The Goods:

The Multi-Platform Multiverse of El Planeta Director Amalia Ulman

By Chloe Lizotte

“With eyes wide open, I now stare at what was meant to be consumed in a state of blindness.” A soft voice recites this over a dull turquoise presentation slide of two objects: a pair of underwear from London and a souvenir treasure chest from Spain. Despite their differences, they have identical prints—phrases written in a language that isn’t quite French (“Les Boeribles et efpouecq…” doesn’t translate to anything), typeset in layered serifs like mid-2000s Starbucks mugs.

These print-based linkages between disparate souvenir objects are the focus of Buyer Walker Rover (2013), one of several “performative lectures” by Amalia Ulman, the Argentina-born multimedia artist whose debut feature, El Planeta, releases theatrically this month and digitally in October. In this format, Ulman delivers a prepared speech over PowerPoints filled with kitsch templates and infographics. She whisks through ornate analyses of images that seem superficial, even defiantly nonsensical in the case of these fast-fashion prints. There’s a knowing humor to this, especially when the objects display this comically glitchy Lorem Ipsum placeholder text; one print reads in Comic Sans, “I Used Think. / I Had The Answeet / To Everythink. / The Dream is Sweet. / now, must buy item.” Yet Ulman nominates this soupy verbiage as the oft-overlooked language of consumerism: “On a reappearing type of design, like that of the fake newspaper, or the word collage, I can feel a repetitious and redundant form of creation close to that of the mandalas.” Because these items are everywhere, perhaps there’s something to be gleaned from their algorithmically generated gibberish, even if it’s withering away in an airport souvenir shop.

Ulman has described herself as an artist “based in airports”: functional travel hubs with a navigable universality, regardless of their actual location. Ulman is best known for multi-platform performances that encompass social media, installations, and even adjacent press coverage. The idea of being “based in airports” defies background context in a way that “New York–based,” her current status, would not. The location subliminally conjures up performance art-y lineages and also simplifies the global reality of her life, growing up mainly in Spain, attending Central Saint Martins in London, and spending much of her twenties in Los Angeles. The airport is also a class-prohibitive fact of making art in a gig economy. As the protagonist of El Planeta, Ulman plays a recent art-school graduate who is offered the chance to style a Christina Aguilera photo shoot “for exposure, ”but there’s no fee to offset the exorbitant price of a plane ticket from Spain to New York. In her own life, Ulman has described the need to scramble for travel funds when opportunities are dictated by international commissions, grants, and fellowships.

Ulman’s multimedia works deal with the relationship between public image and this inhospitable globalism. Her interest in souvenirs draws her to objects designed for mass consumption: later in BWR, she points to the “wavy willow” vase, ubiquitous in offices and hotels, as an object that transcends class by fading easily into the background. It’s also a decoration that no one would be excited to own because it’s so inoffensively generic. In her performances, Ulman wonders how these class-based cues might apply to virtual identity. Each post—the goods we purchase, the artists we support, the memes we share—adds to the subconscious haze of tastes that make up a digital persona. It’s not so simple to separate on- and off-line worlds anymore; seeking the center of a person even seems misguided when it’s all so muddled. On Ulman’s website, for example, a link to her CV is sandwiched between an aura report and a handwriting analysis, a light joke on the possibly futile pursuit of understanding her better. By pairing many of these performances with lectures, Ulman also suggests that any digital encounter with a person is an act of interpretation—which is, itself, a form of consumption.

***

The first performance that Ulman scripted on Instagram, Excellences & Perfections, took place in 2014. (Rhizome has archived all of her posts.) At the time, Ulman was intrigued by the early age of Instagram influencers, particularly the ritual of renting a room at a luxury hotel to take selfies: an obvious illusion of disposable wealth that, nevertheless, attracts followers and brand endorsements. So Ulman decided to undergo a multi-month transformation into one of these Instagrammers, a story told through thirst traps and staged plastic surgery. The narrative has three phases that unfold in distinct aesthetics. In the beginning, Ulman poses in angelically cutesy palettes of pale pink, lace, and flower petals. Then, she adopts an intense workout regimen alongside promotional posts for fragrances and lingerie. After a breakup, she starts sharing memes about losing trust in others, which grow more and more caustic—at one point, she takes a selfie while brandishing a gun—after which she writes an apology and feigns enlightenment. In her final form, she uploads trite curlicued aphorisms alongside pics of teatime meditations with her personal trainer, all between shopping trips.

