Tight Little Island

Michael Koresky on Three Times

The Hou Hsiao-hsien project—of fragmented history and abstracted memory, of floating cameras and infinite takes, of obscured motivations and unseen consequences—has the support of the entire cinema intelligentsia behind it, yet for all its visual and social richness, purposely makes its viewers into observers rather than participants. For all of Flowers of Shanghai’s suffocating ornate warmth, never have I felt anything other than left out in the cold, watching as its characters move through inexorably doomed trajectories with a helpless detachment. And though The Puppetmaster’s burnished, self-effacing, and ambitiously small detailing of the Japanese occupation of Taiwan in the first half of the 20th century is enthrallingly conceptualized—narration itself rather than dramatization becomes the main thrust, putting onscreen the tangential details other biopics would leave out while compartmentalizing the grand historical plot points into direct-address documentary-like interjections—the resulting viewing experience registers as purely intellectual rather than emotional.

There certainly is something to be said about the difference between “getting” a Hou Hsiao-hsien film and getting a Hou Hsiao-hsien film, yet his newest film, Three Times, throws all of my concerns into a void. Perhaps it’s the short-film form (for Three Times consists of three separate tales, each informed by the others in both appealingly superficial and intractably theoretical ways) that has unveiled for me Hou’s emotional center. Yet I’m more quick to assume that it’s just this particular film, and what it says about personal versus political histories, the ever-shifting placement of women within society, and sexual communication, that has somehow coalesced so much of Hou’s visionary strands. Overused words like rapturous and hypnotic certainly apply to Hou’s technique here, even as the film jumps between eras and political realities, yet there’s something so much greater and more challenging going on in Three Times than aesthetic control: by staying in a constant implicit dialogue with one another, both in narrative and historical modes, of politics as well as of cinema, all three stories become the tale of Taiwan, a palimpsest on which universal themes stand in for the reality of a single island as it’s passed from one imperialist ruler to the next—the history of his country written as a triad of minimalist romances.

Three Times begins in 1966, lushly, with an elegant, awe-inspiring little glide down from a vaporous hanging lamp to a pool table as a group of attractive rural youths clutching cue sticks encircle the lightly rolling colored balls; one after another has his or her turn, while Hou’s camera, as drifting yet concise as ever, moves effortlessly from game table to the distracted glances of the players. Most striking in this crowd is luscious, full-lipped, and impossibly gorgeous Shu Qi, Taiwanese pin-up and central figure in all three of Hou’s tales. It’s Shu Qi’s visage (and how it reacts to differing forms of social and sexual containment) on which Hou will hang all three tales as they unfold back to back. Yet here in this opener, “A Time for Love,” her glamorous and indifferent introduction is as deceptive as that hazy, Wong Kar-wai-sh gauzy filter that’s laid over every shot. Earnest local boy Chang Chen falls for her before being shipped off for military service; upon his return he finds his beloved no longer an employee of the pool hall he had frequented and in her place another girl of similar age and beauty. In trying to track her down, he dashes from town to town, only to find in each village in which she had been rumored to have taken up work that she is replaced by another pretty young woman. Their eventual reunion and subsequent simple expression of mutual burgeoning love (a lovely hand-hold in the rain before he must be shipped off to the base at 9 a.m.), ends the first “Time” on a reconciliatory note that the following two “Times” will not only circumvent but also conceptually deny. And in retrospect from the political and social tangles of the other stories, the overly aestheticized innocence of “A Time for Love” gives off a whiff of odd conventionality. Permeated by the constant replaying of romantic pop tunes (The Platters’ “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” Aphrodite’s Child’s “Rain and Tears”), the languor seems ultimately insufficient in the face of such complex national history.

