In the great tradition of our yearly 11 Offenses column, the absolute bottom of the shit pile (this year, Towelhead; in the past, Trade, The Quiet, and London) is left off, partly because we’ve already said all that needs to be said, but also because lending more brainpower to such soul-sucking experiences would do neither us nor the perpetrators of this refuse any good. We don’t need to swallow back any more vomit as we type precious words; they don’t deserve to see their names further mentioned in any publication.

Nevertheless, there was a surfeit of cinematic swill in 2008, and as usual, it oozed throughout action blockbusters, greedy Oscar grabbers, and foreign imports alike. You know you’ve been waiting for it: here are eleven headache-inducing horrors. [Capsules written by Jeannette Catsoulis, Eric Hynes, Lauren Kaminsky, Michael Koresky, Kristi Mitsuda, Jeff Reichert, Michael Joshua Rowin, and Chris Wisniewski.]

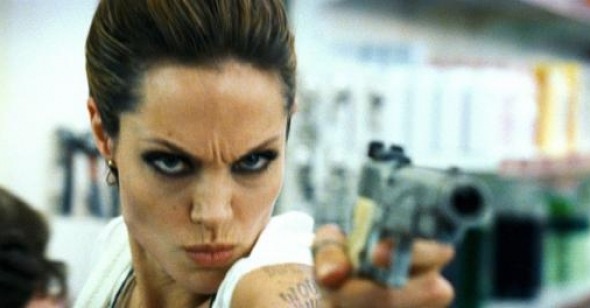

Wanted

Shambling goodness and indulgent devilry fought to a draw in Timur Bekmambetov’s breakthrough genre mash-up Night Watch, a call for stasis that spoke a cheeky truth about beleaguered 21st-century Russia. But Bekmambetov’s first English-language film, Wanted, hasn’t a plausible sociopolitical reality in which to ground its amorality, nor has it a likeable, can-do craft to justify its wearisome fanboy derivations. So sloppily fractured that The Dark Knight seems coherent by comparison, the film peacocks quaint Matrix-era bullet-time effects, video-game violence, and f-bomb-dropping action figures helpfully named Fox (foxy Angelina Jolie), Gunsmith, and The Butcher. Like a cannon-baller in a kiddie pool, Wanted hits bottom fast but aspires to lower depths. Bullets bend and sail over land and sea while Oscar winners play genetically predestined assassins/weavers that receive killing instructions from a code-spinning “loom of fate.” Such spectacular stupidity might have engendered cultish appreciation (many reviewers eagerly took this tack), but Wanted has the bewildering gall to assume a posture of superiority. Everyman hero and narrator Wesley (James McAvoy, the Nic Cage–like slummer of the year) gets yanked from his life-sucking office job to join the league of assassins, learning to shoot first, ask questions later, and chase not wisdom or justice but an apparently imitable blend of fascistic election and, of course, stasis. The film’s final line, a direct-address missive from Wesley to all working stiffs looking for a little wham-bam diversion on a Friday night, drives it home: “What the fuck have you done lately?” To answer: quite a bit, actually, but no, I’ve not recently killed anyone or taken orders from a tablecloth or sleepy Morgan Freeman. I did, however, blow two hours and $12 for the pleasure of being shat upon. Thanks for asking. —EH

