An acclaimed Taiwanese filmmaker working in France; a young Mexican director reimagining a canonical Danish film in an obscure Mennonite community in his home country; a West Coast–based American, enamored of the somber rhythms of the blasted Mississippi delta, miraculously captures them in the kind of American independent film all too rare of late; others from around the globe watching the specificities of home—character, geography, community, and class—evaporate around them. These were the stories of our cinematic 2008, and we’d be hard-pressed to draw any solid conclusions from them, except that passion for those few terrific films that deserve attention always lives, even in those movie years considered less than stellar.

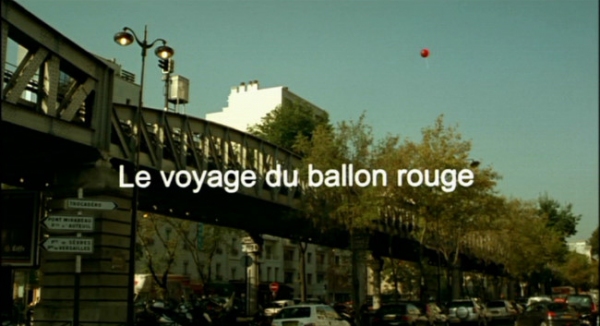

As usual, we polled our major contributors from 2008 and staff writers, with the highest ranked film receiving the most votes, and the rest in descending order. Hou Hsiao-hisen’s Flight of the Red Balloon, it should be noted, was the clear winner, with a lead tally higher than any of the past Reverse Shot first placers. There’s nothing outwardly trendy about Hou Hsaio-hsien’s heavenly masterwork, but it captured something that feels wholly contemporary: even as it recalls Albert Lamorisse’s evocation of France in the Fifties (which also saw a terrific, restored print back in theaters this year), Flight locates its timeless grace amidst the stuff of 21st-century living. Digital editing, video games, piano tuning, pinball: all exist in the same continuum in Hou’s film. Perhaps it is the perfect movie of the moment.— MK & JR

[Capsules by Leo Goldsmith, Eric Hynes, Michael Koresky, Kristi Mitsuda, Jeff Reichert, Sarah Silver, Andrew Tracy, Elbert Ventura, Chris Wisniewski, and Genevieve Yue.]

1. Flight of the Red Balloon

Movies like this one don’t come around very often. The year’s best film, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Flight of the Red Balloon is also, in its unhurried fluidity, 2008’s most deceptively layered: an affectionate, adult riff on a cherished children’s short; a visitor’s humble, open-eyed impression of the world’s most documented city; a hopeful, loving articulation of the universality of loneliness; an elegant exploration of the art and artifices of perception; a cinematic miracle that gamely admits its own string-pulling yet still arrives at true wonder. Song Fang’s nanny watches over a young Parisian boy who occasionally catches sight of a red balloon that seems to gently stalk them both, and Hou’s camera similarly wanders and floats to take it all in. The meandering narrative comes in fragments, yet life appears in full. And in the film’s most powerful scene, a masterful, typically subtle long take, Juliette Binoche’s French puppeteer and single mom crashes into her studio apartment, arguing full blast with her downstairs tenant before slamming the door, grabbing a phone to speak to her absent daughter, then hanging up in tears to see Song busy in the kitchen, her son focused on a video game, the weight of absence, desperation, work, parenthood, and love all descending on her face before she finally realizes that all along a blind man, undistracted by the clamor, has been tuning the recently reacquired piano. “Did you get here okay?” she asks, suddenly shyly smiling, her face adjusting to take in a world even bigger, heavier, and unknowable than her own. Hou’s masterpiece has a similar affect, sending viewers out of the theater to perceive the world differently, better. —EH