Shu Qi’s exquisite work in the second chapter, “A Time for Freedom,” lays bare the shortsighted romanticization of what came before it. This masterfully modulated work of art, set in 1911 and told as a silent film, complete with delicately ornate intertitle cards (which at first register as charming gimmickry yet soon become completely conceptually inextricable from the narrative) and a heartbreakingly quiet piano accompaniment, might take its style and setting cues from Flowers of Shanghai, but it has a visual and emotional power all its own. Here, Shu Qi’s courtesan is frequently visited by Chang Chen’s radical newspaper man, a revolutionary who fights for Taiwanese release from imperialist Japanese rule when not in her arms. As usual, Hou’s camera moves delicately from character to character, from Shu Qi to Chang Chen and back again, picking up on the slightest expression of underlying passion, whether it be politically or romantically anchored. So overwhelmingly quiet and meticulously designed is this scenario, and so unassumingly does its narrative power creep up on you, that Hou’s firm grasp on the blind spots of political engagement might not make itself immediately apparent. Yet Shu Qi’s courtesan remains in her own emotional and social bondage while her seemingly devoted lover speaks of Taiwanese freedom; in the actress’s face we see years of emotional enslavement, compounded by the tragic yet matter-of-factly presented subplot of a 10-year-old girl being primed for the life of a courtesan and possible concubine. Hou’s point, told gently and refracted through the sigh of a love story, that grandiose political gestures often occur at the expense of the individuals still toiling away in their workaday social realities, comes across effortlessly—and puts to shame the finger-wagging grandstanding of the more self-consciously political Manderlay, in which Lars von Trier similarly proposes that international relations cannot be resolved until a country first corrects its own domestic policies. Yet where Trier dredges up the past to angrily, misguidedly accuse the present of lack of foresight, Hou Hsaio-hsien, with a hush, details the ongoing tragic ironies of history (Shu Qi’s gentle uncovering of her lover’s devastating hypocrisies—that he believes in freedom yet ultimately helps pay for a concubine’s enslavement—is heartbreaking), then simply moves forward to the present, with a dramatic cut from the courtesan’s candlelit den to a speeding motorcycle scrambling across a clogged cityscape.

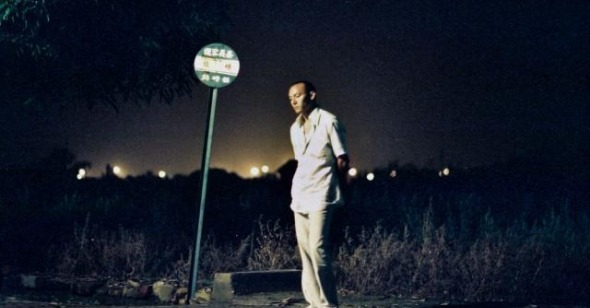

With “A Time for Youth,” Hou simultaneously coalesces and breaks apart the entire endeavor, both bringing the entirety of Three Times into tight focus and revealing the inherent dangers in defining an era solely through the representation of a man and a woman. This third chapter, bathed in dusky evening glow and neon blues and greens, has been most often compared to Hou’s 2001 Millennium Mambo, both favorably and not, yet like “A Time for Freedom,” the 2005-set “Youth” needs to be considered on its own terms, away from Mambo’s more ethereal trappings—for all of its meandering and nightclub posturing, Hou’s closing segment is Three Times’ most concrete and troubling. Finally, the gorgeous images of the sultry Shu Qi and the sexy Chang Chen betray us as viewers; we are persuaded by the two other shorts, and implicitly a century’s worth of iconic male-female coupling, to follow their latest incarnation, this time as a young duo explicitly sexually involved with one another, as the central love story. Yet Hou seems to be begging us to look at this so-called love story with a sidelong glance; as the full consequences of this tale, full of the requisite modern-day spiritual malaise and technological overload, become clear, we realize that indeed there has been a love story here, yet it has emerged from the peripheries, by way of an unexpected third party. And Shu Qi’s (and our) ignorance of it has tragic consequences. A surprise from Hou: the hetero norm, seen in different shades of illumination in 1966 and 1911, has finally been busted wide open. Yet despite this, Shu Qi and Chang Chen ride off together on his motorcycle, ignoring their possible incompatibility in favor of the safety of each other’s grasp, typified by the epileptic Shu Qi character’s clinging to her boyfriend’s body for dear life as they careen down the highway.

Hou’s questioning of the validity of this final couple, caught up in the everyday communication tangle of text messaging and email, and the artistic shortcuts of bar karaoke and computer music-writing programs like GarageBand, throws the entirety of Three Times into dazzling, retrospective illumination: How does the idea of the normatized couple, reflected idealistically only in the 1966 segment, function when so completely wedded to the environmental and political truths of which it is a product? Well, in love, history, and the stranglehold of social codes, there is no one easy answer. In this expansive and personal vision of Taiwan, history isn’t a straight line; rather it’s a constant dialogue, a search for a mutual understanding between both people and eras, from large-scale occupation to individual self-delusion. It all sounds grandiose, yet Hou never makes grander claims than his delicate balancing act can sustain; it’s embedded in the text, in history, and for once, Hou made me not just understand it but feel it.