Slumdog Millionaire

Here’s one everyone’ll be regretting in the morning, Crash-style. The only, and I mean only, way Danny Boyle’s self-conscious, coolly postcolonial mishmash can be artistically recouped is as some sort of Bollywood send-up. Of course, that would still leave it intellectually and emotionally bankrupt, not to mention such an enormous example of cultural condescension and opportunism that of course it could only become a bona fide blockbuster. And as sought out and beamed to our screens by Fox’s eminently savvy Searchlights, Slumdog has also become the film everyone thinks they have to see. Cinephile defenders call its narrative heap of clichés “appropriation,” while jes’ plain folks call it “simply a good time at the movies,” but do either of those approaches justify its abject-poverty-with-a-techno-beat methods or turgid, repetitive screenplay, which doesn’t feel the need to have its charmed protagonist say anything other than “I will find her,” “She is my destiny,” and “It is meant to be”? Slumdog Millionaire reinforces just about every exoticized Western stereotype of the adorable-hardscrabble foreigner while also foisting upon it an unwarranted, Horatio Alger up-by-the-bootstraps mythology. By the time Boyle stages a Bollywood exit number, so badly danced that he has to cut around his footage, Rob Marshall-style, with the closing credits, it’s hard not to see the disingenuousness (“That’s what they do in those kinds of movies!”). Has it really “struck a chord” or are there just no options when a mini-major takes over the “art house”? Nevertheless, Boyle, that smooth operator, proves that he knows his history of moviegoing flashes-in-the-pan: it’s this generation’s Black Orpheus—come for the colorful poverty, stay for the cool music. Along with Gran Torino, Slumdog might have been one of the top twenty movies of 1959. —MK

Australia

Halfway through this continent-sized mess, a colleague whispered, “When d’you think they’re going to burn Atlanta?” Ultimately, it’s only Darwin that ignites in Baz Luhrmann’s hairy-chested WWII epic, a Wolverine-meets-Mary Poppins romance beset by stampeding cows, evil cattle barons, Japanese bombs, and biological imperatives. None of these, however, are more unsettling than Nicole Kidman. “The strangest woman I ever seen,” opines a half-Aborigine boy in marveling voiceover as Kidman’s Lady Sarah, an English aristocrat, arrives to claim the outback ranch and computer-generated cattle left by her murdered husband. Face polished to a Mattel sheen and body so emaciated I was sure the film was being projected in the wrong aspect ratio, Lady Sarah is the kind of uptight, upper-class woman who clearly needs a good seeing-to, preferably at the hands and haunches of a lower-class male with no table manners. Enter Hugh Jackman, a drover named Drover (because real men have as much use for last names as serviettes), whose thousand-watt smile is at least an identifiable human expression. But Luhrmann, who wouldn’t recognize an authentic emotion if it flew out his didgeridoo, can’t commit to either corn or camp, inflicting flesh wounds on colonialism as the boy ponders his mixed-race heritage (“I not blackfella, I not whitefella either”) and reducing international conflict to no more than an inconvenient barrier to Sarah’s maternal instincts. It takes nearly three hours for our whitefellas to secure their little brownfella, by which time more than Darwin is in ruins. —JC

The Dark Knight

In 2006, a hot-shit British action director delivered a herky-jerky manifesto on terrorism, chaos, good, evil, humanity—exactly the stuff one crams into entertainment to lend it an air of relevance. Given that it was based on real national tragedy, the thing didn't do so well at the box office. A couple years later, another, younger, but still hot-shit British action director has corrected his predecessor's mistakes. Instead of faux-realism, he's dressed his film up in all the monochromatic shades of designer nihilism so as to signify seriousness-of-intent. And instead of a faceless band of heroes standing up against evil, he's collapsed the masses into one conflicted, deeply divided figure with a proclivity for latex batdrag. Attacking The Dark Knight or United 93 on their aesthetic merits is a thankless enterprise—witness the vicious assaults from the slavering web-throngs (who've co-opted serious debate in film culture in favor of multiple exclamations points and ALL CAPS HYPERBOLE) on even the mildest of critics. The issue with both is how cannily constructed they are to produce exactly the receptions they've received, rather than inviting audiences into an honest dialogue around sensitive issues.