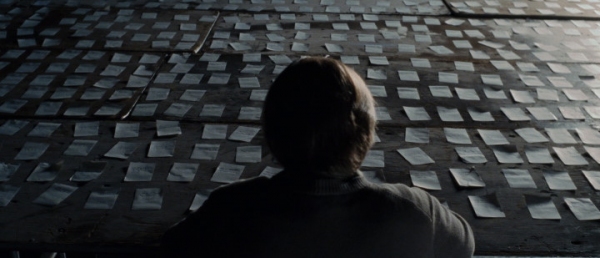

2. Synecdoche, New York

It takes a rare talent to put a fresh spin on a subject as warmed over as the creative process. When that fresh spin comes in the form of a surrealist puzzle box overflowing with verbal puns, discontinuities, impossibilities, and an aching sense of romantic loss, it might just signal the arrival of genius. Of course, first-time filmmaker Charlie Kaufman isn't some struggling ingénue; in the decade since Being John Malkovich his output has morphed his surname into shorthand for an entire mode of filmmaking that, quite frankly, has hit home about as often as its missed the mark. Kaufman proved by taking the reins with Synecdoche that for all the relative successes and failures his past amanuenses (Jonze, Gondry, and Clooney) had in translating his scripts to screen, their interference only muddied the waters of a crystal-clear, scalpel-sharp vision. As his indelible protagonist Caden Coutard's (Philip Seymour Hoffman) theatrical gesamtkunstwerk unfolds, growing in scope to encompass what seems to be the entire world (yet never expands beyond the bounds of his own life), Kaufman's film inches, paradoxically, toward the more personal and local. Synecdoche, New York’s the purest expression of the Kaufman-esque yet; let's loosely define it as a handful of lonely souls struggling to connect in a world filled with complex roadblocks, both external and internal rendered real for us by accumulated reams of fakery and artifice.—JR

3. A Christmas Tale

Is there an enterprise more fraught with artistic peril than one seeking to cinematically wrangle the sentimental sugar-highs and lows of Christmas and cancer? Yet in A Christmas Tale, Arnaud Desplechin exhilaratingly renders the family unit in all its strange and messy glory, inclusive of mood swings and indecipherable inside silliness, minus dysfunctional-family or holiday-movie clichés. Rather than stage the reunion of the Vuillard clan as matriarch Deneuve seeks bone marrow matches amongst her faithful gathered children as an occasion for a group-hug coming together, the director insists on the thorny persistence of history and memory in all familial interactions, even in dire circumstances. No healing of the sister-brother rift imposed by her banishment of him years earlier results from the enforced proximity wrought by illness and season, nor does the younger sibling (Mathieu Amalric, perfectly prickly and unpredictable) forge a bond with his somewhat similarly touched nephew as the trajectory teasingly hints will happen. Instead we’re treated to glimpses of lived-in relationships and constellations, impermeable but recognizable, in fascinating, constant flux. Desplechin withholds, curtails the feel-good vibes at the very instant mawkish momentum might begin to build, instead allowing the snippets of this frantic family collage to merge toward a crescendo of earned emotion that foregoes tearjerking—but it still makes your throat catch. —KM

4. Wendy and Lucy

With all the current talk about failed economies, failed bailouts, and failed presidencies, it’s no wonder that Hollywood has had some trouble putting across many convincing American Dreams this year: failure just isn’t a theme that Hollywood has ever had much luck with. On the other hand, Wendy and Lucy, Kelly Reichardt's follow-up to her 2006 critic-favorite indie Old Joy, effortlessly dignifies personal and financial deficiency with its elegant, low-key narrative of a young woman who loses her dog while aimlessly skirting poverty. Terse and specific, and adapted (like Reichardt’s prior film) from a story by Jonathan Raymond, the film is refreshing in both its narrow scope and broad accessibility, retaining the succinctness and attention to character of short fiction. But whereas Wendy and Lucy could easily have been an academic test case in Emersonian self-reliance or a cutesy neo-Capra-corn girl-and-dog tale, Michelle Williams's tight-lipped, defensive performance as Wendy holds the film's mood carefully in place, withholding as much as possible until the film's final moments. As she traverses a tiny patch of a Northwestern nowheresville in search of her titular canine companion, hers could be the story of any number of Americans: one of the hundreds of thousands displaced by Hurricane Katrina, or the 37 million living under the poverty line. —LG

