Mightier than the Sword

Bedatri D. Choudhury on Legally Blonde

Back around 2001, when a family member returned to India from a trip to the U.S., I was gifted a pink plastic pen with a fluffy, furry, glittery topper. I was told it was all the rage with American girls of my approximate age after the release of Legally Blonde. With its glistening, plastic body and soft head, the pen seemed too pretty to be put to use—and too ridiculous to be practical in my Indian middle school. It remains somewhere on the writing desk back in my parents’ home in Calcutta.

“Too ridiculous to be practical” is something that can be said—by common perceptions of ridiculousness and practicality—of the film’s protagonist, Elle Woods (Reese Witherspoon), her femininity, and pretty much everything she owns and thinks. Elle is always wearing something pink and/or glittery, and very early in its runtime, the film tells us that her greatest talent is perhaps her ability to spot a “last season” dress at a clothing store—she refuses to pay full price for an old gown when the shopkeeper assumes her to be a “dumb blonde with daddy’s plastic.” She is the president of her Californian Delta Nu sorority and a former homecoming queen, someone whose performance of femininity is always so heightened that she is deemed too “impractical” to be taken seriously within the “real” world.

The first in-focus shot in Legally Blonde is that of a tortoise shell hairbrush running through Woods’s long, blonde hair. From there, it’s a cornucopia of glittery material objects filling up the screen: a pink sequined card, a pink razor, a green hairdryer, a bottle of nail polish, all laid against a background of stacked Cosmopolitans and an assortment of other pink furry things. A little less than two minutes into the film, we see two pens with furry toppers in different shades of pink, resting in a penholder on Elle’s desk. Just the kind I was gifted.

As the film begins, Elle and her sorority sisters are certain that her boyfriend, Warner Huntington III (Matthew Davis), is going to propose during dinner that night. The anticlimax comes early as old-moneyed, country-club East-Coaster Warner breaks up with Elle because he has to “marry a Jackie, not a Marilyn” to fuel his senatorial ambitions. He is going to attend Harvard law, his brother recently got engaged to a Vanderbilt, and he “needs someone serious”—something that Elle, with her blonde hair, pink dresses, and high, high heels is not.

Elle gets into Harvard with an intent to win back Warner, and her femininity is so loud and proud that it threatens to puncture the inertness of the campus. The women here—including Warner's new fiancé Vivian Kensington (Selma Blair) who he met in prep school and whose family goes to the same country club—wear powder blue sweaters and pants, sometimes venturing to accessorize with a string of pearls. They wear hairbands that keep their shoulder-length bobs in place while Elle wears her long, wavy blonde hair open.

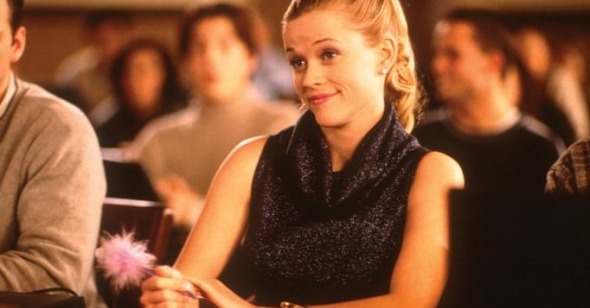

In their quest to seem worthy of the hallowed halls that had kept them out for centuries, the Harvard women must undergo a distinct degendering—it's the only way be taken seriously, even after they've jumped through the same hoops of eligibility as men (a 4.0 GPA) to get in. Women, especially those who perform their gender more loudly and openly, are made to unlearn the virtues of their sexuality and the feminine order of things. Elle’s feminine urge to carry around her pet chihuahua, Bruiser, while strutting in heels, is also embodied in the furry, glittery, “ditzy” pen she carries to her first day at school. The others in her class have laptops while Elle uses her pen to take notes in a tiny heart-shaped pink notebook. She even gets called a “Malibu Barbie” on her first day on campus—a title she probably has no problem with as long as it is said respectfully.

During Elle’s initial few days at Harvard, her outsider status is made clear over and over. In an embarrassing first class, Vivian outsmarts and mocks her jovial sunshiny self. Later, Vivian invites Elle to a party and lies about it being a costume-themed party. Elle, turning up in a furry bunny outfit to a house full of “frigid, constipated” looking preppies, realizes that, no matter how hard she tries, she will never be considered good enough for Warner. In a bid to show him “how valuable Elle Woods can be,” Elle buys into the subdued=respectable equation and ends up at the college bookstore. She purchases a laptop (a bright orange early iMac). The first thing she lets go to “become” a Harvard lawyer is her furry pen. And with it, she discards her outré behavior, straightens her hair, wears cardigans, dark-rimmed glasses, and hats to contain her long blonde mane. The taming of Elle Woods is a public spectacle that shocks and surprises but also breaks down the walls that kept her away from the “Harvard-ness” of things.

