Every Halloween, we present a week’s worth of perfect holiday programming.

First Night:

The Witch

There is a witch. She exists, as plain and bald as the title. Though the characters’ disbelief of her existence is the crux of the film, there are few ambiguities here: we see her early, hunched and naked and involved in a horrifying but vague ritual. She is both flesh and blood and an abstract, metaphorical figure, embodying the deepest fears of the people forging a land that’s depicted as less a hopeful country-to-be than a grim forest primeval. Following a great tradition stretching from nineteenth-century American literature to twenty-first century horror filmmaking, from Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” and Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” to The Blair Witch Project and The Village, the terror of the unknown resides in the woods, a place beyond the borders of the ostensibly civilized world. In Robert Eggers’s The Witch, however, this world is so new that the boundaries between the civilized world and the wilderness are more porous. These puritans—represented by a single family recently arrived on our shores from England—have barely settled. Their environment is dark, cruel, and fetid, a small, ramshackle farmstead surrounded on all sides by deep, dark trees and always overcast by a gloomy, forbidding sky, a constant nightmare from which the family can never awaken.

The Witch is set to open officially in early 2016, but it’s impossible not to include this Sundance and Toronto film festival standout in this year’s edition of our annual Great Pumpkins series. Hope for the future of American horror cinema resides in a film that has returned to the past, all the way back to the genre’s primal, literary roots. In “The Hollow of the Three Hills,” Hawthorne writes about “those strange old times, when fantastic dreams and madmen's reveries were realized among the actual circumstances of life.” Hawthorne’s tale, which paints a short but vivid sketch of the occult in early America, embodied in a “withered hag” conducting an unheavenly rite with a wayward young maiden in a lonely mountain basin not a few miles from the world of godly men, exemplifies what makes Eggers’s film such an effective piece of regional horror. In these early stories, Hawthorne was creating a new national literature. His stories both reveled in and feared nature; viewed the American experiment itself as both worthy and dubious; extended from and critiqued its inhabitants’ puritan ideals and philosophies; and painted these people as given to crippling bouts of irrational paranoia and faith-based hysteria while also occasionally intimating, via the evocation of a supernatural world existing alongside our own, that perhaps some of these fears were grounded in something palpable and real. Eggers’s film carries on this Hawthorne tradition, creating a narrative in which a family’s suspicion and paranoia leads them to violently turn against one another, while at the same time confirming that the corrupting, demonic object of their fears in fact exists. It’s like a cautionary bedtime story told to seventeenth-century American children by cruel parents tucking them in at night as the wind howls outside the door.

Yet for those who might consider this old-fashioned, rigorously unenlightened work of Puritanical horror somehow conservative (one festivalgoer used the dreaded “reactionary” to describe it in my presence), keep in mind that there’s a sly perspective at work in Eggers’s film, one that only makes itself clear in its elevating final passage. First we must get hip-deep in the emotional and physical morass of living in 1630s New England, which Eggers paints as a state of mind. Each shot from cinematographer Jarin Blaschke is awash with a grayish blue autumn chill that overlays the film with the sense of a slowly gathering storm. We barely have met our pilgrim family—sturdy patriarch William (Ralph Ineson), hardened mother Katharine (Kate Dickie), and their children—before they are already thrown into doubt and turmoil. The youngest of their five, an infant, suddenly disappears during a disturbing and swift game of peek-a-boo with her older sister, and these already terrified, distrusting, and profoundly religious folk know in their hearts that the child was spirited away into the woods by evil forces. Thanks to a fragmented, dreamlike early interlude taking us inside the witch’s lair somewhere in the dank dark of the forest—a masterfully eerie bit of suggestive horror reminiscent of Benjamin Christensen’s primitive 1922 Danish silent Häxan, still a cornerstone of occult filmmaking—it’s hard to doubt them. At the same time, Eggers isn't interested in absolutes. The fact of evil’s existence—and in this case its snarling, nightmarish, fleshly manifestation—doesn’t make these flawed humans justified in their response, which is to turn against one another, fearing that the devil has infected all of them, especially, once the finger-pointing starts to fly, cherubic eldest daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy). Imagine Arthur Miller’s The Crucible recast as a work of supernatural horror, with the fantastical elements somehow not negating the central thesis: The Witch is unsettling for being both an unforgiving sociological study of humans in crisis and a confirmation of the fears that lead us to hurt each other.

