First Night:

Inferno

This time last year, enervated by the hollow experience of watching The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning and then energized by a late-night viewing of John Carpenter’s lovely and terrifying The Fog, I began a week-long expedition to reclaim horror for myself, with a little help from my friends, of course. Sure, the films we discussed were recommendations to readers, but also ways to revive our own enthusiasm for a film genre that seemed to be either treading water or had descended into empty, gory nonsense. Of course, a year hasn’t made much of a difference. From the derivative insults and camptastic idiocies of Joshua to the useless “verité” of 28 Weeks Later to the tired excess of Robert Rodriguez’s waste-of-space half of Grindhouse, Planet Terror, and, finally, to the granddaddy of all badness, the loathsome, self-congratulatory Hostel Part Two, 2007 hasn’t exactly been a banner year for horror. Sure we had The Last Winter (but for God’s sake, we recommended that last Halloween), the tidy French import Them (but for God’s sake, too tidy!), and Rob Zombie’s expertly ruthless Halloween redo (but for God’s sake, it’s the eighth Michael Myers movie … or something). But two of horror’s essential elements, surprise and the unknown, seem to be in short supply.

These days the gritty, grimy, and handheld seem to be the prized aesthetic virtues of the horror film, and this pretty on-the-nose visual approximation of what “horror” is supposed to be has all but destroyed the possibility of beauty out of the genre. And whatever qualms I’ve had in the past about the nearly pathetic storytelling abilities and barely interested characterizations of Italian horror director Dario Argento seem to be dissipating with each passing year. At this point, I’d sacrifice ten motivationally sound, “realistic” scare machines for just one example of a horror film with the exquisite formal control of Argento in his heyday. The luscious Suspiria is rightfully lauded as his most tightly composed widescreen pleasure, Deep Red may have some of his most memorable death scenes and something nearing an actual protagonist, and Opera certainly remains his most eye-popping, literally and figuratively, yet upon this week’s viewing, Inferno seemed to me to be his most consistently gorgeous—it’s basically an endless series of dazzlingly colored and framed compositions, and it glides from one terrifying set piece to the next with devil-may-care fleetness.

The plot is, of course, a big, sweaty wad of dumb, but in the face of such a carefully crafted hallucination, why bother with such niggling details as coherent story? Meant to be watched late at night, and often through protective fingers, Inferno is the second in Argento’s haphazardly conceived “Three Mothers” trilogy, after Suspiria and before The Mother of Tears, his long-gestating conclusion, which, this year, finally premiered to the usual mix of cheers and chuckles at the Toronto Film Festival. It has something to do with a coven of evil witches who control powerful outposts in Freiburg (Suspiria), Rome, and, in this case, a suspiciously, gorgeously artificial version of New York City. Illuminated by bordello reds and emerald neon greens, this Manhattan is made up of basically a single block, containing a gothic apartment building, and Central Park, realized as a dreamlike composite, shot in Rome with New York skyscrapers superimposed around its perimeters. It’s dazzlingly cheap stuff, and when its lead “characters” skulk and are stalked around its environs, it seems as though it could all tumble into a sea of paper maché and cardboard at any moment.

Perhaps the lack of character is least conspicuous in Inferno because the film foregrounds its own attention to architecture and indeed, that’s where its horror derives from—like if Rosemary’s Baby had foregone its profound psychological terror and instead extended its opening credit sequence to become a visual essay on the Dakota building. Even more so than in its gruesome, creative killings, Inferno locates its fear through hallways, basements, shadows, colors, and crawlspaces. There’s a stunning bit of set design inside a mausoleum-like Roman library, which Argento surveys with a fascinated, lushly rising camera all the way to its disjunctively modern roof, and a truly unforgettable bit in which a regrettably nosy student goes diving into an underground room that’s been completely submerged in water. It’s tense, drawn-out, and paced to necessarily match the slowed-down underwater movements; while there’s a chintzy necessity to the filmmaking (there’s an obvious, if lovable, inability to capture the action from too many angles in such restricted spaces, resulting in limited coverage) this scene gets at the basic, undeniable seriousness with which Argento makes his essentially ridiculous movies. He wants to scare you by showing you things you haven’t seen before, or perhaps couldn’t even have imagined seeing. —Michael Koresky

