It Isnât:

The Quibi Anti-Phenomenon and the Narrative Underground

By Chloe Lizotte

A strange, influencer-studded event took place this August on the roof of a mall in Glendale, California: a drive-in screening of Quibiâs original series The Stranger. The series was presented on the big screen in a seamless, feature-length cut, instead of the ten-minute-or-less episodes that gave Quibi its cutesy portmanteau (âQuick Bitesâ). This was the opposite of the streaming service that Jeffrey Katzenberg, the head of Quibi alongside former eBay CEO Meg Whitman, had masterminded, and the event was also two months shy of their announcement in Medium that the app would shut down for good in December 2020. Quibi existed to exist on a phone, with running times geared toward idle minutes spent commuting or queueing; it made itsshows available in portrait or landscape modes, but the service didnât introduce smart-TV compatibility until a scant 24 hours before the shutdown was announced. After a catastrophic app launch in the spring, Quibi seemed eager to cash in on the summer drive-in revival. But Stranger showrunner Veena Sud, best known for adapting AMCâs The Killing from a Danish procedural, didnât think this betrayed their original pitch. In a Zoom Q&A, she speculated that Quibi was only beginning to develop âa radically new way to watch story and interact with story.â

The dropped âtheâ one might expect before âstoryâ might be familiar from press release descriptions of marketing assets: in this context, each âstoryâ becomes a monolithic commodity to be Quibified. That speaks to the appâs obsession with gimmicksâeach episode of The Stranger was intended to populate the app at the hour of the evening that it took place, with a specialized ringtone inviting users to tune in at the appointed time (Sud wonders if people would have woken up and actually watched the new Bite at, say, 3 a.m.). And because Quibiâs greenlit but unreleased Steven Spielberg anthology series was titled After Dark, it would only have been accessible to watch after sunset in any given time zone. But these bells and whistles misread why people might want to watch Quibi, or anything at all. Consider âThe Golden Arm,â an entry in Quibiâs Sam Raimi-helmed horror anthology 50 States of Fright, in which Rachel Brosnahanâs character refuses to have her prosthetic golden arm surgically removed and, as a result, dies in a hospital. The silliness of such a show could fuel the free marketing of a meme cycle if Quibi allowed viewers to take screenshotsâwhich it doesnât. To prove to others that âThe Golden Armâ was real, viewers needed to film choice excerpts with another phone.

That imageâtrash imprisoned in a device, un-shareableâexposed what Quibi had encouraged: an antisocial viewership. It canât conceive of what an interaction with those stories might look like, whether that means individual investment or an actual conversation. As Quibi struggled to clarify what it might offer audiences beyond its superficial design, its commercials ironically acknowledged that the app was essentially a vacuum designed to fill dead time, which critic Dan Brooks covers insightfully for the New York Times. And Quibiâs $1.75-billion-dollar grift, when it wasnât cashing out for Reese Witherspoon to narrate Meerkat Manor-but-with-cheetahs, also relied on exploitation of its crews; projectsâ snack-length chapters kept them from being classified as feature-length, a caveat Quibi used to avoid paying full union rates, as reported by J. Fergus for Input.

A fictional service like Swippi, though, understands this cynicism as precisely the point. The parody app is a vanity project from Craig Healy, a performance art alter-ego for comedian Nick Corirossi: Healy, a washed-up narcissist who speaks in Pig Latin-ish baby talkâhis catchphrase âSet it up!â becomes âSebbadidup!ââstarted as the host of a Tosh.0-style clip show, then pivoted his non-fame and midlife crisis into Cuplicated, an Emmy-baiting autobiographical dramedy in the vein of Master of None (complete with interview segments establishing Healy as auteur, like his hero âCassadavettsâ). After premiering Cuplicated on a fictional streaming service called Vioobuâclearly created by Healy simply to house the show, with a library padded with public-domain sitcoms and educational videosâHealy sensed an opportunity to compete with Quibi. Hence: another baby-named service, Swippi, which breaks the 34-minute Cuplicated down into seven-and-a-quarter-minute segments.