Save for the hair-raising presence of one sinister goat, forebodingly named Black Phillip, this is a drama of human interaction, of people so concerned with the state of their souls that they disregard the delicate matter of their flesh. The more time we spend with this family in their isolated home, the smaller their world seems, as though the walls are closing in around them. This is a deliberately paced film, of slow zooms, of camera drifts, of tortured silences. Eggers has said he was as inspired by the work of Ingmar Bergman as more obvious reference points like The Shining, and one can feel a debt to the Swedish master throughout, the film’s anguished battles of body and spirit set in claustrophobic spaces recalling such titles as The Silence, Persona, and Hour of the Wolf. Of course Bergman never closed a film with such an ecstatic confirmation of the presence of the supernatural as Eggers does here. Nevertheless, any Bergman lover might probably appreciate this witty and subversive climax, which provocatively points to a possible escape from the terrors of puritanical Americana. —MK

Second Night:

The Hound of the Baskervilles

Serialized from 1901–1902, The Hound of the Baskervilles is the most horror-like of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes mysteries, revolving as it does around a monster in the form of a seemingly supernatural dog with a specific family kill list. It also favors atmosphere over analysis and legwork over contemplation more than most Holmes tales. That atmosphere is provided by the setting on Dartmoor in England’s West Country, a place of unforgiving cliffs and deadly sucking mires (and much natural floral and faunal beauty) that could feasibly house a demonic hound. Baskervilles is also unique in that Holmes is conspicuously absent for much of it, apparently conducting unrelated business in London while ceding the story’s duties about the moor to Dr. Watson.

It makes sense, then, that the novel would be adapted, in 1959, for the Hammer Horror studio, and the resulting film is of a piece with other Hammer titles like Dracula (1958) and The Mummy (1959). Enjoyment of it requires an appreciation or at least allowance for Hammer’s unique low-cost theatrics and occasional camp excesses. The modest budget means that the basic formula from 20th Century Fox’s 1939 version with Basil Rathbone, of fog machines and studio sets, returns, though this time in color (a first for any Holmes film), and with a precious few—and very welcome—location scenes under real, grim, moorish skies in Surrey. Flaunting the mere fact of its colorfulness, the film’s theatrical gels provide lurid green splashes of unknown origin, while fire-engine red paint covers an exotically curved dagger used for ritualistic ceremonies unmentioned in the novel. A set piece in a mine and a fraught near-death by creeping tarantula are two other embroideries provided by screenwriter Peter Bryan and director (and Hammer stalwart) Terence Fisher. (For a more faithful, en plein air adaptation, ITV Granada’s 1988 version starring Jeremy Brett is a go-to.)

Fisher’s film lingers on the nasty prologue, in which it’s explained how Hugo Baskerville invited the family curse during the English Civil War when, during a drunken Hellfire Club–esque meeting with his wine-dribbling companions, Hugo was mauled to death by a spectral hound as revenge for terrorizing a captive woman who’d escaped to the moor. The latest casualty is Charles Baskerville, whose nephew Henry (Christopher Lee) is due to arrive in London before traveling to Baskerville Hall on Dartmoor, where he will surely be killed, his doctor tells Holmes and Watson. Holmes masks his fascination in the intrigue, and his taking on of the case, by balking at the idea of a vengeful hell-dog, though in his mind he’s already planning his secret, sneaky trip to the moor, deceiving even Watson (for the greater good).

Peter Cushing, a fervent Doyle fan who would go on to portray Sherlock in sixteen episodes of a 1968 BBC series, is a less deadpan detective than Rathbone or Brett. He’s impishly arrogant, a little feminine, and not shy about playing up the cliché Holmes-isms (sloping pipe, deerstalker, “Elementary, my dear Watson!”). With his knife-like cheekbones and glassy blue eyes, Cushing is mesmerizing, and you miss him when he’s gone, though his absence is foreshortened in this adaptation. He’s physically dwarfed by Lee (monster to Cushing’s doctor in Hammer’s The Curse of Frankenstein), his real life best friend with whom he acted in 23 films. As Watson, André Morell improves upon his 1939 counterpart, Nigel Bruce, bringing the urbane sophistication suited to a trained medical man and conduit-for-genius in place of Bruce’s childlike buffoonery. Watson is in nearly every scene, and Morell’s gravity offsets some of Fisher and the production design’s gaudier indulgences.

