Early January of last year, four guys and a girl met in the East Village to celebrate the 25th birthday of one Erik Syngle. The chosen venue was a trendy tapas joint, which on that frozen Saturday evening was bursting at the seams with the usual assortment of black-clad denizens wise enough to arrive early or pay their way to a table. Faced with a long, prostrating wait in a chilly antechamber, we decided to sacrifice potential privilege and adjourn to the more welcoming environs of the Dallas BBQ two blocks away. In that sterile, white-tiled room, over “Texas-sized” margaritas dispensed from something that looked like a washing machine, aside plates piled high with cornbread, chicken, and ribs, Reverse Shot was born.

Seventy-five years ago, young Americans might have dreamt of running off to Hollywood to make it as a star “in the pictures”; forty years ago a generation was growing up fantasizing about being movie directors, but it turned out that these children of the Nineties dreamed of starting their own critical film journal. We began, like many a great undertaking before, by trying to tackle the most imperative, monumental question first, the one choice that would float or capsize our enterprise before it was even launched: What should we call ourselves? The entire course of that fateful meal, was marked by a series of increasingly outlandish title suggestions—Limelight, Grand Illusion, and others too embarrassing to repeat were bandied about amidst much laughter and fervent argumentation. The aforementioned girl, an architect and designer by trade, sat quietly through the mayhem, smiling at the sheer spectacle of us all. At a certain point, probably bored by someone’s continued insistence on the merits of Cine-fuck, she asked “Well, what about reverse shot?” Kate Larsen, our print designer, deserves everlasting credit for plucking that spectral inevitability from the air and snapping us to our senses.

Rather than starting off last year with a plan, mission statement, or set of issues, we decided to put our energies and shared love of cinema into making reverse shot and see what would happen, rather than spending too much time worrying about what it should be (which explains the lack of editorial on this exact issue in our debut one year ago). After a year of doing this, we’re only just starting to see how right Kate’s choice was—it encapsulated everything we wanted to do before we were even able to articulate it. As our ensemble of writers filled out and expanded, our print and online readership grew, and word generally spread, our modest little magazine started to gain a sense of itself and its mission. Too often modern film writing, or art criticism of any kind, focuses solely on cute wordplay, the odd turn-of-phrase, obscure hyper-literate references that irritate more than illuminate, and an unspoken one-upmanship between irony-drenched “journalists” that tries to elevate the writing, yet too often denigrates the idea of criticism itself. Criticism should come not with a frosted dirty-olive martini glass, but with its heart on its sleeve, and a passion for its subject. We love good writing, but we love good films even more.

Black-and-white, good vs. bad, right vs. wrong criticism just can no longer possibly help to buttress a medium that has become so wound up in an a triangular capitalistic stranglehold that now defines the art form. Production, distribution, reception are all now leaps of faith with potentially dire consequences for those involved at every point. Disparate perspectives—from those in critical, professional, and artistic circles—must coalesce in order for something valid to emerge. Perhaps this is our “reverse” shot: new-school academics, up-and-coming filmmakers, and aesthetically attuned specialty distributors understanding one another, reconciling the opposing strands of contemporary cinema. A utopian filmic community? No, but neither is it the incestuous, amoral “everyone’s in bed with everyone else!” downfall that a certain caterwauling New York critic bemoans virtually every week. It’s naive to think of these sectors as being completely separate from one another, and impossible to see the outcome of such a position as leading to anything greater than cranky hermeticism.

Movies must live and breathe; those initially ignored, now languishing on Blockbuster shelves across the country and sitting in Netflix queues from New York to Kansas City, may be at this moment finding their relevancy. Recent Reverse Shot symposium articles on films such as Let There Be Light, 1941, Testament, and Pennies from Heaven attest to that fact. The debate over “is film an art?” may have been won on the battlegrounds of theory a long time ago, but it never ceases to be fought in the trenches of spectatorship and criticism. We demand that film be discussed as an art at every level. We wish for those discussions to continue on, long past the point a film ends its commercial run. We hope you keep watching and we hope you keep reading. —The Editors

[Capsules by Saul Austerlitz, Neal Block, Michael Koresky, Ohad Landesman, Nick Pinkerton, Jeff Reichert, Michael Joshua Rowin, Matthew Plouffe, Suzanne Scott, Erik Syngle.]