Second Night:

Cujo

Let’s face it, those of our generation who grew up fascinated by horror movies didn’t spend our impressionable early years mulling over the hidden, sophisticated treasures of Bava, Tourneur, Lang; in fact we might not even have seen a Romero film until we knew it was sanctified as “good for us,” and Cronenberg was still only as effective as his trashy-looking video boxes (that Scanners cover art, with its pulsing, shaking, about-to-explode head was freaky dynamite). For me, horror worked best not due to any clandestine, cult following it may have had, but in its most seemingly relevant form, as a viable mainstream Eighties product. And with no true horror director consistently working within the genre to capture the imagination, the most recognizable “auteur” was obviously Stephen King. Not a director himself (save Maximum Overdrive, his awful 1986 adaptation of his own short story “Trucks”), King nevertheless had a name that lorded over horror in the Eighties, for better (The Shining, with a little help from Kubrick; The Dead Zone, from Cronenberg; Creepshow, from Romero), or for worse (remember Firestarter? how about Silver Bullet?), or for middling but nevertheless iconic (Children of the Corn).

Of course, we grew up, and King’s writing, with its folksy, New England banter and pop culture digressions, seemed increasingly infantile, the lack sophistication in his sentences outweighing his undeniably captivating storytelling abilities. The heyday of King seems a distant memory, dotted as his oeuvre is now by middlebrow male weepies like The Shawshank Redemption and loopy, camp nonsense like Dreamcatcher. Yet his horror movies remain, and none continues to snarl as loudly and viciously as Lewis Teague’s 1983 adaptation of King’s Cujo. Everyone knows the name, but how many remember the movie? Plagued by a Warner Bros. ad campaign in 1983 that refused to reveal the identity of its central villain as “merely” a rabid dog, rather than reliably supernatural, or a serial killer (the poster was just a bloody fence and the tagline reading “Now there’s a new name for terror”), Cujo has always been easily derided for its subject matter. Yet rather than the gore-drenched variation on “When Animals Attack!” that many might assume it to be, Cujo is a surprisingly robust tale of guilt, infidelity, and trauma.

Tense, sad, and cathartic, the sweat-drenched Cujo is also, first and foremost, and without shame, character-driven. This isn’t unnoteworthy for a genre that often simply wants to shuttle viewers from one thrill to the next. Cujo, a massive Saint Bernard and the roaring id of a crumbling Maine family, doesn’t attack the central characters until well over an hour into the film; instead we get expertly plotted build-up, detailing the socioeconomic differences between the middle-class Trentons and the backwoods working-class Cambers. Donna and Vic Trenton are dealing with increasing marriage strains, made the worse by Donna’s affair with the “local stud”; meanwhile, dissatisfied car mechanic Joe seems to have loathed and resented his wife, Charity, for years. Each couple has a son: the snub-nosed adorable Trenton tyke is Tad, who’s scared of monsters in the closet, while the Cambers’ son Brett takes care of his beloved Cujo, shown in the opening sequence being bitten on the nose by a screeching bat. The only connection between the two families is that Joe has done work on Donna’s prone-to-stalling Pinto; it’s only a matter of time before Donna, with Tad in tow, breaks down at the Cambers’ distant outpost.