John Le Mesurier’s butler Barrymore, too, is a case of Hammer downplaying; he’s portrayed as a sinister, foreign-seeming suspect in Fox’s version, while he’s always sympathetic here. As the Baskerville’s doctor, Mortimer, beetle-browed Francis de Wolff has a literally sweaty, Alfred Molina quality. The novel’s comic relief character, Frankland, is turned from a plain local crank to a bishop in this version, his role expanded and handled by trusty, mole-faced Miles Malleson, a familiar face from Ealing comedies and dozens of other films, including previous Pumpkin Dead of Night (“Just room for one inside, sir!”). The female lead, Marla Landi, is given some weird and affecting scenes with Lee in which her hitting and scratching lead suddenly to kisses. While in the novel Miss Stapleton is a wife masquerading as a sister to the main antagonist, here she’s his wrathful daughter, and Fisher, in the vein of Howard Hughes or American counterpart Roger Corman, shoots her as a lusty, dangerous sex object. Like most of the film’s choices, it feels natural here, and the result is a dreamlike mood piece of gurgling swamps, the looming castle, and the mysterious moor, kept earthbound by Watson’s pragmatism and Holmes’s genius. It’s exactly what you’d want in an intersection of Doyle and Hammer. —JS

Third Night:

Two by John Carpenter

In the Mouth of Madness

John Carpenter excels at making movies where things are not what they seem. Think of the shape-shifting alien of The Thing (1982), or They Live (1988), in which a painstakingly fabricated reality gets unraveled one good, hard look at a time. These themes of duplicity and image manipulation are easily deconstructed by critics, who have speculated that they express the director’s self-reflexive side; the question is why anybody would bother writing (or reading) an additional auteurist analysis when the guy went and made In the Mouth of Madness (1995)—a movie that Kent Jones described as being set in “a world seen through long lenses [that] keeps ripping off its cheap surfaces to reveal the cheap surfaces underneath.”

“Ripped-off” and “cheap” are the operative terms here. Like most of his late-career output, In the Mouth of Madness is conspicuously thrifty, and its screenplay by Michael De Luca shamelessly riffs (and lifts) from H. P. Lovecraft, whose ancient, gigantic, extradimensional antagonists are revealed to be the villains of the piece. These creatures get rendered in analog, animatronic glory, but their front man is a human, the hack horror writer Sutter Cane (Jurgen Prochnow), a Stephen King stand-in whose best-selling success is the by-product of a Faustian bargain. In a few short, decisive strokes, the film collapses the distance between two American genre-lit titans; King is of course an avowed fan of Lovecraft, and has written pastiches of his style, but Carpenter and De Luca also give the younger author his due as a pop-apocalyptic visionary. “They’re making a movie next month,” purrs Prochnow as his plan comes together: the end of the world as we know it as the last word in multimedia branding.

In addition to its satirical thrust, In the Mouth of Madness is widely regarded as Carpenter’s last credibly creepy movie, and there are a few genuinely skillful set pieces nestled in amidst the dreck; my favorite is the early slow-burner where insurance investigator John Trent (Sam Neill) is approached by a crazed, axe-wielding Sutter Cane fan in broad daylight at a swanky restaurant, his slow, zombie-like advance from the other side of the street glimpsed through a giant window frame—further evidence in the case for Carpenter as widescreen maestro. Elsewhere, the shocks are more staccato, as when Trent snaps out of a fearsome hallucination only to find that the bogeyman is sitting next to him on the couch. It’s a shameless jump scare, perfectly executed.

Neill’s performance as the designated Lovecraftian stooge—the sane man driven batty by the realization of what’s really going on around him—is excellent; he cuts a formidable figure in a loony-bin prologue that achieves true EC Comics grandeur. Trent’s arc from seen-it-all cynic to hysterical doomsayer recalls Roddy Piper’s Nada in They Live, and the two films have rhyming endings as well, with the ghoulish TV transmission of the earlier film efficiently recycled into a satanic rep house screening—shot at the late, lamented Eglinton Theatre in Toronto (where I happened to get married).

It may be that In the Mouth of Madness is more jokey than scary, perhaps a sign that Carpenter’s heart isn’t really in the material; it’s a lighter entertainment than The Thing, for instance. But the opening credits montage of a best-seller being churned out by massive printing presses projects a wariness of industry and conformity—just like the overture in Carpenter’s 1983 adaptation of the King-penned Christine—and thus hints at something more chilling than mere slimy monsters. The final scene’s reveal that the film-within-the-film of In the Mouth of Madness, which is ultimately the delivery device for the death of humanity, has been “directed by John Carpenter,” is meant as a self-implicating joke, and it’s perfectly okay on that score. But I always preferred this little stinger, buried deep within the end credits, after the requisite bit about the American Humane Society: “Human interaction was monitored by the Inter-Planetary Psychiatric Association. The body count was high, the casualties are heavy.”