This may be a Schrödinger's Cat of an argument, but isn't it convenient that, just at the heaving endpoint of a long national nightmare that's bruised and battered the American psyche, we can look back on the movie year of 2008 and see, sitting atop the box office junk-heap, a blockbuster entertainment that pokes exactly where it hurts? And critics have accepted it as serious art (and not shrewd business) merely because it came from the creator of . . . The Prestige? Please. The Dark Knight is no more than a typically bloated franchise movie infused with a dram of schematic lip service to "big issues," and because it was all "blalck-as-night" or whatever, it got taken for serious. Did anyone leave this thing and get into a deep debate about the efficacy of terror? The ethics of surveillance? Doubtful, except for the few conservative noisemakers who actually did a nice job of equating Batman with George W. Bush. Enough already. God, what I wouldn't give for a cheeky, self-regarding take on spectacle that also encouraged me to think about mortality, the limits of humanity and knowledge, and our shared common origins. Wait . . . sounds familiar. Did Spielberg put out a movie this year? —JR

Revolutionary Road

If Sam Mendes ever really had anything to say about suburbia, the well of emasculating ennui has run dry with Revolutionary Road. Like his Oscar-winning American Beauty, Mendes’s latest traces the growing dissatisfaction of a man, Frank Wheeler (Leonardo DiCaprio), unhappily exiled to the stultifying suburbs with his wife, April (Kate Winslet), and their children. While it’s cloying and smug in all the ways that Richard Yates's novel is not, the film adaptation of Revolutionary Road is nevertheless faithful (painfully so) to its source material. Entire paragraphs of dialogue are lifted from the page and issued from Winslet's over-enunciating lips. Yet, sadly, only the characters' spoken words are transferred to the screen, leaving us entirely without the inner lives that flesh out Frank and April. Yates's unsparing novel compels the reader to see the lost souls behind all these empty words and false pretenses; Mendes's embarrassing film mistakes these pretenses for the point, wallowing in the stagy materialism that its characters despise. Without the opportunity to see beyond the old-timey cars and hats and drinking and screaming, we never have the chance to fall in love with April, and we therefore cannot appreciate the tragedy of her loss. Instead, the film laughs too hard at the expense of women, inviting us to forget that any of these crazy females ever mattered that much in the first place. In the final scene, weak-minded real estate agent Helen Givings (Kathy Bates) prattles on for too long while maniacally stroking her lapdog, so husband Howard (Richard Easton) does the only thing a man can do to survive in Mendes’s idea of a woman’s world: he turns down his hearing aid and tunes her out. Well, same to you, Mr. Winslet. —LK

The Counterfeiters

With such an excess of ink spilled recently on this holiday season’s deplorable abundance of Holocaust-themed or –evoking films (or to be less kind and more concise, “Nazi porn”), it’s been disconcerting to see one of the year’s prime offenders left off the lists. Maybe it’s because it’s already been anointed with an Oscar (for Best Foreign Language Film, which has the honor of being the least meaningful category in an already meaningless ceremony), but Stefan Ruzowitzky's noxious The Counterfeiters has somehow been given a free pass. Like all the others (The Reader, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, Adam Resurrected, Good) that have stunk up theaters this Christmas, this self-satisfied bit of German soul-searching seems to have been designed to win awards; just because it succeeded in its apparent goals doesn’t mean it’s in any way elevated past the others. Not content to depict suffering and despair (which in and of itself wouldn’t make it worthwhile either), The Counterfeiters, you see, is a Morality Tale, which takes a real man’s life experience and reconstitutes it as a what-would-you-do game of Scruples (trademark Parker Brothers). Rascally Russian-Jew antihero Salomon “Sally” Sorowitsch “agrees” to help the Nazi war effort by printing counterfeit money along with a ragtag team of fellow prisoners from his camp headquarters, and Ruzowitzky (whose other exploitation films included the gross-out body-experimentation horror flicks Anatomy and Anatomy 2—sit on that for a bit) twists his “decision” into the fulcrum of a forced ethics-versus-survival narrative. This approach only works on audiences because it appeals to their dubious, movie-honed expectations of martyrdom. Ruzowitzky, whose on-the-nose dialogue and visual choices are as predictable as those in any Hollywood product, claims he made The Counterfeiters as a challenge to himself and his home country, but its slickness is utterly depersonalized, and its pretense to debate reprehensible. —MK