5. Silent Light

Yes, yes, that opening. The camera descends from a starry night to two silhouetted trees perched steadfastly in a lush countryside, slowly being enveloped by amber dawn. As the sun rises accompanied by a splendid chorus of crickets and morning birds, overemployed cinematic visual terms such as “transcendent” and “spiritual” suddenly feel wholly earned. (I noticed a few poor suckers shuffling into their seats about ten minutes after the film began, shaking my head frustratedly at their now vain pursuit.) The luminous bravado of Silent Light’s introduction, rhymed at its close, threatens to overwhelm the rest of the film, especially since its Ordet debt looms so large. Yet Carlos Reygadas (previously shortsightedly deemed a “provocateur” thanks to the grotesque anti-titillations of Japon and Battle in Heaven, and now wrongheadedly tagged as the second coming of Antonioni or Dreyer) sees his film through, and its triumphal bookends serve to bolster a narrative so pure some have mistaken it for naïve. If days, weeks, months later we remember the spareness of a kitchen table, the insistence of a ticking clock, the rough idyll of a swimming outing, edited as if half-remembered from a daydream, better than the faces or even actions of Mennonite farmer Johan, his wife, Esther, and his waitress mistress Marianna, it’s not because Reygadas has sacrificed character in the name of artistic austerity but that his characters have perhaps sacrificed their lives in the name of faith. And Reygadas has no choice but to capitulate. With his camera, he kneels in awe at his heaven-on-earth surroundings. —MK

6. Happy-Go-Lucky

In the past few years, American films have exhaustively explored the psyche of the man-child, carefully observing his quirks (The 40-Year-Old Virgin) and delving still deeper to reveal his hopes and fears (Knocked Up), as he kicks and screams his way along the road to adulthood, dragged by some beautiful, capable, and decidedly personality-free woman. Meanwhile, in 2008, Britain quietly piped up with a female answer to similar quandaries of responsibility vs. freedom, and proved with eloquence and wit that there are women who don’t automatically turn into career-driven, baby-obsessed shrews when they turn 30. On the contrary, the ebullient Poppy isn’t worried about her job (appropriately enough, she teaches primary school to tots who just about match her energy level) or her biological clock (she doesn’t appear to have one), but rather goes with the flow, learning along the way what works and what doesn’t. Sally Hawkins is larger than life in her interpretation of Poppy, whose life lessons don’t come from a haughty significant other, but from her own insatiable curiosity leading her to take new classes, know new people, and try every day to cobble together what’s been ascertained and somehow grow from it. —SS

7. Still Life

Zhang Yimou’s opening ceremonies at the Olympics might have announced Chinese cinema to the world with more gusto, but Jia Zhangke’s quietly devastating Still Life, a momentary grasp at life along the rising watermark of the Three Gorges Dam, may have been the country’s most vital cultural expression this year. Instead of the revolutionary inventions celebrated in Zhang’s spectacle—paper, gunpowder, printmaking, and the compass—Still Life marks its narrative shifts with cigarettes, wine, tea, and candy, inessential and forgettable commodities that nevertheless mean a great deal to the displaced people living along the Yangtze River. For these “good people of the Three Gorges Dam” (the film’s Chinese title), it’s what brings them together, and it’s all they have. In his signature, irreducible blend of fiction and documentary, Jia presents a world that is literally vanishing, as the dam project, nearly complete after forty years in the making, has forced millions to relocate to higher ground. And it’s these same individuals, those who make their living along the river or seek out long-lost family members, who are changing the face of contemporary China as they demolish and forget the lives they leave behind. Fengjie no longer looks like its printed illustration on a banknote, and while Jia is, as always, carefully attuned to the social transformations of the globalizing nation, his most urgent interest is in the people who survey the altered view. For they, too, move and adapt, hold out hope, and witness strange, startling, and impossible miracles. —GY