Very funny, John Carpenter. —AN

“Hair”

Vanity and silliness are inextricable. Chaucer’s Absolom from The Miller’s Tale is said to possess a head of hair “strouted as a fanne large and brode” and is “clad ful smal and properly,” but he still ends up with a fart in his face. The impish tone of John Carpenter and Tobe Hooper's overlooked 1993 made-for-TV portmanteau Body Bags is underlined by its panoply of winking horror auteur cameos (Roger Corman, Wes Craven, Sam Raimi) and a deliriously macabre M.C. turn by Carpenter himself as a Lon-Chaney-phantom-nosed mortician with a less-than-respectful attitude to the corpses in his care. Its middle segment, “Hair,” directed by Carpenter, stars Stacy Keach as an aging playboy with a thinning top and a girlfriend half his age and body weight (Sheena Easton, who by cruel contrast has magnificent hair). It is palpably the silliest of the three stories (the others concern an escaped serial killer and a blinded baseball star), yet conceals within its exquisite campery a mordant satire on vanity—and a unique strain of body horror, wherein the physical degradation on display has an alarmingly universal flavor.

Once an emotionally gelded Keach has exhausted all the hilarious tonsorial replacement options available (as he exits an expensive salon with a ludicrous beehive, watch out for the slo-mo shot of an Afghan hound flouncing down the street to rub Keach’s nose in it), his supportive girlfriend finally cracks and leaves, exasperated by his stubbornly crippling self-consciousness. “Oh, sure. Walk out on the bald guy!” Keach shouts after her. His last hope is a miracle follicle formula, peddled by (alarm bells!) horror perennial David Warner, sporting a lavish Tony-Blair-circa-1996 bouffant. The “protein mix” (“What’s in it?” “It’s patent”) works like a dream, cultivating a luscious mane for Keach overnight. He has become Samson: women now stop and gawp at him wherever he goes.

The horror payoff to this story is revolting. The “hair” is made up of tiny alien worm-like organisms, which begin to take control of Keach's head, face, and mucous membranes, rendering him a Neanderthal mess. We are used to seeing body horror represent planetary invasion (The Thing; Invasion of the Body Snatchers) evolution (The Fly; Tetsuo), and violation (Alien; Trouble Every Day), but rarely the quotidian fear of getting older. The original literary meaning of the word vanity was futility, and appropriately the deeper horror here is down to Keach’s own body, and in his character’s inability to grasp the utter pointlessness of everything he tries to do about it. Anyone who has suffered from it—or has spent any time by the mirrors in a male gymnasium changing room—will know only too well the special stomach-knotting horror of the prospect of losing one’s hair, and the futility of the available solutions. Even Keach’s rich locks, when they arrive, make him look laughably grotesque. Ten minutes of WWF are enough to conclude that middle-aged men simply can’t pull off long hair and should never try. In a delicious finish, after a devastating slow zoom on Keach’s Chewbaccified face, the segment ends and cuts away to the director Carpenter, proud possessor of one of the most terrifying bald/mullet monstrosities in the history of cinema. —JA

Fourth Night:

Ringu

Enough time has passed that it’s perhaps worth revisiting the films of the J-Horror craze from the turn of the millennium. It seems clear in the rear-view mirror that many of these films savvily exploited Y2K fears, while wedding them to traditional horror tropes and devices. Today, we can barely synopsize some of these movies without giggling: Takashi Miike’s 2003 One Missed Call, about the evil of cell phones; Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s 2001 Pulse, concerning ghosts that come through the Internet (the sound of dial-up is the sound of death!); and Hideo Nakata’s 1998 Ringu, about a cursed . . . VHS tape. That these films are actually terrifying says more about the classicism of their content rather than the clunky delivery systems. Pulse, especially, is a beautiful piece of craftsmanship, a melancholy tale of apocalypse-by-loneliness that mitigates the essential alarmism of its conceit—the online world is fatally disconnecting us from one another—by enshrouding itself in chilling atmosphere and foregoing shock effects in favor of shadowy, unsettling imagery that slowly burrows into your skull. Ringu is less elegant but perhaps even more frightening, a genuine hair-raiser in which ghosts travel through technology not to bring fatal misery but paralyzing fear.