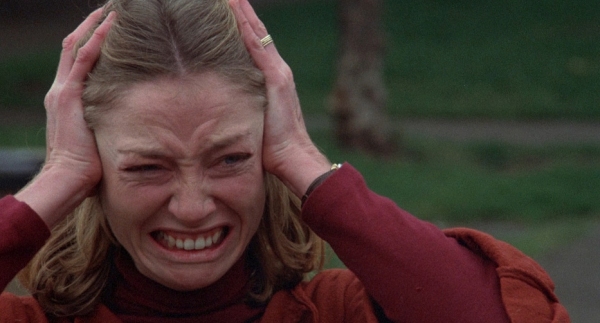

Teague (who also directed the far more tongue-in-cheek Alligator and Cat’s Eye, another King collaboration) crafts his film with direct, effective, mostly unfussy precision (with excellent, merciless editing by The Edge’s Neil Travis), though at times he allows cinematographer Jan De Bont (who went on to direct Speed) to indulge in too many show-offy Big Shots—a vertiginous 360 rotation around the interior of the car is so egregious as to make De Palma’s spinning prom dance in Carrie seem downright static. And whatever inherent misogyny there is in the film’s conceit (that Donna is forced to reclaim her family and save her little boy’s life by literally fighting a rampaging beast to the death) nearly disappears in the face of Dee Wallace’s emotional agony and towering strength as Donna. Too often relegated to ineffectual mom roles (E.T.) or screeching weirdo side characters (The Frighteners), Wallace was given a prime piece of raw meat to chew on here, and it’s a nearly classic performance. The last third of Cujo takes place almost completely inside of a stalled car, baking in the summer sun, and Wallace emotionally navigates the tiny space with aplomb (and she’s helped immensely by Danny Pintauro’s distresing, difficult physical work as terrorized Tad).

With her mix of panic and pity, Wallace gets what makes Cujo such a thoroughly untraditional horror movie: the central monster lacks motivation, it’s just a lumbering, besotted animal, yet its insatiable hunger forms a nearly insurmountable obstacle. When the unforgiving hostility of a diseased nature comes banging at the car door, all that’s left for Donna to do is react with maternal instinct. Stripped down and bloodied, forced into desperate action, Wallace finally makes for one of cinema’s most plausible action heroes. —MK

Third Night:

The Devil Rides Out

Even in The Wicker Man, where Christopher Lee’s Lord Summerisle persists in propagating the rural town’s pagan beliefs against a forfeit crop, the moment of judgment—as Sergeant Howie condemns him for the inevitable day when the islanders offer Summerisle instead as sacrifice—makes Summerisle as sympathetic as Howie. Lee’s was a career of monsters, and like all great monster men, he is an actor profound for asking our empathy at all times. But the flip side is that Lee was, perhaps, more naturally the first-class stalwart the better angels of his evil natures only suggested. He was too infrequently cast as the good guy, when the grand Holmes of Billy Wilder’s lovely Private Life or the regal Duc de Richleau of Terence Fisher’s The Devil Rides Out suggest how really admirable so few protagonists are.

The Hammer films in general, of which The Devil Rides Out is one, have aged terribly; the on-the-fly atmosphere looks cheaper than cheap today, embarrassingly eclipsed by the handheld independents that made horror movies anyone’s game (Night of the Living Dead was released the same year as The Devil Rides Out, 1968). Why watch Terence Fisher’s Dracula when you can watch Browning’s, Murnau’s, Herzog’s, Madden’s, or even Coppola’s instead? For Lee, of course. But after Lee, what then?

But The Devil Rides Out is an exception, on a very modest scale, with a sense of fear almost palpable in a resolutely stripped-down approach to nightmares. Lee plays the Duc, who vows, with a few friends, to recover the out-of-touch son of an old comrade. They find the kid, named Simon, on the verge of immersion into a Satanic cul—the Left Hand Path—led by the commanding, ingratiating Mocata (Charles Gray). The date is nearly May Day, half a year from Halloween, but the feel of fog on country roads and candles in old British manors is nothing if not late October.

The Duc spends days in the libraries of London, speaks of “esoteric doctrines” in his rolling timbre, and summons God’s might (with God’s own voice) in his climactic incantations. He is a blue-blooded sartorialist, like his friends, who promote with their demeanor the temperate pluck of honest, titled British landowners that the far-wandering crazies who populate the equally rich Left Hand Path demean, invert, and offend. The Duc’s friends enjoy brandy—“we can certainly make use of these,” smiles the Duc to his guests of a haunted evening—and their best clue comes about by one of them recognizing a young protégé of Mocata’s from the baccarat tables in Biarritz.