The feed depicts one person’s materialism-induced breakdown and rebirth, mimicking the experience of scrolling to the end of someone’s profile, glued to their drama of reinvention. An impressive and very funny part of this is the way that Ulman self-brands in captions. In Ulman’s spacey “art girl” phase, she would place a corny line drawing of a book alongside the caption “whatss your fav book? i lov reading.” The words and image, superficial by design, have a subliminal impact: she is “The Girl Who Reads,” where reading becomes a generalized aesthetic choice. A specific note about a book or author may not have as wide of an appeal; the vagueness keeps the focus on the surrounding selfies. Similarly, a cheerful “Good morning! #happy #sunny #retro #vintage #cool #LA” will net Ulman followers through hashtags, all facsimiles of real-world ideas. Many of her captions immediately register as full-throttle trolling: consider the elegance of “Really really miss gavin [sic] a bathtub :_____( some 1 buy me one :( ” alongside a hazy picture of Ulman’s legs in the bath. Ulman’s very-online sense of irony underlines the impossibility of authenticity; could anyone be for real when they type something like this? The fact that 88,000 people followed Ulman’s account implies that authenticity is an outdated destination—that an Instagrammable “hot girl” is less real than an aesthetic idea, available to consume in your desired network of keywords.

Excellences and Perfections succeeds because it doesn’t condemn the emptiness of the influencer’s lifestyle. Instead, it magnifies the work—and, for the surgical procedures, the cashflow—required to become this person. During the second phase of the piece, Ulman’s bio warned users that she was both the “*Boss of Me*” and “Addicted to Sugar,” but maintaining an Instagram-ready body involved a stricter regimen; Ulman took rigorous pole-dancing classes, followed the Zao Dha diet, and used prosthetics to fake a breast augmentation. In her real life, Ulman has a permanent disability in her legs due to a bus accident; since she presents as able-bodied, she has written about the stigma and skepticism she encounters when asking for aid. She’s identified the need to mask any suffering as a symptom of capitalism, and Excellences & Perfections dramatizes how these dynamics are baked into—and exacerbated by—Instagram’s form. The “Amalia” of the piece buckles emotionally whenever she tries to suppress her own bodily labor: it may be the reason why people follow her, but only when she’s able to package it in a way that is non-threatening. When she peppers images of syringes or firearms into the grid, for instance, it’s a break from what her followers have come to expect—compelling her to backpedal and package these cries for help in a #relatable redemption arc.

Online scrutiny comes up differently in Ulman’s 2014 performative lecture, The Future Ahead, which focuses on Justin Bieber’s coming of age as a social media celebrity. In response to a cultural fixation with Bieber’s angelic looks as a child and a decrease in his relevance around puberty, Ulman proposes that when Bieber was around 17 he developed an expression called “Office Blind Pose,” wherein he raises his eyebrows so that his forehead resembles Venetian blinds. These wrinkles in his baby face project an air of maturity, which Ulman links to the social construction of masculinity, counteracting a crude meme at the time that Bieber was secretly a lesbian. The OBP strategy seems like a punchline until Ulman compiles a few dozen photos of Bieber making this face—which, it must be said, looks ridiculous—alongside clips of teen vloggers mimicking it themselves. Ulman shuffles through them one by one in a type of obsessive, tongue-in-cheek analysis not usually directed toward masculine-presenting cis men (recall the viral GIF of Paris Hilton making the same face in dozens of photographs).