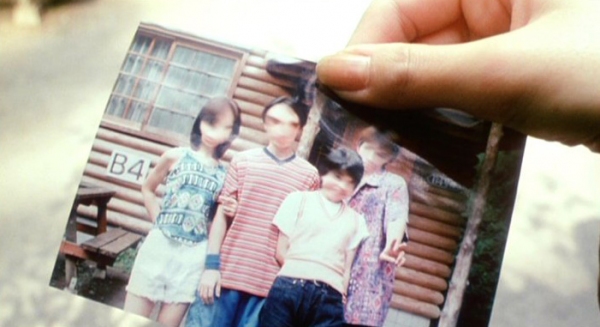

Ringu—in which a divorced mother has seven days to stop herself and her young son from becoming the victims of a deadly curse by unlocking the mystery behind the bootlegged videotape that carries it—has so many singularly arresting scare scenes that of course Hollywood had to come along and steal them wholesale. American viewers are undoubtedly more aware of Gore Verbinski’s 2002 hit remake for DreamWorks, The Ring, starring Naomi Watts; the success of that film only proves the sturdiness of the original conceit and the primal pull of its imagery. Its most famous image, of a medusa-like wraith, long black hair obscuring her face as she crawls, then shambles, toward the camera, getting fearfully closer and closer to her terrified victim and to us, has become iconic, a figure that stands in for an entire subgenre of cinema. That this soaking, stringy-haired being without fingernails has literally emerged from the television into the living room makes her seem vivid, horribly hyperreal. The remake’s rendition of this monster missed the point: by adding flashes of black and white television static and fuzz to digitally distort and desaturate her figure, it made her a less tangible, fleshy being. A film still very much situated in the era of tactile physical media, Ringu remains powerful not despite but because of its use of videotapes as carriers of evil. Until proven wrong by a truly haunting film about ghosts that live in the Cloud, I cannot imagine that anything could be scarier than a movie about clunky possessed objects. Technology—and as a result, time—moves so fast now that Ringu, with its scenes of people agonizing over the images of a video plagued with bad tracking, already feels pleasantly aged, offering the air of a classic MR James story of curious book scholars poring over musty, cursed texts in gloomily lit church sacristies.

By combining elements of the moralizing pass-it-along curse narrative (in use from James’s 1911 story “Casting the Runes” to Sam Raimi’s 2009 film Drag Me to Hell to this year’s It Follows) and the Medusa myth (just one look is all it takes to kill you), Ringu could seem like a barrage of horror’s greatest hits, but it feels wholly its own beast. I can recall first watching the film in 2001 during Film Society of Lincoln Center’s survey of new Japanese horror films and feeling like I had never seen anything quite like it: more than just effective, it was invasively scary. Like the best horror films, it felt like a grasping hand from beyond the grave, beckoning the viewer into oblivion. All of its frights contribute to an overall sense of impending doom: the distorted and blurred faces in photographs of people after they’ve been marked; the frozen, gaping maws and bulging eyes of those who have met their fates; the trembling, rattling score, occasionally interrupted by shrieking strings.

Then there’s the video itself, a disconcertingly brief series of disjointed scenes that have the air of a particularly foreboding experimental short: clouds passing over a full moon; the reflection of a woman in a circular mirror combing her long hair and looking over her shoulder; a strange, impossibly angled reverse shot of the figure she sees staring back, in another mirror; contorting and writhing Japanese writing; perhaps worst of all, a man standing stock-still, his head covered in a white towel or blanket, his hand pointing at something offscreen. Finally there’s a static shot of a well, from a distance, poking up out of the ground. It’s where the ghost’s secrets are buried, of course, and in the first of the film’s two climaxes, our heroine ends up at the bottom of this murky cylinder, her hands searching through black water for the corpse that might help reverse the curse. Of course her hand comes back to the water’s dirty surface with a fistful of soaking wet hair. Ringu is a ghost story, but Nakata wants to scare you with something you can reach out and touch. —MK

Fifth Night:

The Visit

Growing old is scary business, and must seem especially so to the very young, to whom aging is unfathomable. What does a child know of arthritis, dementia, incontinence?

This fear of the unknown lies at the core of M. Night Shyamalan’s low-budget 2015 creeper The Visit, which follows teenaged siblings Becca (Olivia DeJonge) and Tyler (Ed Oxenbould) on a winter trip to visit the grandparents they’ve never met. Their mother, played by Kathryn Hahn, left home ages ago in the wake of some never-discussed scandal and hasn’t seen them at all in the intervening decade and a half or so, and she sends her children off alone at her parents’ behest. At first, Nana (Deanna Dunagan) and Pop Pop (Peter McRobbie) seem picture-perfect—doting, kindly, a little daft, with yummy baked goods at the ready. However, they’re barely beginning to all get reacquainted before things start seeming odd: the kids hear strange banging and scraping in the night; Pop Pop wanders zombie-like to a remote shed, ignoring their entreaties to come play, and later violently assaults a random passerby; Nana, for her part, seems to spend more and more time staring off into space—when she isn’t asking Becca to climb all the way into the oven to help clean it.