Like Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon or Mark Robson’s The 7th Victim, The Devil Rides Out clothes its Satanists to the nines. But The Devil Rides Out is more properly kin to Night of the Demon, though all three are occupied with the psychology of persuasion over lonely men’s souls. The 7th Victim is as true to human sadness as any movie, but is not, at its heart, supernatural; its Satanic cult summons no demons, no wraiths. The men and women are powerless but for the cheap degradation they realize on still weaker souls than they. In The Devil Rides Out, like Night of the Demon, hell is physically manifest in monsters in place of metaphor. In fact, neither film can accommodate the special effects needed to procure a larger-than-life ghoul of necessary terror. But they try. An “infernal spirit” in The Devil Rides Out recalls nothing so much as the lidless Carrefour from Tourneur’s I Walked With a Zombie, but that is as near as the beasts get to frightening.

Far more successful is the deeply elemental nature of The Devil Rides Out's agenda of dark magic: fear of somnambulists, of bodily possession, of the sudden drop in temperature of a warm room or the inexplicably failing intensity of a candle’s once-bright flame. Eyes are everywhere prominent in dewy, piercing close-ups. Simon tries to choke himself in a bout of demonic epilepsy, Mocata communicates through mirrors and dreams. There are séances, circles drawn on hardwood floors in chalk—where the Duc pours water into a small dish and salts the flame to communicate with the dead—and even a basket of chickens kept in the closet in an observatory at the top floor of an ancient estate.

At one point, Mocata returns to the manor of the Duc’s allies to intimidate them. Mocata is alone; after leaving his card with the butler, he hypnotizes his hostess, and leaves only when the fortuitous intervention of a young girl interrupts his exercise. Deterred but nonplussed, Mocata departs by the front door. The hostess, through a window, watches him leave, and there is something, as Mocata saunters off with his hat on his head and a cane on his wrist, that is simply, fundamentally unnerving in its ordinariness. The Devil Rides Out, but for Lee, is just that—ordinary—and that is where its strangeness steals through.—Nathan Kosub

Fourth Night:

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

Philip Kaufman’s 1978 remake of Don Siegel’s rightfully beloved 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers has always been embraced as a successful reimagining of the classic existential terror of identity theft made sci-fi—yet has it ever gotten its full due? Aside from a memorably hyperbolic review by Pauline Kael upon its release, Kaufman’s film has always seemed to receive a general pat on the back for its efficiency as a scare machine (undeniable) and the cleverness of its conceit, updating the metaphor of aliens propagating mass conformity from the American suburbs to the post-free love urban anxiety of San Francisco (tenuous). Yet what Kaufman most gets right is something more direct: an almost perfect intermingling of the physical and the psychological, a horror film that functions as an emotional, humane allegory on the difficulty of maintaining the self as well as a confrontation with the sickening realities of the flesh.

In a sense, Kaufman, who never made another horror film, gets at the pallor and grit of body horror better than even Cronenberg ever has (with perhaps the exception of The Fly, another remake). Much of the fun of Kaufman’s Invasion comes from the decimation of the new-agey psychobabble uttered by Leonard Nimoy’s celebrity quack doctor, and Jeff Goldblum’s incredulous reactions to it (a precursor to his Jurassic Park skeptic); but most of the unpleasantness (a must in horror) comes from Kaufman’s refusal to shy away from the actual physical transformation—implosions, disintegrations—that must occur for the alien seeds to fully take over our planet. No longer simply a tidy way of getting at the anxieties of the modern age (all the Invasion adaptations, including this year’s woebegone, machine-tooled update, take a stab at social relevancy), this revision makes the interior exterior, the horror coming from within and without. Cronenberg foregrounds his theses too much, especially in this period of filmmaking, basing his films seemingly solely on his own studied theories on the body politic, and the narrative strain always shows. Kaufman’s film, from a superlative script by W.D. Richter (who also wrote, oddly, Jodie Foster’s wonderful Home for the Holidays), is developed with character, plot, motivation…the narrative directess that so often eludes Cronenberg.