The transparently craven spoof, created by Corirossi and Cuplicated co-writer Scott Gairdner, butchers Cuplicatedâs episodes with the least amount of careâits portrait-mode frames are not even pan-and-scanned, and chop up credits and facesâbut its loud intro and outro bumpers are somehow worse. âWhen youâve got places to go and people to see, take a swift sippada Swippi!â screams a manic voiceover, pairing Healyâs linguistic quirks with images of the places people are supposedly going: stock footage of planes taking off and poorly lit wedding dancefloors, or an office worker covered in Post-It notes, as spiritually vacant as a consultantâs rendering. The time limit brings episodes to mid-scene or -sentence conclusions: âTiiiiiiimeâs up! Time to get back to those places to be and people to see!â yells the announcer. âWhen youâre done, weâll be right here waiting for youâwith more quality Swippis.â In other words, the appâs Swift Sips economize the panic induced by a free moment: they cram white noise into a mind uncomfortable with silence.

****

âInteract with storyâ encapsulates how the largest media companies see experimentation as PR gloss, which may be residue of early-net transmedia marketing campaigns. A movie like The Blair Witch Project, for instance, created an eerie, based-on-a-true-story mystique through web extrasâbut by the time Richard Kellyâs Southland Tales, originally designed as a nine-part interactive cycle spanning graphic novels, rolled around in 2006, it was easy to see how sprawling, assignment-like bonus material might overpower the movie itself. Similarly, mainstream adventures in multi-screen narratives mostly amount to âextended experiencesâ; a mystery series like Mosaic, developed by Steven Soderbergh and writer Ed Solomon for HBO, makes supplemental dossiers available on an app to encourage audiences to research the story independently. Although viewers can choose which characterâs perspective they want to follow, their chosen episodes play out like a straightforward TV show, unaffected by the second screen. Elsewhere, the gimmick consumes the whole: the choose-your-own-adventure conceit of Black Mirror: Bandersnatch treated its characters as nothing more than video game avatars.

Itâs unsurprising that Quibi couldnât incubate out-of-the-box creativity, but its attitude and cash flow speak to the baseline difficulties of producing experimental pieces. Filmmakers working outside of these channels still rely on access to funding, equipment, and screening venues, so their projects still refract the distribution models theyâre trying to circumvent. This is especially true in the film festival and gallery circuit, where Argentinean filmmaker Eduardo Williams has shared a corpus of immersions in the unfamiliar. His films, most notably his 2017 debut feature The Human Surge, are contextless but dense with detail, and if digital connectivity is a fact of these information-saturated spaces, itâs not a roadmap through them.

Williams digs deeper in his 2018 short Parsi, an experiential essay documentary: Williams traveled to Guinea-Bissau with a 360-degree camera and forged some bonds with the queer youth community there. He asked them to carry the cameras with them through the course of a dayâwalking past stormy harbors, zooming down streets on rollerblades, and even tossing the camera back and forth for a stretch. The film presents a live capture of Williamsâs point of view when he donned a VR headset to experience the footage: as Williams cranes his neck around the spaces, the footage is already kinetic. Surroundings blur, and we arenât privy to exposition; we strive to get our bearings in real-time conversations and spaces, but thereâs no blueprint for what weâor even Williams, who also navigates it himself for the first timeâare supposed to âtake awayâ from what we see.

The visuals are accompanied by a voiceover reading of poet Mariano Blattâs âNo esâ (in English, âIt isnâtâ), a poem that Blatt will keep adding onto but never formally finish, with each phrase kicked off by âseems like.â The poem moves all over the placeââSeems like a tired horse,â âSeems like a sandwich shop in Congreso,â âSeems like a Smurfâs spliffââbut flirtatious undercurrents run through it: âSeems like that street corner I told you about,â âSeems like Iâll risk it all for you.â Attraction resembles spectatorship for Williams; in the gap between what you see and what you perceive, an object of desire seems like your interpretation, but it isnât. As the fast pace of the poem overlaps with the hipstersâ conversations, the film reaches a trancelike state: rhythm overtakes concrete interpretation, and this lack of grounding is the goal. As one subject says, âIf the sun is an explosion, isnât it over already?ââParsi is like experiencing that burst of energy as each moment slips through your fingers.