The Future Ahead screened on a loop inside The Destruction of Experience, an installation resembling a minimalist hospital waiting room. Adorning the walls are calendars displaying graphics about reproduction (“IT’S A PARTY!” one such image screams about childbirth), and in the background, three generic jazz tracks from the “Zara Home” collection blend into a disorienting cacophony of muzak. The “destruction of experience” described in the lecture—plastic surgeries intended to iron out wrinkles in women’s faces, the opposite of Bieber’s trajectory—is a clinical complement to these omnipresent reminders of the “biological clock.” Ulman doesn’t reductively condemn these procedures; instead, she points out how they are an industry built from deeply ingrained cultural expectations. She pivots to a broader tradition of surgically combatting gender normativity by quoting Genesis P-Orridge: “Bodies are just a cheap suitcase for the consciousness.” But this post-ideological ideal collides with how well norms are upheld by an image-based culture, even when fashioning a new self. “Can we judge Justin for adapting to the sociocultural construction of gender?” Ulman asks, as though seeking a way out. It’s not impossible, but the first step is recognizing the root of the matter.

Ulman’s other multimedia projects seek to break this circle, most directly in the form of her own app, Ethira, which she started developing in 2013. Ulman was distressed by the way that Twitter’s emphasis on metrics and branding could adversely affect people grappling with mental health issues, so Ethira’s model was based on anonymity. People could type messages that would briefly appear on the main page of the app before erasing themselves “like water evaporating on a hot stone,” as Ulman put it. There were no profiles; people could share whatever they wanted without the pressure of likes. Because it was so detached from posters’ visual or material contexts, Ulman always envisioned Ethira as anti-capitalist, but capital was still necessary to make the app—and led to its undoing. After a rollercoaster of funding-related fits and starts, a housemate stole the concept and secured investment for his own app, with the ironic hope that it would make a profit. The closest platform to Ulman’s vision is likely Whisper, an anonymous confessions app aimed at teens, but it’s less utopian in practice. Aside from news-making data breaches, Whisper’s photo-based format has recently made it an incubator for bizarre shitposts. Seven years after Excellences & Perfections, permutations of the irony/authenticity ouroboros have only gotten more advanced; even brands like Balenciaga are branching out into baffling promotional images.

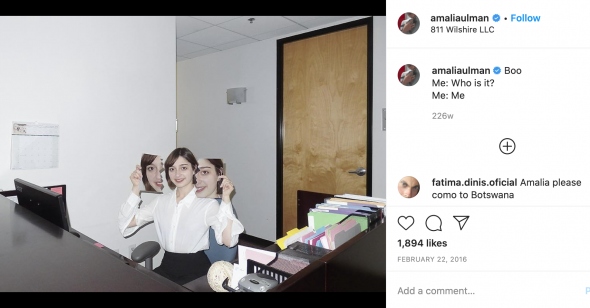

In response to this, Ulman’s second major performance on Instagram, Privilege (2015-2016), leans into high artifice, which she uses to insulate herself from feedback cycles. She sets the performance in a drab office space—each photo conforms to a color palette of red, silver, black, and white—with stylized touches, like fake clouds on the ceiling. As the months go by, she stages her own pregnancy with prosthetics, raising the feminist bodily labor issues in her earlier work. But Privilege is more deliberately heightened and explicitly comedic; in one photo, Ulman watches Family Guy on a TV attached to a Texas-shaped stand, adding “Why can’t I always live in a state of hallucination? I complain bitterly that I’m normal for most of the year.” This mixture of tones could be a mission statement for Privilege: hyperreal with its own set of inside jokes, which build a world of New Normalcy that’s entirely Ulman’s own. The best example of this is Ulman’s sidekick in the piece, a pet pigeon named Bob. The bird, which Ulman adopted and took care of for two years, flaps around Ulman’s office in confusion at first, but Bob soon becomes the star of Ulman’s feed, appearing in New Yorker–style cartoons and impact-font memes. As these graphics accumulate, Privilege starts to dwell in a Bob-ified version of the internet—unexpected for a bird often written off as a ubiquitous annoyance. (Their relationship was touchingly developed in a companion short from Bob’s perspective, BOB LIFE, which gives the unconventional muse his own voice and agency.)