Changeling

Any movie that features Angelina Jolie on roller skates can’t really consider itself a tragedy, especially when her feet are the only things moving in Clint Eastwood’s dreary drama about a stolen child and his bereft single mother. As Christine Collins, a 1920s phone-company supervisor, Jolie skates around the exchange wearing designer vintage and industrial-strength lipstick, revealing nothing about herself or her past. Christine is all mother, all the time; so when the little beggar disappears and the corrupt LAPD tries to fob her off with a substitute, Christine blows her cloche. Like a doll programmed to repeat two or three phrases—“Where’s my son?” “That’s not my son!” “Find my son!”—Jolie (reprising her “Find my husband!” tics from A Mighty Heart) is such a pain I sighed with relief when the cops threw her in the nuthouse. Changeling would have made a pretty good horror movie—Mother, Interrupted—had Eastwood committed to the Cuckoo’s Nest therapy scenes and Texas Chainsaw villain instead of spelunking in his star’s pores. Photographing her like Mary Magdalene (her next role, probably, if Mel Gibson can stay sober), Eastwood leaves the rest of the cast to fend for themselves. He should have remembered that casting John Malkovich as a pastor is like casting Jack Nicholson as a virgin: it only works if the audience is in on the joke. —JC

Mamma Mia!

We tried to warn you about Mamma Mia. Perhaps words like “laughable,” “amateurish,” and “embarrassing” simply weren’t adequate to describe the grotesque ineptitude of the thing. Maybe you really had to witness every ill-conceived shot, cut, note, and dance step to grasp the immensity of its badness. “But we could watch Meryl Streep in anything!” you insisted, and honestly, we used to think so too. “And who doesn’t love ABBA?” you continued—and you’ll get no objection here. “We needed something fun to divert our attentions from Afghanistan and Pakistan, Sarah Palin, and the collapse of the world economy,” you pled. And we, too, would've given more than twelve bucks for a little musical escape, a “Gold Diggers of Aught-Eight” to chase our blues away. Still, we pooped on the party, but our protestations fell on deaf ears. Our detractors could be right: we may be nothing more than snotty curmudgeons. Who needs singers who actually sing, or a director who has any sense of where to put a camera, or editors who demonstrate any understanding of spatial and narrative logic? So what if Pierce Brosnan sounds like a muppet? And is it really so racist to put the wild-eyed black bartender in a diaper? Six hundred million dollars later, no one cares what us snarky brats at Reverse Shot had to say about Mamma Mia. Since we actually love movie musicals, though, the only thing more disheartening than watching Mamma Mia was reading about its success. Was it really so wrong for us to expect competence from a multi-million-dollar Hollywood product—or to hope that movie audiences would care to expect the same? —CW

The Wackness

And this year’s Little Miss Sunshine or Juno is . . . not The Wackness. And thank fucking god. Surely Jonathan Levine’s Summer of ‘94 bildungsroman had all the makings of another Sundance-approved “breakout”: slang-slinging teenagers (this time you’ll sigh at the antiquated lingo!), “quirky” family members, lazy fallbacks on pop-scored montage sequences, life lessons learned in audience-coddling wrap-ups. To be fair, The Wackness probably deserved to succeed just a little more where its would-be predecessors deserved to fail, even if just on the basis of going for an unfashionable—yet still lame and unconvincing—mid-life crisis/leaving the nest soap opera earnestness. But not quite. Because The Wackness is the kind of film that has to hard-sell its retro setting, hammering home at every opportunity the sheer novelty of taking place in the era of Giuliani’s New York with a force that could only be wielded by a screenwriter desperate to garner kudos for “evoking” a just recently nostalgicized era. “This is by B.I.G.,” says Josh Peck’s hip-hop wannabe as he passes his crush a Walkman. “Just came out.” CATCH THAT? THE FILM TAKES PLACE IN 1994. I would have screamed mercy at the half-dozen mentions of Kurt Cobain’s death but was rendered incapable of speech while watching Ben Kingsley make out with Mary Kate Olsen and listening to the movie’s unironic “become a man, son” advice: “Try to fuck a black girl, I never did in college.” Again . . . not The Wackness. —MJR

