingeniously shot by Kit Fraser on 35mm film and with a music score by the Radiophonic Workshop—a sound department of the BBC which developed into a crucible of experimental music—Possum captures and repurposes the aesthetics of the short films produced in the 1970s and ’80s by the British Government’s Central Office of Information, warning Britain’s children of the dangers of their world, such as farm machinery, pedophiles and playing too close to railway lines (respectively: Apaches, Never Go With Strangers, The Finishing Line). These short films were so explicit and harrowing, featuring as they did children being mangled and eviscerated, that to young Britons they took on a psychological dimension akin to what Heinrich Hoffman’s barbarous cautionary tales did to German kinder.

Within this hostile environment, the discomfort and suspense grow like fungus, from the terrible mystery of Philip’s past sins to the nature of his impending penance: ultra-brief snatches of action wherein Possum appears to be alive and mobile—sequences cut almost immediately after they begin—freeze the blood. Holness toys with us, such as when Philip bundles Possum into an oil barrel, ready to burn him: is he moving the legs, or are they moving of their own accord?

This terrifying ambiguity underlines the film’s commitment to evoking the Uncanny, creating an unconscious reminder of Philip’s own id through the abomination he has made and tried to conceal. By aligning itself so closely to a text that foretells the tropes of the entire genre, there is an appealing academic purity to Possum. And yet…Philip’s story is resolved by a complete puncturing of its Freudian dimension. The film concludes, in a cruel climax of disarming clarity, with banality and squalor. Never mind the dreams and spiders, the real world—as we all now know—will always be more horrifying. —Julien Allen