A sense of menace and danger mounts over the course of their visit, but it’s all easily explained away by actual physical ailments. So, that banging and scraping in the night is merely Nana “sundowning,” a form of night terror that affects the elderly. Pop Pop’s trips to the shed turn out to be shameful ones: to hide and swap out soiled diapers. For the children, who know nothing of the elderly, this all seems quite plausible. Yet things still seem off. A game of tag in the small crawlspace under the house takes a dark turn when Nana joins in unannounced, on all fours, wild gray hair flying and sinewy limbs poking out from her dress, like some sort of deranged banshee. Shyamalan pitches this scene somewhere between hilarity and terror—you might wonder what the hell this woman is doing crawling around and growling as you watch through your fingers, hoping to avoid seeing her manic face in close-up.

The sequence’s tension is expertly dissipated: after the three leave the crawlspace, Nana walks back into the house, one sagging buttock left uncovered by her romp in the dirt, a banshee no longer, just an old lady. Cheeky. Everything we see in The Visit is filtered through the perspectives of Becca and Tyler, all of the images filmed for a documentary Becca is making about their trip. The ethics and practices of nonfiction filmmaking are much under discussion: Becca initially refuses to place a hidden camera in the living room at night to film what actually happens when Nana sundowns, as the subject will have been filmed unawares; the girl regularly asks one of the other characters to repeat an action so she can get a better angle. What’s perhaps most frightening about The Visit might be that, even though this faux-documentary frame is handled with a winking nonchalance, it exhibits a more complete understanding of the essential questions and decisions behind nonfiction filmmaking than many working film critics are able to offer. (This all is certainly handled better than in this year’s othernarrative examination of documentary ethics, the ham-handed While We’re Young as well.)

Though much of The Visit is skillfully executed and very often jolt-inducing—Shyamalan manages to work his penchant for long takes and off-kilter framing into the nonfiction apparatus without skipping much of a beat—it’s still quite a dumb thing. Shyamalan’s comedy has always leaned to the broad Catskills variety, and this is a film filled with groaners (see Taylor’s attempts at freestyle rapping). And by now you’ll know to expect some kind of twist, and The Visit doesn’t disappoint. But what’s also maintained here is Shyamalan’s acumen for locating underneath the surface of all of his fantastical scenarios—kids who can see ghosts, dads who get superpowers, pending alien invasions, villagers besieged by monsters, nymphs in pools, trees gone mad, mystical martial arts children, father-son lost world excursions—buried emotions, hurt feelings, loss, fear, pain, and loneliness. Very human stuff for often otherworldly films. In this sense, he has always been, and remains, scarily consistent. —JR

Sixth Night:

Nosferatu the Vampyre

Out of the more than sixty shorts and features in his filmography, Werner Herzog has only once directed a horror movie. But what a horror movie it is. In 1979’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht) there are creaking doors, sharp contrasts between shadow and light, the cries of wolves mingled with howling wind, several cemetery scenes, and various monologues that warn of vampires, from the ravings of Renfield (Roland Topor, cast by Herzog for his shrill, mad cackle) to the fearsome premonitions of Lucy (an ethereal Isabelle Adjani). There are also jolts. Adjani rises to the role of damsel in distress, letting out startling screams of fear as she awakens from nightmares: of a bat gliding through the night air in slow motion, and visions of her husband, Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz), succumbing to the rat-like fangs of Count Dracula, as portrayed by a moaning, tortured Klaus Kinski. This is Herzog relishing the tropes of the horror genre.

Herzog based his rendition on F. W. Murnau’s 1922 silent classic Nosferatu, which he called “the best German film ever.” Herzog’s intention was not to best Murnau but to learn from him. As part of the New German Cinema of the 1970s, Herzog felt a responsibility to offer a connection between his generation of filmmakers and those who directed during the Weimar era, before Nazism tainted the nation’s film canon. In a documentary on the making of this film, Herzog said, “I think it is necessary since we are a fatherless generation to have some sort of a continuity in film history . . . For the first time, I do a genre film, and I follow the laws of the genre, and that of course is a difficulty and a challenge for me. But more than anything else, it is a question of establishing a link between the great legitimate German cinema of the twenties.”

