Ghost Writer:

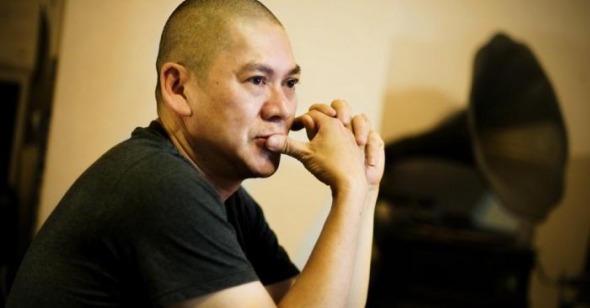

An Interview with Tsai Ming-liang

by Jeff Reichert and Erik Syngle

Reverse Shot: You opened the Q&A after the Harvard Film Archive screening of Goodbye Dragon Inn by asking if the audience liked the film, which struck me as a really generous gesture. It's really one of the only times that I can remember where I've seen a filmmaker acknowledge the audience so directly.

Tsai Ming-liang: It's actually something that I don't do very much, but the screening came so close to the Boston opening that I wanted to get a sense of what the audience thought. In times that I do ask, I make sure to tell the audience that if they didn't like it, not to tell anyone.

RS: The fact that so many people seemed enthusiastic about Goodbye Dragon Inn left me curious-the pleasures in your films can often be hard won, and this is certainly one of the most difficult of your films in terms of navigating through it. It certainly seems to be the most “still.” Given that you're using long takes as pre-conditions for humor, how much of this staging is the result of your theatrical background, or is this something you've just arrived at over time?

Tsai: Someone asked me a very similar question yesterday at Harvard, and I'll give you the same answer: when I can use one shot, I won't use a second one. But if you look closely, I often move the camera slightly, often when I'm following the characters. It does have to do with my theater training-there you don't have a camera and are dealing with real space and time issues which I've tried to carry over into my filmmaking.

RS: Given that the camera is often stationary, and these shots often are long and hinge around a small gesture, what does a Tsai Ming-liang script look like?

Tsai: Screenwriting is my least favorite thing to do but I have to go through the process to a certain extent so as to provide something for my crew to work from. To be honest, I don't really believe in them. Normally, the actors don't get to see the screenplay and we base a lot around discussion. What I do provide often looks more like poetry-descriptions of a certain mood, an effect to be achieved, and maybe a critical movement. There's an award for screenplays in Taiwan, which I have never won because they say my screenplays are too simple. A screenplay is often used to provide a structure to the film that is going to be made. I spend most of my time in what would normally be the screenwriting process, thinking back to the reasons why I wanted to make that particular film in the first place. What's more important for me are locations, and really working with the actors to make sure they understand the effects I'm trying to achieve.

RS: Your films are all very funny, except perhaps The River…

Tsai: I think The River is very funny.

RS: Okay, okay—maybe it's just the ending that isn't so funny. But do you find the humor in your films translates well, especially given your rigorous aesthetic? The humor seems really indebted to Buster Keaton and inheritors of that tradition, like Tati.

Tsai: Well, there are always people who “get” my humor and those who don't. It's pretty much the same everywhere I go. But you're very right when you bring up Buster Keaton-for me he's is one of the greatest comedians. Today, I don't know if comedy still exists. I think the best comedians are always those that have the least expression which is why I don't find Jim Carrey particularly funny, and why I strive to keep my actors expressionless. It's always the situations that characters find themselves in that make things humorous.

RS: That's very true. So much of American comedy now is centered around language and talking, but your films are all about space, situation, and setting.

Tsai: Yes. People have asked me questions about sadness and humor in my films, and I don't think I purposely want to make a “funny” film or a “sad” film, but I think I need these elements as what I'm really trying to do is replace story. I don't want to tell stories. To keep the audience interested, I need to introduce something so I choose to magnify details of situations and that often leads to humor. Happiness and sadness are really parts of the same thing, so often the absurdity of a situation makes it seem funny, but the core of the moment is really quite sad.

RS: If you say you're not interested in telling stories, which is so often the sole goal in filmmaking, what is your goal?

