Innerspace

Ken Chen on The River

Tsai Ming-liang's The River begins with its protagonist pretending to be a dead body. Xiao-kang (Lee Kang-sheng) has been recruited by a film director to replace her previous actor (an inescapably fake mannequin) in the role of Drowned Corpse. As Xiao-kang wades into the river and floats face down before the cameras, he inadvertently becomes symmetrical with the role he's playing: the river pollutes him, infecting him with an inexplicable sickness that he and his father (Miao Tien) spend the rest of the movie trying to exorcise. The director turns to one of her assistants and yelps that Xiao-kang is way better than the dummy. A more literal translation might read: “He's much better than the fake one.” This is an oddly cheeky preface for The River, the Taiwanese New Wave director's most psychologically careful film and one of the greatest movies of the 1990s. Can you think of any other neorealist movies that begin with a film crew declaring that they prefer non-actors over the gaudy special effects of a chalky doll? And that they prefer the non-actor precisely because he is more real? Yet Tsai Ming-liang is an irregular realist—reality is his means, but he wants his results to be spiritual.

We must start out by noting that, like every Tsai film thus far with the possible exception of Goodbye, Dragon Inn, The River stars Lee Kang-sheng as a young Taiwanese guy called Xiao-kang (which incidentally means “Young Kang,” having the same relationship to the actor's real name as “Bobby” might to “Robert”); his parents are again played by Miao Tien and Lu Hsiao-ling; his gamine love interest by Chen Shiang-chyi; and the unattainable male romantic figure by Chen Chao-jung. The locations—Tsai never uses studios—themselves constitute a cast of personalities: The River starts with a pair of up-down escalators that reappears in his 25-minute featurette The Skywalk Is Gone with the same two actors (the skywalk itself seems to make a cameo in The River), and the family apartment appears to be that of What Time Is It There?, Lee Kang-sheng's actual apartment, complete with red rice cooker and ghostlike white fish. This is more than IMDB scholasticism; Tsai repeats these found objects until they've burrowed themselves into authenticity, reusing the same actors and settings in each film until we've habituated ourselves into accepting them as having been always real. The plots themselves form a deliberate mirror against the lives of its actors: Tsai adapted the plot of The River from an unexplained illness that Lee Kang-sheng endured for almost a year; What Time, a film that begins with the death of Xiao-kang's Dad, was similarly produced shortly after the death of Lee's own father. Both films respond to these calamities with theology: the funeral ceremony for Xiao-kang's Dad is Buddhist, just as in The River, Xiao-kang and his Dad use Buddhist exorcism as their medicine of last resort.

The subject matter here is spirituality, but reality and spirituality for Tsai are more than empirical specimens ready for collection—they constitute his aesthetic style. How does one capture spirituality without resorting to mystery? How does one portray the ineffable through the concrete? One way is motif: Tsai likes the cycling wheel (a Ferris wheel closes What Time Is It There? and a projectionist's reel closes Goodbye, Dragon Inn) and water (every Tsai film is soaked with ceiling leaks, bathtubs, or soppy skies; Rebels of the Neon God's use of a floating sandal incidentally predates Wong Kar-wai's same image in Chungking Express by two years). But excessive symbolism cheats reality by replacing it: the realist storyteller who uses symbols gives up stylized depiction but then takes up a stylized content. Tsai's more profound solution is to become a poet of space. Tsai poeticizes space not by probing it—his oeuvre is noticeably lacking in pans, zooms, and dollies—but by making space itself his medium, manipulating its grammar the way a poet might play with diction and sentence structure. Tsai positions the action in the background of a shot (say, 30 feet behind where the heroine is sitting in the foreground, as in What Time Is It There?) or shoots from so far away that a tiny protagonist is embedded in an Andreas Gursky–like panorama of skyscrapers and toy cars (as when Xiao-kang changes the giant clock, also in What Time). This toying with space recalls classical Chinese poetry—most notably the Tang Dynasty poet Wang Wei, whose painterly poems set different spatial modes against each other, positioning a darting bird against a ponderously setting sun and merging the blue of sea into the blue of sky, which split apart into different blues only when a coastal city appears on the horizon.