8. Paranoid Park

Who is Gus Van Sant? Is he an opportunist, a dilettante, a thief, or just a maddeningly schizophrenic filmmaker? For a few brief months, after I first saw Paranoid Park, I thought I was starting to get it. There was Van Sant the consummate craftsperson, whose dense soundscapes and beautiful imagery (with an assist here from the great cinematographer Christopher Doyle) could somehow elevate sequences of skateboarding teens to the level of visual poetry. And then there was the indie experimenter, shattering his film’s chronology, circling around, over, and through a single devastating event and its moral and psychological aftermath. There was perhaps a hint of the auteur, an artist preoccupied with the dislocation and disaffection of young men, and fascinated by the banal horror of violent death. In an oeuvre packed with oddities and about-faces, Paranoid Park seemed to bring everything together, right down to the Elliott Smith on the soundtrack. Just when it appeared that he had arrived at the point he’d been moving towards since the beginning, Van Sant followed Paranoid Park with Milk (also one of the year’s best films), which marked another major departure—or perhaps a turn back towards the mainstream. If Paranoid Park isn’t a summation—and with Van Sant, it’s really impossible to say—it still may be his loveliest, most ethically probing and emotionally complex work to date. —CW

9. Wall*E

Unlikely images from Pixar's latest: a depopulated earth overrun by garbage; civilization adrift on a space ship for hundreds of years; human beings so fat and atrophied they can barely stand on their own feet; a corporation telling everyone what to eat, do, and think. But there is beauty, too: a Chaplin-esque courtship amid the rubble; a space odyssey of surpassing loveliness; a floating waltz among the stars. And then there's Wall*E himself, curator of our relics, lonely and love-struck geek, a beguiling creation that was the most affecting protagonist in movies this year. Melding Kubrickian pessimism with Spielbergian feeling, Wall*E emerged as AI’s kinder, gentler sibling, smuggling a despairing and critical vision of humanity in a G-rated summer blockbuster. Andrew Stanton's masterpiece took the baton from Brad Bird's Ratatouille—Pixar's previous pinnacle—and ran with it. From here on out, the bar has been set higher: Pixar, we know now, can muster something close to transcendence. The closing credits alone contain more wit and soul than anything Hollywood produced this year, a montage telling the story of civilization 2.0 from cave drawings to wall hieroglyphics to impressionist landscapes. The wondrous sequence is a moving reminder of art's essential role: explaining who we are to us. Wall*E—curious, fearful, empathetic, full of yearning—did just that. —EV

10. Ballast

In independent filmmaking as much as in higher-budget fare, learning is one of the least valued properties for the neophyte, the accelerated, quick-hit mentality of the market largely ruling out a period of apprenticeship or any visible cinematic education outside of cunning swipes from better artists. It’s one of the many heartening things about Lance Hammer’s debut that he shows himself attentive to both the textures, strategies, and aims of the best of world cinema while immersing himself in that evocatively regional aesthetic which has always been the undiscovered treasure of American cinema. Hammer has not simply concocted an opportunistic, hit-and-run redemption fable overlaid with local color; by showing, with great specificity, how (some) people live and learn to live, he puts his own learning process on display. As with another of the best (North) American feature debuts of recent years—David Christensen’s Six Figures—Ballast shows a filmmaker focusing not on predetermined, audience-baiting effects but on a meticulous exploration of various options and strategies, weighing their strengths and painstakingly building a consistent pattern from scene to scene. Ballast is neither perfect nor revelatory, but rather something far more vital: evidence that some filmmakers are still looking and listening, both to their own immediate surroundings and those other films worth looking at and listening to. —AT