Her self-administered desexualizing is meant to aid the heightening of her performance as a “serious” Harvard Law student and, for a while, it works. Elle starts answering questions, winning hypothetical cases in class, and clinches a coveted internship slot in Professor Callahan’s law firm—a possibility Warner had dismissed without giving it any thought. At the firm, Elle works on a murder case defending Brooke Taylor Windham(Ali Larter), a celebrity fitness instructor who also happens to be a Delta Nu sister. When Brooke trusts Elle with her alibi for her husband’s murder, she begs her to keep it a secret; it is a truth that can kill her career instantly. Elle, who will never let down a sister, refuses to divulge any of it to her colleagues and holds on to her feminine, Delta Nu sisterly code of morals (as opposed to the very masculine, fraternal and rigid legal codes) when her colleagues order her to “Screw Sisterhood.”

Even when Elle lets go of the outer signs of her less respectable sorority self, her whole life continues to revolve around the community of women with whom she surrounds herself. Before she takes her LSATs, her best friend gives her a “lucky scrunchy,” and when Warner dumps her, her grief becomes a larger, communal heartbreak. Her quest to get into Harvard Law isn’t a lone battle but a war that Elle fights with her army of sisters. When at Harvard, she teaches her manicurist Paulette Bonafonté (the inimitable Jennifer Coolidge) the “Bend and Snap” routine to seduce her mailman crush with the same seriousness as when confronting her ex-husband to demand custody of their dog. Even Vivian and Elle come to bond over the ways their relationship with Warner limits them and their potential ambitions.

With the considerable toning down of the women’s femininity and their being twisted to fit molds for male approval, women are reduced to submissive roles within the legal profession. You can either get the boss’s coffee, like Vivian, or be propositioned by him, like Elle. Callahan’s sexual harassment of Elle proves to be a pivot point in her career, as it forces her to realize the tight bind of patriarchy. Everyone just seems to be stuck in a fight for respectability they’re destined to lose.

Legally Blonde is an adaptation of Amanda Brown’s 2001 novel of the same name, about Brown’s experiences at Stanford Law. Though directed by Robert Luketic, the film’s script was written by two women, Karen McCullah Lutz and Kirsten Smith. Bracketed by an upper-class whiteness, Legally Blonde’s celebration of femininity and flirtation with feminism predates the toxicity of the “Gaslight Gatekeep Girlboss” avatar that upper-class white feminism has taken today. It is, in fact, a conscious distancing from that pantsuit world and an urge to not give up small pleasures like our furry pens that are a part of our core beings. Going against the grain of a professional world where one is constantly told to “grow up,” Legally Blonde asks us to hold on to the whimsies of our girlhoods and the lessons they teach us. The pen—and the reclamation of everything associated with it—thereby becomes a symbol of resistance against patriarchal co-option, and a reminder to hark back to the sisterhoods we think we have outgrown.

After being hired by Brooke, Elle shows up in the courtroom wearing a V-necked, velvet, candy-pink dress—striking amidst the sea of black suits. She is back to wearing shiny heels with rhinestones and carrying a pink satin handbag for Bruiser. The loose curls in her head of blonde hair, too, are back. In short, she reclaims every sign of femininity she had sacrificed at the altar of serious respectability. Propping herself up on the more “informal” networks of female friendships (as opposed to the harsh hierarchy of men in law firms and court rooms), Elle reclaims the confidence that lies in her old, feminine ways. Her climactic debut courtroom proceeding, in which Paulette and her sorority sisters from college turn up to cheer her on, becomes an unabashed spectacle of her “feminine” knowledge. She helps acquit Brooke by reminding her stepdaughter, Chutney, that one just doesn’t wet their hair 24 hours after getting a perm because it risks deactivating the ammonium thioglycolate: a “cardinal rule” that eventually leads to Chutney’s confession of killing her father accidentally and Elle’s victory in the case.

Legally Blonde dramatizes that women do not have to derive power through the social mobility of marriage. It teaches them to be self-sufficient as long as their conventional, “fun” femininity remains untouched by the realm of a more serious radical feminism, typified by Elle’s classmates. Vivian and Elle, both brilliant (and white and rich) women, for a while draw their power from dating Warner instead of realizing the immense power their privilege and talent afford them. Elle goes back to her performance of hyper femininity, and sees a life beyond marriage, but one of her big wins at the end of the film is the fact that she will be marrying the white, male lawyer—a man whose respect she doesn’t need to work hard to command.

In her valedictorian graduation speech, Elle rewrites the Aristotelian argument, “Law is reason, free from passion,” and makes an argument for passion being one of the keystones of practicing law. This ending rejoices in femininity and the need to bring down the rigidity of traditionally masculine spaces. It’s a kind of rewriting that might be accomplished with the flourish of a furry pen, rather than the sterile tapping on an iMac. As a person who grew up wielding one of those furry things, I am reminded by Legally Blonde of all the glittery objects that I eventually gave up in pursuit of respectability, not knowing that those, too, could be weapons in reclaiming our world from the dispassionate, gray-haired men who strip everything of its pink.