All Lit Up

Jeff Reichert on One from the Heart

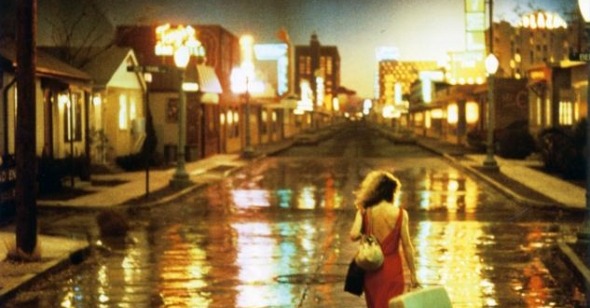

After the bloated, storied, never-far-from-catastrophe production of beleaguered war epic Apocalypse Now, it shouldn’t have come as a surprise that Francis Ford Coppola retreated into the safe confines of his Zoetrope studios for a more “modest” outing, one that could be made entirely under control, and not at the whims of nature, unstable political situations, or suddenly overweight actors. Of course, this “modest” Vegas-set romantic musical, One from the Heart, swelled just as grossly as its predecessor, from a budget of around two million to one reportedly over twenty-five, all the result of Coppola’s decision to rebuild casinos, large portions of the Sunset Strip, McCarran Airport—the dizzying sense is that he’s transplanted all of Vegas—on the backlot rather than shoot in the city itself; the film’s closing epigraph proudly trumpets this particularly notable bit of directorial hubris in an elegant scripted title card, which reminds audiences: look what I did. During his career heyday, thinking small wasn’t part of Coppola’s vocabulary, and One from the Heart easily ranks on any list of filmmaking egotism gone amok.

One from the Heart bankrupted its creator (Coppola has ruefully joked that he was accepting paying gigs like Jack and The Rainmaker well into the nineties to recoup production debt) and was generally met with confusion and disdain. It’s unlikely anyone expected his four-film run of creativity and ambition in the seventies to crest into the eighties with a Busby Berkeley–inspired fable scored by a growling, muttering Tom Waits and seemingly lit almost entirely with klieg lights saturated with intense reds, blues, greens, and yellows. It’s an otherworldly film, as hallucinatory in its way as Apocalypse Now, and as unconcerned with the niceties of classical narrative. Perhaps after proving his mastery over the straight story with the tensely told Godfather and The Conversation, then pushing at its limiting boundaries with the parallelism of The Godfather: Part II, it was only natural that he dispense with it entirely. Apocalypse Now was widely deemed bonkers and enigmatic in its day. One from the Heart may be even more radical.

As the film starts, live-in lovers Hank (Frederic Forrest) and Frannie (Teri Garr) are set to celebrate their fifth anniversary on the fourth of July, but end up fighting and splitting up instead. The ease with which they slip from argument to lovemaking to fighting again (they promise to stop arguing forever only to storm into the streets minutes later, screaming) suggests an ongoing, cyclical tension. After briefly mourning, both set about to finding the happiness they thought they never had together. Frannie spends an evening on the town with slick wannabe musician Ray (Raul Julia), and plots an escape with him to Bora Bora. Frank runs across young circus performer Leila (Nastassja Kinski) and seduces her in turn. As their respective affairs progress, rational time is completely dispensed with—Coppola seems more than comfortable with jumping from dusk to dawn, sometimes in the space of a single shot—and it's at times unclear whether Hank and Frannie have been apart for one night, several days, or if the concept of a “day” even applies in the heightened unreality of this universe. As their storylines diverge, Coppola employs a host of tricks to cram the erstwhile couple back into the same image: crazy superimpositions, mirrors, bifurcated sets divided by diaphanous curtains, split screens. The visual play reminds at times of the casual disregard Busby Berkeley displayed for the integrity of the photorealistic frame in such films as The Gang’s All Here.

Coppola’s free use of dreamlike superimpositions (especially a sensual dance Leila performs from inside a giant martini glass in Hank’s buzzing, lustful imagination) is remarkable, but his on-set experiments are what make the film an exquisite visual treat. With Vittorio Storaro, Coppola created for One from the Heart some of the most tactile, expressionist lighting schemes ever to grace American cinema. That phrase used by the great cinematographers about “sculpting with light” is made tangible here: as Hank and Frannie fall apart, they’re isolated in the frame by supersaturated colors, and set in relief by swatches of utter darkness. The lights often intensify and dim around them, further isolating select pieces of filmic space, brightening to match the mood of the sequence or cutting out to punctuate a line of dialogue. This constant play with light and the overall indifference to hiding the clearly forced perspectives and faked skylines at the outskirts of his massive constructed sets lends One from the Heart an air of intentional artificiality, yet only serves to put more focus on the very real core of the film: mooky Hank and striving Frannie and their disintegrating love. Why do we care about this pair, when they’ve practically collapsed at the film’s outset? Because Coppola’s carefully heightened our senses through visual manipulation. One from the Heart often looks like the most romantic film ever made.

It’s miraculous that Garr and Forrest can carve out any space at all for Frannie and Hank in and amongst the Coppola’s foregrounded cinematic wizardry, but even in a more simply told iteration of their scenario their breakup and eventual reconciliation would still tug the heart. Passions run high throughout One from the Heart, but, in the end, none more so than Coppola’s for the possibilities of nearly unfettered filmmaking. The operatic sense of light and shadow on display here wouldn’t return as dramatically to his oeuvre until select sequences of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and his more recent black-and-white outing Tetro. The only way Coppola could have taken his production to more extreme limits would have been the removal of gravity entirely. The result is a grand vision, one that could—should—have been held up as an alternative model for daring studio filmmaking rather than being relegated to the film maudit dustbin. That this very traditional, almost conservative vision of romance, dressed up in clever eye-popping layers of artifice failed so dramatically in the early eighties perhaps says, in retrospect, more about the encroaching cynicism of the day than the film itself. A few decades on, it’s clear we should be talking about Coppola’s incredible five-film run.

One from the Heart played July 14 and 15 as part of at Reverse Shot's See It Big series at Museum of the Moving Image.