Body Snatchers ‘78 works in the same register as John Carpenter’s terrifically scary 1982 The Thing, creating an agonizing, “who can you trust?” situation and then letting the fears explode from within. Carpenter’s film is slightly less fearful of being tagged as a “B-movie,” which makes it even more trustworthy than Kaufman’s film, which aspires to something more self-consciously artful. Yet Kaufman’s technique feels appropriately off in the way it mixes the methodical paranoia thriller of the 70s (Sutherland’s phone-booth montage, in which everyone seems to know his name at every government hotline he calls, feels right out of Pakula) with the yucky creature feature. Two unforgettable moments are only achievable through prosthetics: Matthew surmising a gradually forming double of himself that’s slid out of a pod, before hacking its face to bits with one thwack of a garden hoe (in sickening close-up); and a remarkable shock cut to a pod-person that’s inadvertently been transformed into a dog with a human face, a mutation that’s all the creepier for the casual way in which the other pod people regard it.

Kaufman’s most famous addition to the Body Snatchers legacy was the memorably horrific sound the pod people make when they open their mouths; with Edvard Munch-like gaping maws, they screech an unholy otherworldly sound, meant to identify those who haven’t been transformed yet. This leads to a final scene that’s not only the scariest in the entire series but also perhaps the greatest ending in the history of horror films: the final five minutes of Kaufman’s film are so expertly directed, acted, and calibrated to audience expectations, so smartly adhering to the manner in which we watch movies and the way we allow editing and composition to relate stories to us, that his final trick is like a slap in the face. The effect is devastating, even more so than that hand from the grave in Carrie. And all that’s left is silence; Kaufman zooms into a mouth’s black hole, traps us inside the body, and as the credits roll, doesn’t even give us the comfort of music. —MK

Fifth Night:

Paperhouse

Here’s something strange: a not quite supernatural, almost-horror, killing-free, absolutely terrifying British film from the late 1980s. Still not available on DVD in the U.S., Paperhouse, from Bernard Rose (who went on to make 1992’s unsettling, if ultimately excessive racial alle-gory Candyman), is one of those movies that largely takes place in the literal world of nightmares. This sort of narrative framework usually gives filmmakers carte blanche to go to any lengths necessary to achieve their effects, atmosphere, scares, etc—to abandon logic in the face of dream space and temporality. The results can be predictable, lazy, or unrestrained; outside of David Lynch’s sui generis oeuvre, the dream world is difficult to capture yet easy to exploit. Even the slasher granddaddy of dream films, A Nightmare on Elm Street, quickly degenerated into a random assemblage of creepy pops and jolts; and—with the exception of the ridiculously coherent gay metaphor in Part 2: Freddy’s Revenge—the sequels aren’t even worth writing about.

The film-as-dream, horror-as-nightmare metaphors and attendant psychoanalytic theories are too tidy to bring up here, and too easily deployed to buoy lazy filmmaking; yet Rose’s Paperhouse earns the distinction it so clearly invites. While much of the film plays like a full-moon fever dream, it’s mostly grounded in a specific reality: that of childhood. Anna, a sullen, preteen with divorced parents, haphazardly doodles a rough drawing of a house during a school lesson. Soon enough, Anna is diagnosed with glandular fever, which sends her off into states of delirium and odd fantasies in which she enters the world of the drawing: the crummy pen-on-paper stick house becomes in her alternate dream reality a stark, foreboding house desolated on a grey moor. As she falls further into sickness and her own delusions, she begins to realize that she can adjust her dream world to her whim: therefore she sketches a boy’s face in the upstairs window, peering out a sad, downturned frown. When she sleeps, the boy appears; yet he has his own reality to contend with.

Thus, Paperhouse‘s major difference from other films about dream states is that Anna can, seemingly, control her own subconscious; rather than fearing sleep, she embraces it, at first, as an alternate world she can command. What’s even more magical then, is that the film, aided in no small measure by a wonderfully low budget, never takes Anna away from this single, washed-out setting; it never opens up into an elaborate “world of fantasy,” and its eventual terrors come from surprising, and thoroughly upsetting, directions. For most of its running time, Paperhouse plays like one of those children-retreating-into-fantasy-world films, although what sets it apart is that it doesn’t paint in broad, black-and-white strokes: Anna isn’t escaping abuse or real-world terrors so much as normal preadolescent anxieties and parental distrust, and her unspoken fears and hopes play out in abstracted form where no one can see, or hear, or abort them.