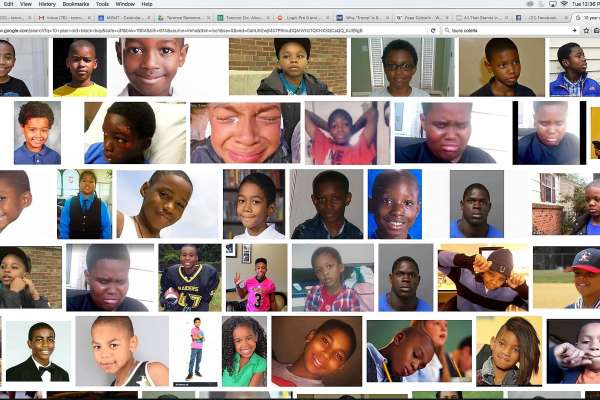

As idiosyncratic as Williamsâs work is, it doesnât require advanced equipment to screen, which keeps it from being relegated to virtual reality sidebars. Considering the practical constraints of a film festival, one alternative to conventional screenings is live performance: Terence Nance brought screen-sharing into a group setting when he premiered his piece 18 Black Girls / Boys Ages 1-18 Who Have Arrived at the Singularity and Are Thus Spiritual Machines: $X in an Edition of $97 Quadrillion (a number Nance landed on as an approximate price for reparations) at Sundance 2017. Standing in front of a projection of his laptop screen, Nance starts with a blank computer and embarks on real-time web-browsing through predictive Google Image searches, moving from queries for âone-year-old Black boy/girlâ up to age âeighteen.â He scrolls through the photo and video results, which verge frequently into disquieting violence, and compiles a portrait of an unpredictable, unsettling algorithm. Nance focuses on how these results are shaped by some unknowable combination of Google searchers and Googleâs interpretations of those searchers: speaking to Film Comment, Nance reflected, âWhether youâve wanted to or not, youâve participated in GooglingâŚso [in the room] it was kind of like, âAm I a part of the data going into this? I must be.ââ By magnifying these searches in public, Nance brings their threatening analytics into the open: each viewer is left to reckon with their role in the raw data.

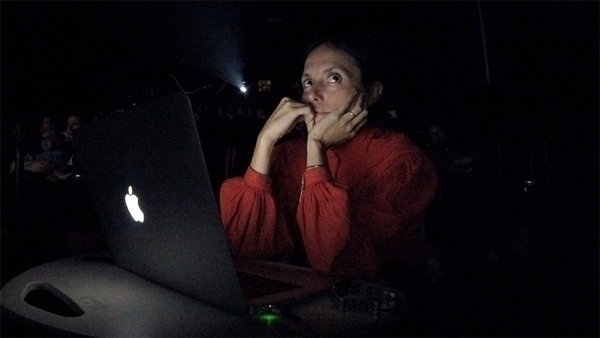

Itâs also possible to subvert the festival circuit, as Zia Anger did with My First Film, which began in public, ticketed settings but expanded to quarantine-friendly livestreams in spring 2020. Anger shares her computer screen to scrub through her unreleased debut feature, Always All Ways, Anne Marie, and comment on the conditions of its shelving. To narrate that fraught production processâwhile moving through financing difficulties and physically exploitative collaboratorsâshe collages a vivid, app-based metacommentary out of written notes, PhotoBooth, and video clips. In the isolation performances, Anger taps into something unique by harnessing the viewerâs laptop, like possessing it. Watching something so personal on an alien screen evokes permissible eavesdropping, which makes the work feel more directâAnger sends individual texts to viewers at the beginning of the production, and at the end of the show, she asks each of them to have pieces of their own creative work on hand to physically rip up in (isolated) unison. This interactivity resonates with the subject of Angerâs piece: reframing, and repossessing, her unseen âdebutâ by encountering it anew and reacting to it in real-time. By inviting others into this personal, alternative space, Anger breaks away from the festival circuit and the âindie film industryâ it suggestsâand lays bare the personal and professional toll of trying to work within it in the first place.