1. Kill Bill: Vol. 1

Each new decade lays its own claims to surrogacy over the global village. If ever there was a movement to locate it firmly, Kill Bill: Vol. 1 should be the standard-bearer for the first decade of the 21st century. Look at where we are. Forget choosing between a panoply of local restaurants and ethnic enclaves—click twice, find a recipe and make it yourself. One more click to any music from anywhere that you’d like to hear (albeit illegally, for now). Click again and turn corporate-friendly news reporting into alternative voices from around the globe. Go to your living room and make a choice from thousands of stations. Digital projection systems that will eclipse our world of platters, splices, bulbs, and sprockets offer promise for choices in the theaters that would make the change-’em-up ethos of classic repertory cinema seem staid. The onset of digital has made earlier claims that never before has so much been so close and so bewildering and so exhilarating all at once seem like the naive words of children, and we’re far from the point of knowing how even the most unassuming of new possibilities could turn revolutionary. It is in this milieu that Kill Bill firmly situates itself, virtually breathes it from every frame. This hyper-capitalist landscape has us locked into cycles of desire and want spinning ever more quickly out of control, and though it’s easy to complain that we can never be satiated amongst the flood of sameness we’re being offered, we shouldn’t ignore that we’re also starting to demand much more. Sooner or later the scale is going to tip in our favor. If Kill Bill’s genius is in delivering us our “now” it achieves it by bringing the “more”—images, sounds, scenes, styles, pop-culture references. “More,” and for this filmgoer, pretty damn close to enough.—JR

(Continue reading.)

2. Lost in Translation

Lost in Translation needs no proper introduction. Following the leads of 2001's Mulholland Drive and 2002's Far from Heaven as its respective year’s unequivocal critical darling, reflected in its #1 placement in the Village Voice and Film Comment year-end polls, Lost in Translation is perched in a fairly vulnerable spot all by itself atop the piles of listmaking, which both define and devolve every movie year. Like those two films before it, Lost in Translation has a peripheral interest in abstracting conventional Hollywood narrative forms yet still manages to provide enough accessible emotion so as not to alienate more casual viewers. It’s the year’s requisite bridge between the elitists and mainstream, and thus brings the idea of film as a shared experience to the forefront. Sofia Coppola’s hushed yet streamlined artistry, Bill Murray’s ironic yet soulful detachment, and Scarlett Johansson’s fragile yet self-assured openness all contribute to a film of exquisite contradictions—an aesthetic of hipster removal masks an innate spirituality, a young director sets out to portray youthful disconnect and stumbles upon a study of greying midlife discontent, a romance with no explicit physical connection. Much has been made of Coppola’s dreamlike anti-narrative structure and her drowsy camera’s intimate caressing of actors—yet what’s even more striking is her ability to maintain both dramatic urgency and a deft comic punch throughout. —MK

3. Mystic River

The fatalism of Mystic River, in which onetime working-class kid Clint Eastwood looks back in horrified sympathy on the cannibalistic low-income milieu of his youth, puts the 73-year old director in good company; one would be hard-pressed to cite many artists, cinematic or otherwise, who’ve gotten more optimistic with the passage of time. His film’s recurrent ellipsis, shot in the God’s-eye-view of Steadicam floating over the Flats, could almost invite comparison to the pessimistic, half-blind fogey Kurosawa (spiritual Godfather to the “man with no name”) who directed Ran. But while Kurosawa coldly watched his color-coded tin samurai wage apocalypse through the distant pov of a weeping Buddha, Eastwood pushes in tight, leaves no breathing room of disassociation to squirm away from the sense of sadness and waste. Maybe it’s nearer the truth to say that encroaching old age has drawn Eastwood to the cynicism, if not the style, of his first mentor, Sergio Leone, indicated by an exhumed Eli Wallach appearing in the bit part of Mystic River’s liquor store proprietor? Eastwood’s latest has at least a kinship to the Maestro’s own late-period piece, the self-deconstructing gangster opera Once Upon a Time in America (for which Clint turned down a role), which also bleeds together past and present among a pack of hoods in an ethnic enclave, here Jewish Williamsburg. And certainly when Robert De Niro’s elderly Noodles posits “You can always tell the winners at the starting gate. You can always tell the winners—and you can tell the losers,” he could be delivering a survival-of-the-fittest postscript for Mystic River. —NP

(Continue reading.)

4. The Son

What wasn’t apparent way back during its initial release in January of ’03 was how starkly The Son would stand out amongst the field of 2003 imports as one of the lone films wrestling with this Bressonian strand in contemporary cinema. Not that it should come as any surprise—La Promesse took its cue from the righteous indignation of The Devil, Probably and L’Argent, while Rosetta stands as a high-octane update of Mouchette. As the Dardennes move backwards through Bresson’s filmography, they’ve given us in The Son a protagonist as unforgettable as the country priest, and as similarly conflicted, placed within a thriller structure that builds in tension like A Man Escaped. Working within the long shadow cast by one of the greatest filmmakers who ever lived must grow tiring, but Luc and Jean-Pierre never seem to show any strain. If anything, they seem to be moving ever closer towards cinematic purity—towards an even more lethal brand of moviemaking. Cinema as a whole may be moving away from Bresson, but hopefully some will carry his lessons along into whatever form it moves to take next. Can filmmakers do better for themselves (and for us) than to heed these words: “Rid myself of accumulated errors and untruths.” “ Get to know my resources, make sure of them. The faculty of using my resources well diminishes when their number grows.” “Master precision. Be a precision instrument myself.”