Unlike the more literal Heavenly Creatures or the deplorably simplistic Pan’s Labyrinth, this film doesn’t posit the dreamworld as a viable opposition to “real” fears. Rose is careful to never spell out her neuroses, allowing the dreams to fill in the character’s blanks. The film respects the odd, insoluble dictates of childhood: often it feels more like the great children’s book The Velveteen Rabbit than any film, with its wish fulfillment turned insidious, enacted within the boundaries of a feverish child’s bedroom.

Despite these comparisons, when Paperhouse gets scary, it gets scary: in ways both motivationally sound and horribly inexplicable. Imagine this: a silhouette of a man, off in the distance, perched against a darkening night-time sky, his hand clutching an elongated hammer, bellowing “I’m blind!” To describe who he is, how he got there, or where he’s going would ruin the experience. Once the images, sounds, and moods from Paperhouse get into your head, they’re lodged there permanently—sort of like, it must be said, nightmares from your childhood you never forget. —MK

Sixth Night:

Trouble Every Day

Claire Denis isn’t generally ranked amongst horror’s foremost auteurs, but if she were to be judged solely on the basis of her overlooked (yes) masterpiece from 2001, Trouble Every Day she’d far outshine the competition. Even if I Can’t Sleep flirted with amorphously terrifying serial killer hysteria, and No Fear, No Die’s cockfighting sequences were marked by a filmmaking intensity that her cool elliptical sensibilities generally seemed to belie, Trouble Every Day seems almost to spring from nowhere. Almost. Her previous film, Beau travail, though far from horrific or scary, mounts an impressive desert-bound dread that explodes in the pure catharsis of its final dance sequences. If horror filmmaking need succeed at anything, it’s not in the creative application of plasticine gores or twisted pretzel-logic murder sprees, but in simply, effectively building and releasing tension. And it’s in Beau travail where Denis announces herself master of this simple, yet elusive function.

So what’s scary about Trouble Every Day? Basically, everything. Denis keeps audiences almost completely in the dark about the scientific experiment gone awry that’s mutated the sexuality of leads Vincent Gallo and Beatrice Dalle, and the weight of potentially awful happenings hangs heavy over the film—what is Dalle up to that forces her husband (Alex Descas) to nail her door shut? Why is it that Gallo, in wintry Paris for his honeymoon, cannot consummate with his young bride (Tricia Vessey), in one startling sequence initiating sex only to run into the bathroom in terror to masturbate? At this point in her career, the building blocks of narrative are merely her playthings—she can do what she likes with her captive audience as a result. Unlike real science fiction, Denis isn’t interested in explaining the specifics, which only opens up room for horror to crowd in once the blood starts to flow.

Which it does, and in grand fashion. Prior to the massive bloodletting at its core, the film’s color palette is largely muted—grey skies, coats, rooms. Think of that signature image of Gallo on his hotel balcony: he’s so ashen he almost dissolves into the twin grays of his peacoat and the stone gargoyle he’s standing in front of. Contrast that to Dalle, soaked in blood head to toe from literally devouring an unsuspecting gentleman caller, prancing through the most beautiful sexual carnage on celluloid, idly tracing her hand through blood. It terrifies not only because the Grand Guignol portrait is painted so seductively but also because of the raw sexuality that led to it—who hasn’t wanted the heat of passion that makes one want to consume their partner? Same goes for Gallo’s deadly cunnilingus performed later in the film. What begins as the kind of abrupt sexual courtship between strangers not altogether unheard of in French cinema ends with unholy shrieks and a pool of blood. (Hopefully the orgasm was a good one.)