Social space is also space; it's what humans do to physical space. Tsai has an architect's sense of humor, his is a jokeless comedy about what happens to people's private spaces when they're punctured. In The River, the father's bedroom roof starts leaking and, after some diligent bucket-carrying and floor mopping, he finally strings together a ridiculous plastic hose to siphon the leak into his balcony—so he can water his plants! (The film's harrowing bathhouse conclusion is an accident of shared space, as well.) People are also space—just space with soul. This explains why we know everything about Tsai's characters except what they're thinking. His characters seem like strangers even to themselves, not necessarily because they're alienated, but because we have access to their bodies, rather than their selves. We are omniscient rather than intimate.

Because film is a two-dimensional medium, space for Tsai is a fruitful problem, the same way motion was a problem for static artists like Moholy Nagy, seminal Marvel Comics artist Jack Kirby, and the cubist painters. Tsai is a tender exorcist trying to summon space, trying to yank the ghost of spiritual space from out of mere location. This realization has led me to connect Tsai’s aesthetic to the writings of Martin Heidegger, the German philosopher who died in 1976. Heidegger formulated his philosophy of Being (what it means to exist) by rejecting the assumptions of the preceding philosophical tradition—that Being was an abstract ideal, existing outside of empirical time and space, and something best understood by a pure, disembodied, exclusively analytical self. Heidegger instead suggested that we're lodged within the world—not angels, not master logicians, just human creatures going about our theory—less default habits, sweeping the floor or ironing shirts.

Heidegger implants Being directly into man. And in Tsai's cinematography, almost every camera angle could credibly be the perspective of a human inside the scene, as if we ourselves were embedded in the environment of the film. Thus, the characters in Tsai's movies, when viewed in the theater, are the same size as we would see them in real life. So while Tsai has been criticized for a precious kind of neorealism, his movies simulate one of the least pretentious activities of all: people-watching. Both Heidegger and Tsai seem to believe that what it means to be human is best understood through looking at man's practical engagement with the world. Tsai's films inspect these shards of everydayness, until man turns transparent and we see the light of Being illuminating him from within. For Tsai, the shot is a field of observation, more like a café window than a photograph. Because each shot becomes equivalent to an onlooker perceiving an experience, the shot becomes the scene, each shot sealing itself into a self-contained box of phenomena. In this respect, Tsai might be compared not to Antonioni but to King Hu, whose 1969 wuxia film A Touch of Zen spends its first hour almost devoid of fight scenes, content instead to delve into wheat-plumed walkways, derelict villas, and cloud-hatted mountaintops with more patience than the typical Mizoguchi movie.

Unlike most directors, Tsai understands film not as a toolbox of visual and narratological manipulations but as a metaphor for ordinary sight. Most film editors smash space apart by editing “analytically”: the first shot (called the master shot) presents the entire scene (say, a dialogue between two people at a café), followed by short component shots that highlight whatever's of interest (cutting to A when A speaks and to B when B speaks, for example). For Tsai, every shot is the master shot: one imagines that these component cuts would seem fake to him, not nearly holistic enough to present the characters' surrounding context. Tsai instead uses what could be called logistical editing: the cuts are determined not by the needs of the narrative but the needs of the character's relationship to his tasks. In The River, Xiao-kang's neck hurts so he sees a doctor, a chiropractor, an acupuncturist, and an acupressurist—each visit is one shot. Xiao-kang's Dad sifts through junkyard trash to cobble together his leak-prevention devices, and Xiao-kang's mom mills around in an elevator, waiting to reach the restaurant where she works. If the point of plot is merely to coerce the audience into tears and guffaws, to taxi the highway from exposition to denouement, then these details are hardly relevant—but from the point of view of the characters, these moments are crucial because it is what characters did. This is why after watching enough of Tsai's work, other films start to look like only summaries. And like Heidegger, who thought of a hammer not as a set of hammer-defining properties but as a tool for hammering, Tsai is fascinated with the thingness of things. Few actors outside of Chow Yun-fat, Buster Keaton, and Jackie Chan are as eager to interfere with the world as Lee Kang-sheng, who's always fidgeting with wristwatches, compasses, windowpanes, clocks, toothbrushes, watermelons, and curtains.