After a while, Ulman could snap a picture of any red-and-black object she came across in everyday life and it would make sense as a “joke” in the Privilege feed, the real world refracted through a personalized tint. Privilege also encompassed a dizzying array of tie-in installations and press coverage: every photo shoot, interview, and even funding opportunity was potential “content” for this character. Real ads for Gucci appeared alongside fake bumpers for the Hulu original Difficult People; Ulman used her own likeness in WikiHow graphics of injuries and ailments, transforming pain into a cartoon; the mere sight of an elevator is reminiscent of Ulman’s video series of rides up to her office floor. Instead of an aesthetic exercise, though, it’s important to note that the performance took place during the 2016 election, an explosion of Instagram-ready infographics about voting and healthcare, images that, however well-intentioned, are the online equivalent of putting up a yard sign. It’s not impossible that they’ll encourage political action, but as Ulman’s earlier pieces prove, the act of posting is usually self-enclosed. To push that point to its limit, Ulman posts a “fashion moodboard” for rocking the vote, embodying the detached “privilege” of living in a state of hallucination, posting for a self-selecting group of followers while untethered from physical consequences.

***

Within the irony and theatricality of her work, Ulman is also a deep humanist. She’s been compared to Cindy Sherman for her immersion into character, especially in Privilege, but she’s mentioned a deeper affinity for Samuel Beckett’s tragicomic absurdity. At times, her art seems closest to the nesting dolls of overanalysis in Thomas Pynchon’s writing. His characters invent elaborate mythologies to cope with a meaningless world, running in spirals that only plop them back at square one. At one point in Privilege, Ulman quotes Pynchon’s Inherent Vice beneath a video of Bob flapping in circles, trapped in her office: “Does it ever end? [Of course] it does. It did!” The caption reads like trying to pull oneself out of a multilayered labyrinth, only to grow more confused, as though manually forcing the brain to stop thinking. Ulman’s work stages a similar battle between interpretive motion and economic conflicts that can’t be reconciled. Before we know it, we’re close-reading fast fashion, hoping for a last-ditch breakthrough.

Ulman’s acting in El Planeta has been compared to Buster Keaton: the movie revolves around her dry humor and her self-protective, deadpan front. The film is a loose amalgamation of Ulman’s autobiography and a real-life tale: she and her mother Ale play the main characters, Leonor and MarĂa, based on a mother-daughter duo of grifters from Ulman’s childhood home of GijĂłn, Spain. The “real” inspirations don’t matter quite so much as the events playing out on-screen, two lives quietly left in the lurch after the death of Leo’s father, who left them deep in debt and whom they mourn less than their cat. Although a stylistic departure from Ulman’s online pieces, El Planeta is a similarly detailed character work about image and persona. The film is comedic and elegiac, slipping between tones as though going through the muted motions of everyday life, shifting with the contrasts of its black-and-white cinematography. Leo walks by newly shuttered mid-century storefronts, reflecting the way that commerce has changed as the world globalizes and moves online. She breaks down crying while staring at a towel that could appear in Buyer Walker Rover, a dishrag with a cartoon penguin (caption: “LOVE PENGIN”)—a dollar-store emblem of the globalized world that’s abandoned them. The film has fleeting moments of escape that stem from Leo and MarĂa’s mutual support, but the lingering scenes are the ones where they let their guard down, vulnerably crestfallen and cast aside by social services.

Ulman reflected on making El Planeta in another performative lecture commissioned by the Tate Modern, Sordid Scandal. She describes the way that film students are encouraged to pitch their projects like TED Talks, often leading to the privileged pillaging inspiration from marginalized perspectives. “It’s like saying tea is your thing when you already know it is a thing somewhere else,” she says. So she decided to mine events from her own life: she describes the process of being discredited in court by her own father, himself a scam artist suing for ownership of the family’s apartment in Gijón. He presented Excellences & Perfections as evidence of her duplicity, and noted how frequently the word “hoax” appeared in press coverage. El Planeta is Ulman’s way of “flattening” these experiences into an image that she could control. The resolution isn’t totally satisfying, the cycles of exploitation only transformed rather than neutralized. Throughout the lecture, Ulman explains feeling like she’s being devoured by her fictional self, the final subject and the final object all at once. Does it ever end? Of course it does. It did.