Transsiberian

High hopes for Brad Anderson’s Transsiberian—kept aloft by the film’s occasional straying from thriller tropes to gaze into a character-driven existential distance—are infuriatingly dashed by its conventional narrative unraveling, in which the director (also co-writer) cracks a whip to tame an unruly female protagonist. Seemingly mismatched couple Jessie (Emily Mortimer) and Roy (Woody Harrelson)—the former a reformed wild child, the latter a bespectacled straight arrow—embark upon the titular express as a concession to Jessie’s wanderlust following Roy’s church trip to China; but the set-up’s inevitable Hitchcockian echoes soon fade. After an excursion into the Siberian forest ends with Jessie killing Carlos (Eduardo Noriega), a fellow traveler to whom she’d felt a strong attraction, the movie leaps into straightforward suspense mode and leaves behind its intriguing generic indeterminacy. Even the stunning ambiguity of the murder—did Eduardo’s aggressive sexual overtures justify Jessie’s self-defensive slaying or was she overreacting?—attains revisionist closure at film’s end by a police officer’s mention of prior sexual assault charges in relation to the dead man. And, most offensively, Mortimer’s complex characterization of a woman torn between the stability of marriage and a life less ordinary finds simplistic resolution in her total conversion from adventurer to loving, devoted wife: Her ambivalence about having children and settling down dissipates in the face of scary Russians, predatory lotharios, and a big, bad world, as evidenced in a discordantly sappy concluding moment when she reacts responsively to a cute kid. While the spirited heroine of Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes allegorically rages against isolationism—and, in thus doing so, gains the confidence to liberate herself from impending marriage to a man she doesn’t love—Transsiberian’s Jessie regressively learns a woman’s place is in the home. —KM

Pineapple Express

James Franco’s porn-stache and jheri curl in Milk can only have been some sort of cosmic retribution for his headlining turn in Judd Apatow’s, er, oh my stars, excuse me, David Gordon Green’s Pineapple Express. Granted, Franco is the only watchable element in this over-hyped wannabe stoner-classic, but his affable “anything goes, bra” demeanor only serves to put a deceptive, blissed-out smile on what is a surprisingly mean-spirited and smug exercise in misplaced “Movies for Guys Who Like Movies” nostalgia. For anyone who takes a “Chill, dude, it’s just a comedy” approach to the accusation of homophobia in Pineapple Express, take a closer look at the amount of laughs meant to be gleaned from the icky sight of two guys professing their affection for one another. Superbad managed to circumvent this by imbuing its climactic sleeping-bag confessional with genuine feeling (you truly got the sense that these high-schoolers were lovingly joined at the hip), while the preposterous Pineapple constructs some sort of makeshift “bromantic” comedy spectacular in which Franco and Seth Rogen (time to take your one note and go away, now, Seth) meet-cute over pot, and then, over the course of some badly staged car chases and shoot-em-ups, fall madly in love with each other, in that sorta not-gay guy way—as we’re shown over…and over….and over. In-between all this nonsense, we get a very lost Rosie Perez as a humorless butch cop; Rogen’s nattering teenage love interest, whom he predicts will go all “lesbian” in college (cuz thatz wut girlz do, amirite?); and a pair of henchmen whose intended humorously homoerotic banter (intended to parallel the protagonists’?) brings the whole movie to a nasty, screeching halt. And also, note to Apatow, Green, & Co., it’s not inherently funny to just show a big bag of pot onscreen: clever plotting and one-liners also help. —MK