Like the long, stark shadows that defined German expressionist cinema, a sense of looming catastrophic inevitability haunts Herzog’s Nosferatu. There is no expectation for anything less than tragedy as these characters lumber inexorably toward their fates. The sense of doom starts with the film’s opening title sequence, which unfolds as a camera slowly pans over stacks of mummified remains. After the sequence cuts to the languorous slow motion film of a bat in flight, Lucy springs upright in bed to open her mouth, offering only a piercing shriek. Looming misfortune is also creepily heralded in the warning Jonathan receives from Renfield, his boss in real estate, later revealed as Dracula’s enslaved familiar. He has a job for Jonathan: take the deed for a new property to Dracula, so he might sign it and move from his castle in Transylvania and into a decrepit mansion in their city of Wismar.

For all its rigorous following of genre conventions, Herzog’s Nosferatu also offers signature characteristics of its filmmaker’s ethos, as displayed in his other films from that era. Here, a director with a penchant for realism and nonfiction, adapts well to the rules of the spooky horror movie without compromising his style. For example, Herzog was well known for employing nonactors during this period, and a group of gypsies who greet Harker upon his arrival in Transylvania are all played by real gypsies, their weary superstitious stares giving the film a peculiar authenticity.

As in much of Herzog’s seventies and eighties films, the score is by Florian Fricke (a.k.a Popol Vuh), whose ornate and exotic music has always exquisitely accompanied Herzog’s eye for nature. From weather to light to landscape, the intricate and dynamic music of Fricke adapts to the extreme contrasts of light and dark, as Harker journeys from the warmth of home to the chill of a castle in ruin. Harker’s journey to meet the count is captured in an array of tones and melodies in a theme called “Brothers of Darkness, Sons of Light.” A bright, pastoral guitar melody mixes with droning sitar as Harker crosses open meadows and ambles through a small village, while a chilling Gregorian chant section, which melds with sustained horns and strings, accompanies his climb across a misty mountain to the decrepit stronghold of the vampire.

Nosferatu also marked the second of a series of Herzog films led by Kinski, who brings a striking amount of pathos to the vampire. Kinski’s Dracula is tired. He’s done with living. The curse of immortality weighs heavy. He speaks in weary, wasted groans. The howls of wolves give him pause as he hosts Jonathan with dinner: “Listen … listen,” he says blearily, “the children of the night make their music.” But the thrill of this “music” is long gone.

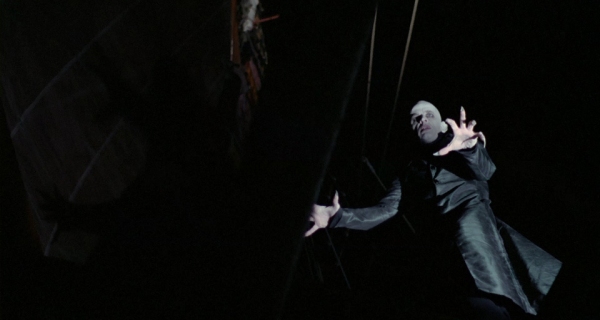

When Dracula and Lucy first meet, toward the end of Nosferatu, the film most strikingly presents its thesis of Eros and Thanatos. As Lucy lets down her hair in front of a vanity, the door creaks open by itself. Dracula enters as only a clawed shadow in Lucy’s mirror before he creeps to the side of the mirror to appear in physical form. As they stand off, she with a crucifix around her neck, he with his reaching, razor-like fingernails, they debate love, death, and the eternal. “Dying is cruelty against the unsuspecting, but death is not everything,” croaks the vampire. “It’s more cruel not to be able to die. I wish I could partake of the love which is between you and Jonathan.”