****

Angerâs project suggests a âfree zoneâ that circumvents gatekeepersâbut that freedom only exists to an extent. My First Film, like nearly everything else, depends on apps and programs mass-produced by tech conglomerates. The challenges of trying to create somethingâanythingâof value within these spaces are the subject of James N. Kienitz Wilkinsâs 2017 feature Common Carrier. Pulling it together on a micro-budget, Wilkins designed the film to be unsellable based on unlicensed FM radio interludes; it enjoyed a modest festival run but is now ephemeral, only available upon request. It loosely tracks the day-to-day lives of several artists living in New York, all working from home with varyingly precarious ways of making ends meet, but whatâs striking about Wilkinsâs approach is its density: the entire feature plays out as a double-exposure piece, with two separate video tracks superimposed over each other. The effect is something like Jean-Luc Godardâs Goodbye to Languageâwhere 3D glasses would filter a totally different image into each eyeâalthough less strenuous for the optic nerves. Wilkinsâs superimpositions are both funny and trippily cubist, showing us two different angles of a room, or two characters seeming to merge, or, at one point, a YouTube tutorial to fix a KitchenAid mixer layered over the MacBook Air on which it plays.

Common Carrier also veers between wooden readings of scripted scenes and confessional interviews with the characters/actors, which adds an uncanny air of inconsistent mediation. One of the characters, played by Wilkins, calls a friend from his darkened apartment to ramble about the DCP he lost in the mail, but sheâs outdoors gardening, seemingly worlds away; the audienceâs eyes oscillate between their colliding scenes while he tries, clunkily and with faulty recall, to compliment the esoteric theory in her graduate thesis. Itâs a world where total attention is elusive, if not impossible, which Wilkins sees as a byproduct of dependence on Wi-Fi: itâs a connective tissue that his characters constantly invoke like a running gag, but itâs also a condition of their livelihoods through the likes of eBay side-hustles. Set during the 2016 Verizon strike, Common Carrier is informed by the corporate cashflow thatâs shaped this world; the title references a legal loophole that keeps companies like FedEx from bearing responsibility for lost packages (like Wilkinsâs DCP)âwhich Wilkins reveals in a barely legible, soft-focus Google result. The piece simulates how it feels to toggle between two different screens, halfway able to concentrate on the analog world beyond them, which itself is usually filtered through digital textures.

****

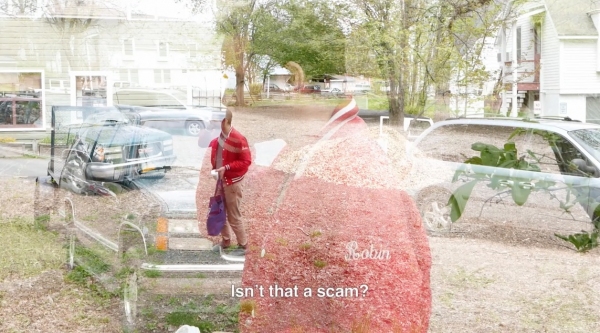

A filmmaker in Common Carrier, seduced by a grant program that seems like a scam, has a pitch for a horror movie heâs trying to sell to Amazon Studios: it centers on an evil monster responsible for a âtsunami of misplaced, useless information.â The concept sounds generic and probably bad, but as he passionately makes his case, itâs clear it comes from an earnest place. At the same time, this is not his dream movie, but a last-ditch commercial pitch to stay afloat during an expensive custody battle for his son.

Artists like Williams, Nance, Anger, and Wilkins arenât building escape hatches from this tsunami of endless IP, but reckoning with the ethical mess of dependence it creates. As neocapitalist whims structure production budgets and streaming libraries, that clear-sightedness is as vital as it is demoralizing to sustain. Nance, for one, managed to make the singularly fluid sketch series Random Acts of Flyness at HBO, but âamicablyâ departed the Space Jam reboot due to creative differences. Wilkinsâs characters, seeming almost to evaporate in their double-exposures, impart a wearied alienation with their own uphill artistic battles, crammed into unstable pockets of free time. As Quibi proves, even a finished product can be ephemeral, since the app has remained vague about whether its series will be accessible or even archived after it shutters. True âalternativesâ may be webs of contradiction, but acknowledging this is an honest step toward more radical possibilities. And with the news that Katzenbergâs farewell email encouraged Quibi employees to draw strength from âGet Back Up Again,â an original song from Trolls, a pop-cultural breaking point could be a welcome change.