Even if some semblance of this spirit remains on in the work of only a few filmmakers like the Dardenne brothers, Claire Denis, and Bruno Dumont, they will not have been uttered for naught. The Son stands as ample proof that they need not be limiting. In fact, with the barest of tools, the Dardennes have made one of the most consuming, expansive films in years. —JR & ES

5. Spellbound

Spellbound, the documentary by Jeffrey Blitz, is the equivalent of a Matisse in a Mickey Mouse frame. Distracted by the humorous, gauche crust, it is easy to neglect the meaty, satisfying repast contained within. Blitz’s film (his first) follows eight 13-year-olds as they prepare for the annual National Spelling Bee. Like other documentaries of a representative nature (Hoop Dreams comes to mind), the film lives or dies on the basis of the individuals chosen to be filmed. Luckily, all of Spellbound’s prospective spelling champs contain a fascinating world unto themselves. Contrary to its stated intentions, the film is ultimately about the American fascination with competition, family life, adolescence, and talent. Not really contrary, I guess; for the film does follow the progress of the 1999 National Spelling Bee, and does dutifully proceed to the conclusion, when a winner is crowned. But like many journeys, by the time the stated end has been reached, the point of the trip has shifted. —SA

(Continue reading.)

6. demonlover

If demonlover was one of the most scrutinized films of the past year, it was because director Olivier Assayas boldly chose to so directly enter, as well as represent, the new technology at the center of image circulation and the multi-billion dollar entertainment industry. His camera captures manga, animé porn, 3-D graphics, and video games, all readily consumed but rarely acknowledged, especially in contemporary cinema. Its title is apt—the word “demon” originates from the Greek daimon, meaning “divine power,” a term fitting for the status images wield in the 21st century. Connecting image culture with sex and violence within the struggle for global influence via new media, demonlover’s complex plot—concerning Diane de Monx’s entrance into a world of double and triple crosses in her company’s takeover of cartoon porn manufacturer TokyoAnimé—transcends metaphor and enacts a deconstruction of our spectacle-obsessed society. Simultaneously ghostly and tangible—or “there and not there,” as coworker Hervé says of Diane—the hi-tech in demonlover comes directly into conflict with the “ancient” medium of film. The appearance of violent, spastic animated pornography explodes the screen, rupturing linear progression by making time stand still for desire while also initiating a move into transgressive spatial dimensions. Desire becomes control, control becomes power: while the perpetual present of these images loosens time’s stranglehold on life, Assayas doesn’t envision immortality but instead the individual’s endless journey through demon-infested nightmares. Simply put, demonlover is about control. —MJR

(Continue reading.)

7. Irreversible

Much has been made of Elephant’s likeness to The Shining, attributable to its dislocated sense of wandering through the cavernous hallways of a phantom-infested high school. Irreversible, with its myriad corridors of lurking horrors, is itself fashioned similarly, but structured as one uncut backward freefall through a tunnel straight from hell. Told as nine presumably single-take sequences in reverse order (plus prologue and epilogue), the effect is of a continuous underground burrowing back to Earth’s surface—through the hellish nightclub Rectum, back through the maze-like Parisian avenues, to the site of the rape, to the intricate choreography that follows actors from elevators through fluorescent garages and subway cars. The use of the uncut take replicates continous forward motion, a single vision interrupted by occasional camera hiccups and thrusts—even the most innocent scene, the final images of the couple’s doomed reverie as they lounge about their small apartment, becomes a labyrinth of white walls, tousled bed sheets, and intimate kisses. Noé doesn’t just revel in shoving the viewer’s face in filth, he wants us to confront our naivete as both moral philosphers and movie watchers. Irreversible is, if nothing else, a film about narrative complacency. By beginning with the “payoff,” the violent retribution that would normally culminate a rape-revenge melodrama (though here enacted on the wrong man), Noé gives us ninety more minutes of contemplation—the idea of a revenge film that begins with a revenge scene so horrific (a face is pummelled and busted open like a rotten pumpkin, seemingly without cuts) yet so abstracted (we have no idea why this unimaginable horror is taking place) is more than just trickery, it’s truly transgressive. —MK