To be sure, this is horror for the art-house set, but that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily an impenetrable experience for those weaned on the more hyperkinetic multiplex scare. Denis, one of the few filmmakers working who is in full command of the seductive power of great images paired with the right sounds, might just be able to play to the cheap seats.Jonathan Rosenbaum opined about her equally as assured 2004 feature L’Intrus, “Like many other films by the gifted and original Claire Denis, this ambitious and mysterious 2004 French feature is something I admire without especially liking.” I wonder what he thought of Trouble Every Day, but there’s no review on the Reader site to suggest an answer. Saying one “likes” Trouble Every Day may be to align oneself with the forces of darkness, but fuck it—this is Halloween after all. —Jeff Reichert

Seventh Night:

The Others

Alejandro Amenabar’s The Others holds the singular distinction of being the only film I’ve ever seen that caused a fellow audience member to throw a bucket of popcorn into the air in terror. The Others only has two or three big scares—the popcorn-tossing came about halfway through, when Nicole Kidman’s Grace falls to the ground after a door slams into her face—and each of its scream-inducing moments involves an unexpected physical jolt. In a film that’s all about mood, mystery, and the unseen—the ghosts who may or may not be lurking just around the corner or hidden somewhere in the darkness—it’s the abrupt intrusion of physical menace that really terrifies.

Set just after the end of World War II in a musty old house on Jersey Island, The Others is essentially a haunted house tale. Grace (Nicole Kidman) shares her magnificent, eerily empty home with her two photosensitive children (Alakina Mann and James Bentley), as well as three spooky servants (Fionnula Flanagan, Eric Sykes, and Elaine Cassidy), who arrive shortly after their predecessors mysteriously vanish. The children’s photosensitivity is so acute that no sunlight is ever permitted in the house; the servants share secrets and make knowing, obtuse references to their past in the home; strange sounds, unexplained disturbances, and the children’s reports of ghostly apparitions have Grace worried that her home is haunted, even though the suspicion flies in the face of her deeply-felt religious faith. Sets, mise-en-scène, lighting, and editing conspire to create some moody atmospherics, but we never quite know what’s actually going on or whom to believe: Are the children lying to get attention? Are the servants malevolent, or just misunderstood? Is Grace the only sensible person in the narrative or the one person too stubborn to admit the obvious truth that something supernatural is going on?

The Others directly recalls and inverts Jack Clayton’s masterful Deborah Kerr vehicle The Innocents. Like that film, it relies almost entirely on cinematic form—shot composition, sound, and lighting—to evoke fear, and hinges on a remarkably effective, histrionic star turn from its female lead, as well as formidable supporting performances, particularly by the children. A permanently darkened old house, things bumping and clattering in empty rooms, and a woman pushed to the point of insanity: it’s perfectly formulaic and old-fashioned in the best possible way. The big third-act twist, when it comes, serves only to reconfirm the movie’s commitment to narrative coherence: it doesn’t so much upend the story as complete it, making sense of the disparate pieces while giving the film a hefty emotional punch. After the movie’s mystery is resolved, we’re left with a simple tale, well told, an unnerving portrait of a family dealing with loss and shut off from the outside world. You could call it sturdy; you might also call it classical—a horror film as elegant and sad as it is frightening. —Chris Wisniewski

Eighth Night:

Halloween

The era of the horror remake is upon us—they’re cheap, fast, and decidedly not out-of-control, and their cynicism as products is doubled in the amoral construction of their violence. The garbage pile at this point (Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Fog, Black Christmas, Pulse, The Omen) is such a steaming, stinky mess that it’s perfectly understandable that one would greet the prospect of Rob Zombie’s updating of John Carpenter’s 1978 Halloween with, well, horror. Carpenter’s original isn’t simply iconic (a holy grail for slasher generics that many viewers return to over and over, thrilling to its elegant terrors year after year); it’s also a master class in filmic fear, along with, maybe The Innocents, the greatest example of how much anxiety and anticipation can be elicited simply through frame and composition. While Halloween’s necessity as a guidebook for Carol Clover-esque musings on sex and violence is debatable, its craft is unimpeachable and the lore created around it undeniable. Rob Zombie has publicly stated that he will never do another remake, presumably for both artistic and personal reasons (one can only imagine the headaches involved, with the Weinsteins as creative collaborators and the project’s instigators); yet despite his own misgivings, and regardless of the film’s slightly muddled, structural imbalance, Zombie’s Halloween is a force to be reckoned with, and definitive proof that Zombie’s risen above the others in his woebegone generation of gorehounds.