Of all of Tsai's films, The River is the fullest. Like Maurice Pialat's Van Gogh and a number of recent Chinese language films—Edward Yang's Yi Yi, Hou Hsiao-hsien's City of Sadness and Jia Zhangke's Unknown Pleasures—it is fatly minimalist, a neorealist film filled to the brim with life. This tragic but undevastating filmmaking, this metaphysics of street corners and silent skinny guys, results in a funny syncretistic aesthetic that makes Tsai look like the heir of contradictory traditions. On one hand, he insists on reality, on unacting and on subtext-rich location shooting, making his films seem at times almost like documentaries—is this not the definition of neorealism, of humanism? Yet few directors appear so moody, so emphatically interested in loneliness rather than, say, the anchor of the three-act plot-and thus modernist.

This is the achievement of the Taiwanese New Wave—the synthesis of humanism and modernism. Tsai could wear either of these categories like a hat, but—with his meditative long takes, all the judgment molted off—perhaps a more accurate adjective would be “Buddhist.” More than anything else, his films resemble meditation exercises in which we are forced to look at something until our eyes have been roused to wake up. Sight is meditative, detached, and soulful. And it is the soul, the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Monty wrote, rather than the brain that sees. Tsai wants looking to become unbearable: Vive L'Amour and Goodbye, Dragon Inn end with famously severe long takes, the latter (an almost five-minute shot of an empty theater) severe for its lack of emotional content, the former (Yang Kuei-mei crying for a little bit short of forever) for its surplus; The River ends with a similarly shocking scene. Ironically, although few directors are as interested in the purely private moments of his characters, Tsai's films improve in a packed theater—they become funnier and more tragic, detaining us while we endure Xiao-kang's most secret emotions surrounded by crowds of people.

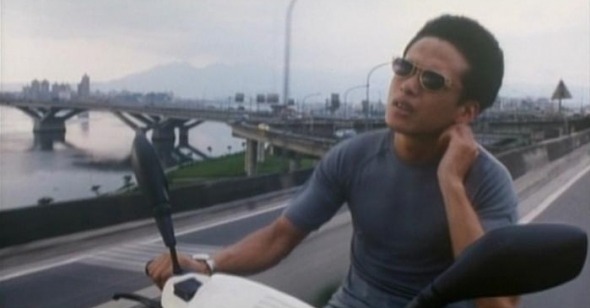

Out of Tsai's six full-length films, The River is his third and acts as a fulcrum with which he weighs the twin poles of his filmmaking. His first three films—Rebels of the Neon God, Vive L'Amour, and The River—have stories: Tsai is interested in watching people and the events they latch themselves onto. The River is Tsai Ming-liang's least Tsai Ming-liang movie because it is packed with more extras, outdoor shots, highways, and motorbikes, more cameos, than his other films combined. It is as if after this, he could only top himself by reduction. Tsai's next three films—The Hole, What Time Is It There?, and Goodbye, Dragon Inn—appear much more fascinated with watching watching itself. These are phenomenological films. Goodbye, Dragon Inn, a movie about watching movies, begins with a shot of the back of Tsai's head as he watches a movie. (What Time Is It There? and The Skywalk Is Gone also have us watch Lee Kang-sheng and Chen Shiang-chyi gazing endlessly at flickering electric light.) After The River, the stories evaporate; Tsai's narratives become ambient. After The River, the cinematography blushes, turns obviously beautiful, all the stucco walls and awkward alleyways glowing as though lit from within.

This kind of metaphysical filmmaking culminates in Goodbye, Dragon Inn, which functions as a sort of tender opposite of Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc. Chen Shiang-chyi's hobbled movie ticketeer is liberated by space rather than imprisoned within it; unlike Joan of Arc, she wants to be provoked by the man in her life and is graceful not because she is a saint but because she is an imperfect person. The shot of her gazing at the comparatively mobile King Hu heroine could be the most elegant image of contemporary film. An emptied-out film of wandering and rundown luminous space, Goodbye, Dragon Inn is an inverted twin to The River—suggestive rather than worldly, curious rather than deliberate, mystical rather than contingent—and maybe Tsai's best film.