8. Elephant

What is Elephant? In a key scene, dp Harris Savides places his camera at the center of a roundtable discussion regarding whether or not it’s possible to tell if someone is gay, simply by looking. A collection of teens decry the idea as the typical high school seminar, like, proceeds. The camera pans slowly on point from student to student, and speciously telling voices hit our ears often before the matching adolescent appears on-screen. Utilizing the simplest of cinematic means, the conversation quickly turns self-reflexive; discerning audience members can’t help but hear homosexuality in a young man’s argument against that very idea. We can tell he’s gay even before we see him. And then the face rolls into frame, and that mental image we’d so confidently constructed crumbles away, second-guessing ensues, and an audience reticently reneges, “Well, maybe not. I can’t really tell.” And with a final self-aggrandizing air, “Probably, though. He will be.” Where do we point fingers? How do we identify which 16-year-old is gay or, say, which is planning murder in his (or her) high school? Let’s take a second look. On our behalf, Savides’s interrogating lens leers from behind, fluidly creeps around the side and stares head-on, examining the awkward gait, the dismissive hair flip, pores that define the daily drama of adolescence in languorous long takes. A pre-mortem autopsy of surfaces in the hallways of a scholastic slaughterhouse, through a jaw-droppingly deft reconstruction of an American institution, Elephant grants its audience the chance to do what we’ve all wanted so badly since Columbine: to see today’s high school from the inside out, to pin the tail on the troubled teen we know we could’ve identified with the same confidence backing our crude criminalization of video games, governmental jingoism, and firearm access. To those satisfied with the reductive reasoning of Michael Moore, Van Sant impels that second look and suddenly, it becomes so clearly unclear.—MP

(Continue reading.)

9. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King

That the Lord of the Rings trilogy falls into the category of fantasy is at once ironic and fitting. Fitting, in that cinema has always been concerned with visually mapping the limitless confines of the imagination, and the fantasy genre serves as the ideal vehicle for this challenge: namely, to realize the unreal. Ironic, in that Jackson’s films have been heralded primarily for their realism and sense of authenticity. If nothing else, the trilogy will be long remembered as the cultural moment in which the full promise of CGI was fulfilled. Gollum, digitally enhanced by actor Andy Serkis’s actorly bite, silenced naysayers who argued that synthespians would never emote at the level of their flesh-and-blood counterparts. WETA unleashed organic armies of orcs and oliphaunts that brought new weight to the term “virtual reality.” And everyone, everywhere, finally stopped looking for the puppet strings and got lost in the spectacle of it all. The Return of the King, as the culminating installment of the one trilogy to rule them all (sorry Georgie boy), is firmly entrenched in these aforementioned traits and yet, like the unholy bauble at its narrative core, takes completely unexpected paths to its destiny. Call it a case of purist prudishness, but The Return of the King, unlike its predecessors, is nothing if not shockingly unfaithful to Tolkien’s text. From the film’s Cain-vs-Abel opening flashback of Gollum’s first discovering of the ring (which undoubtedly sent countless fans scurrying back to the book’s appendix to see if they’d missed a few key pages) to its unsettlingly happy-go-lucky denouement (which Jackson had the Gandalfian foresight to begin apologizing for three years in advance), The Return of the King is as much a surprise to Tolkien addicts as it is to neophytes. And perhaps that’s the way it should be. —SS

(Continue reading.)

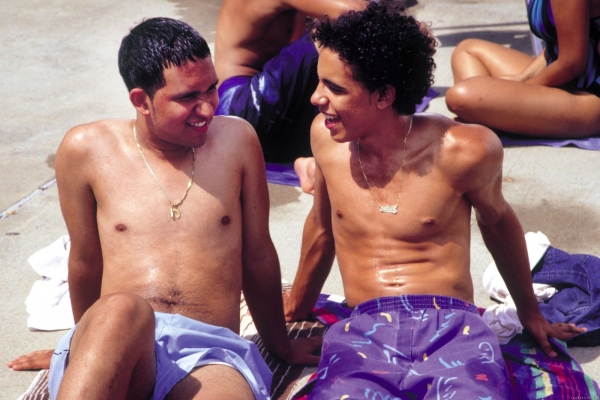

10. Raising Victor Vargas

Vast skies, 18-karat sunsets, proud chickens clucking their way through an alley: just another sweltering July day on Raising Victor Vargas’ Lower East Side. Far from the distant cell-phones abuzz on Ludlow Street, this LES is ostensibly one untouched by prevailing technological trends, a childhood wonderland akin to David Gordon Green’s Carolina from George Washington (the two films share a cinematographer, Tim Orr). Both places, despite pop-cultural references that attempt to establish a specific period, exist in a timelessness that almost exclusively relies on shared memories and experiences to give it form. Victor doesn’t own a cell phone; there’s no computer in the small bedroom he shares with his younger brother and sister. Raising Victor Vargas could have taken place at any point during the last 40 years, on any street south of 14th, in any huge low-income high-rise. Since Victor Vargas is being sucker-punched by the same adolescence that ravaged all of us, this film feels like a chapter torn from our own lives. His surroundings—the buildings, trash cans, public pools, alleys, bodegas—melt into an undebatable, and understandable, teenage truth. —NB