Tsai: The movies that we know today are so dominated by storytelling. My question is: is film really only about storytelling? Couldn't film have other kinds of functions? This question brings me back to my own experience of film watching. It's very rare that I remember the story of any film. I usually only remember a certain moment that touched me. Take Bresson's Mouchette—after Mouchette is raped, she has to go home to feed her sister. She's carrying this bottle of milk, but she can't find matches to warm up the milk, so puts the bottle inside her coat. A very simple movement, yet it really moved me. Of course my films have something like a story. But I direct my attention to daily life and living. In our own lives there's no story, each day is filled with repetition. Movies today feel like in their two hours they have to tell a story so they're filled with indexes and indicators to point to the completion of a story. The audience has gotten used to it. I think film can be more than just that. I believe that the stories of my films can all be told in two sentences. Like in The Skywalk Is Gone: Lee Kang-sheng and Chen Shiang-chyi walk past each other but don't recognize each other. That's it. I'm trying to remove the dramatic elements from the story to disguise it. Film and reality are different, but by removing that kind of artificial dramatic element, I believe that I'm bringing them closer.

RS: The most obvious question to ask about Goodbye Dragon Inn is: why are we saying “goodbye” to King Hu's Dragon Inn? And why are we saying goodbye to this theater, and this bathroom, both of which figure in What Time Is It There?

Tsai: Actually, the Chinese title for Goodbye Dragon Inn is not that at all. It's Bu san, which is really difficult to translate into English. It's meant to describe something like things coming together not to be parted, so it's actually quite the opposite of “goodbye.” There are really two different meanings of goodbye-in one case you might be seeing the person again, but in another you might not be. In this case, we will not be seeing the theater again as it is being closed down. Dragon Inn is significant in that, for me, Hu's film really represents the Golden Age of Taiwanese cinema. It represents the quality of those films that were made during the sixties. That's why at the beginning of my film I show you the entire credit sequence of Hu's film. This is my way of paying respect to filmmakers of that day and re-present them to new audiences. I never wanted to make Goodbye Dragon Inn—it was not a film that I had planned to make. But when I was scouting locations for What Time Is It There? I discovered the theater in a small town outside of Taipei. I got to know the owner and shot the segment there. A few months later I ran into the owner again and he told me that he was going to have to close the theater. Audiences were small and it was now mainly a cruising place for gay men. It was just an impulse—I leased the theater for six months. I had no idea what I was going to do and thought I'd just make a short film, but I wanted to try to capture something of it on film. I feel like it was the theater that was calling me to make the film. That theater reminded me of my experience growing up in Malaysia. At that time there were seven or eight grand theaters like that, that have disappeared one by one over the past few years. Prior to making Dragon Inn I was having this recurring dream of this particular theater in Malaysia. Its almost like these images of childhood wouldn't let me go.

RS: That's interesting, since superstition seems to be a recurring element of your films that gets picked up in the talk of ghosts in Dragon Inn. Do you tend to avoid black cats and walking under ladders or are you commenting comically on a strand of it you see in a Taiwanese society trying to reconcile tradition with modernity?

Tsai: I am very superstitious and I believe in ghosts, which is why there is talk of them in the film, and so many old things. There are many traditional elements in Goodbye Dragon Inn that might not be immediately apparent. For instance, the bun that Chen Shiang-chyi gives to Lee Kang-sheng is something that we give on birthdays, but also something used for ancestor worship. The fact that she has this tells us that she's from a very conservative family. On Chen Shiang-chyi's desk there is a romance novel which is the first I ever read when I was in fifth grade. It was by a novelist who was very popular at the time. When I saw that exact edition by chance in Hong Kong and I had to buy it and decided to include it in the film. To include these kinds of elements is my prerogative as a director. This inclusion of older elements had something to do with the theater and the fact that it seemed so unreal. It has a quality of crossing across time and from the human realm to the non-human. Whenever you enter a theater you are actively giving up your own “real” time. That provides a sense of mystery.

RS: It's interesting that Chen Shiang-chyi presents this bun, this element of homage and tradition to Lee Kang-sheng who is the projectionist, a figure nominally in charge of everything that's happening in Goodbye Dragon Inn and an actor who features so centrally in the other films.

Tsai: I like it because for me, the shape of the bun is very similar to the shape of the heart. But, a year prior to the making of the film, I was guest lecturing in Thailand and there was an animation student there who was using it as a model for a women's breast. He was keeping the bun in the same rice cooker that you see in the film, so a year later it popped up again.