Where Halloween first goes right is in its refusal to try and restage the elements that made Carpenter’s original what it was; by acknowledging the impossibility of re-creating the experience of the first film, Zombie actually pays greater respect to Carpenter than if he had simply done a full-length homage. The 1978 Halloween remains its own discrete work, and the two films do not cancel each other out. Zombie’s fetid, grunge aesthetic is antithetical to Carpenter’s clean, unaffected symmetry, as is the film’s central conceit, which is to psychologize and therefore “humanize” the heretofore seemingly mindless “boogey man” Michael Myers. Carpenter normally forgoes this sort of sentimental editorializing (see also The Fog, The Thing, Prince of Darkness), instead letting evil simply exist among us. This Halloween is undeniably its own entity.

So, the big question, of course, and it’s a valid one, is why? Why doesn’t Rob Zombie just make his own serial killer movie, possibly even jumpstarting a franchise, in which we follow the making of a maniac, from abusive, outcast childhood to his destiny as an unstoppable killing machine? The fact that Zombie, who seems more interested in showing sympathy for his devils than in creating straightforward stalker narratives with clearly defined victims and monsters, projected onto Carpenter’s pre-existing material shows that he fits right in, for better or for worse, with other American filmmakers of his generation, weened on overmarketed imagery, often televised and videotaped, easily accessible and repeatable. To them, the instant iconicity is as important as the craft. Yet like Tarantino, who with the great Kill Bill Vol. 1 and Death Proof has been moving toward ever-more inventive ways of reappropriating pop culture, Zombie is smart about playing with audience’s expectations as well as emotions. Kill Bill seemed the ne plus ultra of epic pop collage (it created its own symphony of colors, sounds, and cinematic intuition); and Death Proof took seemingly familiar “trash” tropes and then stretched and pulled time like taffy, creating an entirely new experience, almost a visual essay, on the very films Tarantino only seemed to be aping. Halloween isn’t quite so heady an experience, but in subtly shifting perception, in making us identify with Michael Myers (a shocking, sickening prospect for the audience), we engage with the film’s mythology in new, invigorating ways.

Of course, the filmmaking itself helps, and Halloween helps further cultivate Zombie’s emerging horror aesthetic, less borrowed from music videos (leave that to the Tarsems and the Nispels) than from heavy-metal music itself: self-consciously “alternative,” punkish, prankish, fixated on its own outsider status, reliant on transformative costumes and punishing grotesquerie. As evidenced by House of 1,000 Corpses (just feeling out the territory, but undeniably scary) and The Devil’s Rejects (an obvious heart-on-its-sleeve auteur piece), Zombie likes getting his audiences trapped in claustrophobic, mentally deranged funhouses. This is why his Halloween has a stronger initial half: he extends Carpenter’s best, most horrific bits (one five-minute-or-so take, originally) into an entire first act. It’s uncharted territory, and it’s extremely upsetting to wait for the heavy-lidded, blonde-haired prepubescent Michael to finally exact revenge on his abusive father, teasing sister, and school bullies. The way Zombie stages these scenes may be crass (his parents, William Forsythe and, of course, Sheri Moon Zombie, scream and spittle and swear like actors in some hellish dinner theater production), but as it builds to gruesome violence it attains a certain dignified grandeur. By comparison, Michael’s Halloween night rampage decades later goes through the motions a bit too much; Zombie’s not as interested in staging stalker scenes as he is at thrusting us into depraved mindsets.

Yet if he doesn’t want to startle with cheap jumps or buzz his viewers’ seats, Zombie does scare us with the physical exertion of killing. Nobody in American horror today is as good at the labor and viscera of murder, and what the late scenes of Michael endlessly going after the babysitters and his sister Laurie (and yes, the no-nonsense Jamie Lee Curtis is sorely missed) lack in calibrated tension they more than make up for in frightening size and speed. When Halloween was over I felt fittingly terrorized, and not in any sort of hollow way; Zombie’s version is audacious (emotionally) in its simultaneous repackaging and refuting of Michael Myers as a symbol of evil. He may forgo the hallowed notion of ambiguity in horror (too many believe that grants instant artistic integrity), but in peeking behind the mask Zombie does manage to complicate and cultivate our relationship with a figure who’s been, for almost thirty years, a fixture. And as resolute as a gargoyle. —MK