“No one in this world,” says a wide-eyed Lucy, “not even God, can touch that.” It’s stagey, but speaks to a primal fear of living a life unloved. What is Nosferatu after all but a man searching to fill the unfillable void of desire: a horrific image of the emptiness of life. —HM

Seventh Night:

Carrie

A revenge story that purposely denies viewers’ satisfaction, Carrie remains unique in the annals of horror. Brian De Palma’s film is a work of enormous empathy—for its nasty villains, its ambiguous heroes, and of course its central figure, one of the most fragile monsters in all of cinema. As embodied by Sissy Spacek, Carrie White is a strange creature, but one that we want to protect—from her bullying high school peers, from thoughtless teachers and principals, and most of all from her deranged, religious zealot mother. With all these forces unwittingly collaborating to relentlessly dehumanize her, Carrie never had a chance. Nevertheless, De Palma’s virtuosic, emotionally charged adaptation of Stephen King’s debut novel teases the viewer into thinking that she just might escape her wretched existence, if she can just be accepted. The film stays both close to Carrie and at a remove from her, asking viewers to provide the loving care that she never received. When acceptance and love are denied her once and for all, in a public shaming of Grand Guignol proportions—she is doused in a bucket of blood from a freshly slaughtered pig on the stage of the prom after being elected queen—her revenge is as outsized as the nasty joke itself. What results is not the thrill of vengeance, but a tragic, almost Shakespearean denouement in which all humanity—the good, the bad, the nobodies in between—burns to the ground.

A film from the pre–John Hughes era, Carrie was ahead of its time in its naturalistic depiction of high school as a breeding ground for neuroses. Stephen King’s central idea is a good, nasty one, even if it’s always seemed a bit dubious for having come from a male novelist: a teenage girl’s coming of age—literally her menstruation—triggers her latent telekinesis, which grows in power until the climactic torrent of violence. The equation of a young woman’s late-blooming puberty with the uncorking of supernatural powers could be read as inherently offensive, but it’s also in keeping with the genre’s tradition of the female body as a locus of horror. Carrie doesn’t critique this tradition, exactly, but De Palma does make his main character so intensely likable that one would be hard-pressed to side with anyone but her, even when she becomes the image of fiery hell itself. Carrie White is a contradiction, a tremulous, quiet being hiding enormously destructive powers, and Spacek plays her with a carefully modulated intensity. De Palma ensures that just about everyone around her is more of a broad type, all the better to put her humanity in relief: Nancy Allen and John Travolta’s horrible bickering couple Chris and Billy; William Katt’s frizzy fro’d blond all-star Tommy; and of course Piper Laurie’s frothing, St. Bartholomew-loving, Bible-thumper Margaret White, who enjoys beating and humiliating her daughter almost as much as reciting Old Testament passages.

Most horror movies on some level need to make you crave bloody satisfaction, yet Carrie has always seemed too attuned to everyday cruelties and is too invested in its misfit protagonist for one to gain any true pleasure from the nightmarish events that need to happen to precipitate her retribution. De Palma stages the climactic prom sequence as the ne plus ultra of faux-celestial gaudiness (watch that incredible single take that spins in ever escalating circles around Spacek and Katt as they dance and get to know each other) before it devolves into bloody chaos; he makes the glittering world of teenage desire so palpable that we don’t want it to go away. “It’s so beautiful!” says Spacek looking at those chintzy tinfoil stars, and does she ever seem to believe it. Her wide-eyed wonder at finally seeming to have been accepted by her schoolmates is so infectious that one could accuse De Palma of cruelly exploiting Carrie’s momentary happiness, but it’s so desperately vivid and sad and humane; it’s impossible for anyone other than an emotionally attuned person to have made it. Moreover, the film takes great pains to make us care about a great deal of the people who end up as Carrie’s victims, including Betty Buckley’s kindhearted gym teacher Miss Collins; the thanks she gets for trying to help is getting chopped in half by a falling rafter.

Carrie is upsetting and often frightening, but its scares don’t function in the way of a normal horror movie. De Palma doesn’t jolt us with empty shocks—it’s a film about the audience’s uncomfortable identification with the main character. After she is doused in the blood, we want Allen and Travolta’s evil pranksters to be discovered, not the entire graduating class to be flayed, dismembered, and burned alive. Even the killing of her nearly homicidal mother, whom Carrie crucifies with kitchen knives and utensils (including in one sick little joke, a carrot peeler), is wildly unsatisfying, as Spacek’s horrified reaction and De Palma’s patient camera make her death more of an inevitable misfortune than a happy ending. Carrie is one of those movies that we return to because De Palma’s technique is so assured, but it’s always a difficult film to sit through: his characters, and our interactions with them, are so fragile. Every time I see it I hope the ending might change—if I wish hard enough. Maybe this time that the bucket of blood will miss her completely. Maybe the failed prank will be laughed off by the roomful of teenagers; they know better, they finally realize that Carrie is, after all, one of their own. This time, Carrie will not have to become a monster at all; she will go home with a prom queen crown and a smile on her face. Then again, the idea of Carrie as normal, as one of us, just another dull human, is perhaps the scariest thought of all. —MK