RS: To what extent could you say Goodbye Dragon Inn is specifically choreographed to go with certain scenes from Dragon Inn? It feels at some points that the onscreen dialogue is picking up for the lack of conversation in the theater. Or are we just being teased with the possibility of that coherence?

Tsai: The two films are very closely related. In King Hu's films, he pays a lot of attention to public spaces, so there in Dragon Inn there is a focus on inns and temples, and then of course the theater is a public space, so the two are responding to each other. In the earlier film, a group of swordfighters are protecting a boy from evil and the most dangerous space they have to go through is the Dragon Inn. So in the scene where Chen Shiang-chyi and the female swordfighter share a mutual gaze, I'm trying to show that movies can serve as a mutually encouraging force. In this case, urging Chen Shiang-chyi to continue. She has a difficult task-to walk the long corridor and deliver the bun. The Japanese character in my film is on a quest. He's entering an unknown space full of possible danger, just like the swordfighters. And the two older actors, Chen Shih and Miao Tien who appear in both films play a very interesting position. They are both objective watchers, but they are being watched. The audience doesn't necessarily need to know that they are also watching their young selves-it could just be two old men admiring the youth of the swordfighters. A contest of youth and aging. Film can keep something eternal. It saves the youthfulness, but it's also dying as well. Whatever you film is slowly dying at the same time. Whatever you film is no longer there.

RS: Goodbye Dragon Inn seems very nostalgic for a way of films and viewing films that seems ever more rare. More and more of our old theaters close, or get carved up into smaller and smaller houses. Are you worried that at a certain point we're not going to go to the movies together anymore? Are we going to just sit at home with our living room theater-fortresses which we are more and more being encouraged to do?

Tsai: People our age have the collective experience of moviegoing, but today the experience is different with DVD, satellite, etc. You see these major changes over the past ten years and it hits you the speed of things, how fast these changes are happening. But there's no way back. There's no use worrying or feeling sad about things. But it's also really hard to tell the younger generation about how things were in the past, and vice versa. People who are sober-minded and not really affected by the political structure are able to see how these changes are happening and how we are really controlled by very few politicians and businessmen. And voluntarily. Fewer and fewer people are aware of this situation.

What makes older films different from today's films is really about values and the messages that they send. Even if you compare good films made 20 years ago with the films of today you can see how different they are. What's worrisome is the change of values. There are no messages in today's films besides narratives about quick roads to success. Characters don't have to work very hard to be successful. Like in Legally Blonde—the actress makes a speech, everyone applauds. New films are all about clapping. Older films are more humane. The whole world is being affected by Hollywood. New national cinemas always want to imitate it-take Thailand and Korea. The feel like if they make something uniquely their own it won't make money. This has become a very deep-seated belief. I attend conferences and talk about these issues and people look at me like I'm from outer space. I really feel that you need to make things that are personal, local and unique.

RS: There is all this worry about tradition in the film, and how tradition is being worn away. But the sign at the end says the theater is only going to be closed temporarily. Is this a hint of optimism? Might the theater open again?

Tsai: Actually “Temporarily closed” in Chinese really means “permanently closed.” They don't want to say something bad, so they always use the euphemism. The film is really not just about the theater. It's also a way of expressing feelings or love. Chen Shiang-chyi is so old-fashioned. The way she expresses her love is so subtle, so unique. She gives herself, just like the old theater accepts everyone, both of which I think are qualities that are disappearing. We are powerless to stop the changes, but at least by making this type of film we can document them in some way.

RS: I feel like the most emblematic image from your movies is Lee Kang-sheng wearing white underwear, and was somewhat distressed in Skywalk to see he had switched to black. Is this a harbinger of things to come for this character?

Tsai: The fact that he wears black underwear is less important than the fact the he puts on the doctor's coat. Skywalk is really about disappearance and change, not just the physical environment. Changes of identity and loss of self. The doctor's robe is a very common symbol in Japanese porn which always stands for an imminent loss of self. My continual interest in my characters has allowed me to track their lives, and in the next film, The Wayward Cloud, there's still a two-sentence story, but it's about the changing conditions of Lee Kang-sheng and Chen Shiang-chyi's characters. This is the first film that puts the two in contact with each other. They're going to be falling in love. Which is funny because it's an erotic musical. The first shot of Lee Kang-sheng in the film is him wearing the doctor's robe. You might even want to call it a silent film because there's only one line of dialogue.

(Translation by Shujen Wang, Emerson University)