Better Left Unsaid

Nathan Kosub on Three Times

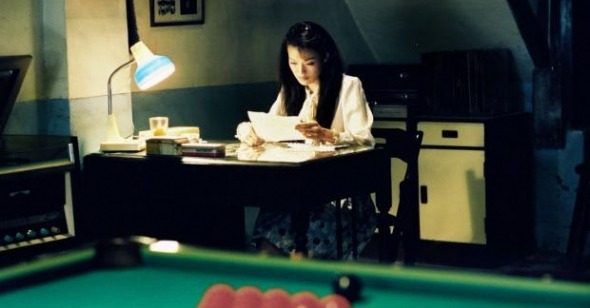

In “A Time for Love,” the first section of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Three Times, Chang Chen plays Chen, a soldier who falls for girls he meets in poolrooms on nights when he’s on leave from the army. The film, comprised of three parts, is for all intents and purposes about love. Chen asks if he can write the women letters, then sends short missives with sentiments like “stay beautiful.” Because the jobs the women hold are transitory, the women are often gone when Chen returns. One night Chen decides to track down one of the hostesses, May (Shu Qi), and he eventually finds her in Huwei, where they reunite over a late meal. The story is saccharine but harmless. But why not expect more? Whatever familiarity the train ride from Kaohsiung to Huwei might have for Hou’s hometown crowd, there is no sense of space in the signs that mark each township Chen crosses in search of May. Is Chen traveling hundreds of miles? Tens? Those signposts suggest so much we could be seeing, instead of the meticulously appointed (and thus, false) poolrooms we’re shown.

What Hou loses in the confusion of space and time is the potential to say something about local sojourns. In a big enough city, you can move from one nightspot to the next, from neighborhood to neighborhood, and it can seem to others that you have left one life—one place—behind and moved on to another, when in fact you may be simply taking a different bus on your way home from the bar. A country so geographically divergent across so relatively short a distance as Taiwan is the heart of the rural/urban relationship in Hou’s earlier Goodbye South, Goodbye, and Hou wastes an opportunity to expand on that here.

But it’s more appropriate to judge “A Time for Love” for what it is instead of what it isn’t. The mid-century setting, the pop songs, the rain that falls as steam rises at a noodle stand in Huwei: we’ve seen this before, but it’s possible to talk about the segment’s failures without comparing them to Wong Kar-wai. Fashion magazines love to document new couture lines by sending models in impossible dresses to construction sites full of machinery and beefy men; when May stands beside the cabin on a tugboat ferry across Kaohsiung Harbor, the fading light graying everything except the cream silk of her tailored blouse, we no longer pay attention to her face, but remain fixated on her clothes. She is emotionless: an advertisement. Likewise, Chen’s perfectly fitted pants in no way suggest the shy soldier, who would be too timid for such style. If Hou is selling sweetness and light, why are the lovers as unapproachable as dolls?

Additionally, pool is a terrible device for movie courtship. Never mind that Hou’s technique in filming the table looks like a butchered pan-and-scan transfer; as a hobby, pool doesn’t suffer amateurs gladly. Unlike shuffleboard or darts, which have more manageable learning curves, practically nobody can play billiards well. Consequently, tableside flirting is reduced to self-conscious laughter (or else tiresome, reflexive bravado) about badly executed shots. Superficiality rules the day, as it does with so much of “A Time for Love.”

The best scene in “A Time for Love” is the couple’s reunion in Huwei, when Chen finally catches up to May, and they court with smiles and say nothing. Eventually she offers him tea, asks him to take a seat, and retrieves a cigarette for Chen from one of her friends. His expectation that she do all of this for him is how the period setting of “A Time for Love” finally, first, becomes relevant, and, second, makes sense. Otherwise, so much of the section is so broadly sentimental—the tenuous but eager joining of hands at a bus stop, say—that real emotion is reduced to social gestures that rely on our own experiences to impart a sense of romance. And that’s no romance at all.

Indeed, if it weren’t for part two, “A Time for Freedom,” Three Times might have been the one that got away. In “A Time for Freedom,”’s 1911 Dadaocheng, an intellectual named Chang (played by Chang) intercedes on behalf of a concubine made pregnant by a member of the Su royal family, and in doing so compels his own concubine (named Mei, played by Shu) to ask if Chang would consider buying out her contract. She is convinced there’s a bond between them, but he, so full of opinions and poetry with regards to Taiwan’s fate, has only silence for her. Eloquent about the country, he shows nothing for the woman who loves him.

The entire episode transpires in silence, with title cards between the scenes and a soundtrack that Hou occasionally incorporates into the action. Mei is a singer; sometimes she performs in sync with the music, other times it is in the background for us but not for her. The device suits the private, unspoken sorrows of the heroine: unspoken because she cannot speak, private because she cannot share them. She is, to my mind, the only hero of Three Times, bravely persevering through a lifetime of others’ disregard for her happiness.

Broadly, Hou’s critique is social. Chang’s unwillingness to help Mei is a product of the system that allows him to lament the handover of Taiwan to Japan but still hobnob with princes. But like the rest of Three Times, that point is secondary to the love story, which is personal. Words and actions are different things. The right political favors excuse strong-willed editorials, but Mei is permitted neither a voice nor escape, and her fate is not particular to lovers in the early twenty-first century.

Thus part three, “A Time for Youth,” is set in 2005, the year Hou directed Three Times. This time, Hou’s protagonists are a photographer and a singer, two limelight junkies of material aspirations. Jing (the chanteuse, again played by Shu) is an epileptic. She and Zhen (Chang) have an affair though both are in relationships with other women. They communicate by cell phones and computers when they are not at his apartment making love or on a motorcycle on the freeway.

“A Time for Youth” is immersed in the physical: sex and the city. Jonathan Rosenbaum famously declared that Jacques Tati’s Playtime—a movie made up entirely of sets—taught him how to live in Chicago, but I appreciate the ways that Hou’s characters move through the very real landscape of Taipei: how Zhen parks his motorcycle on the sidewalk; how Taipei’s right-hand traffic lanes are the exclusive province of men and women on two wheels; how vendors shoehorn themselves in the thin medians between people and roads. The action tries to ape the city’s speed in encounters that are sloppy and emotional, but if Hou wants to document the breakdown of communication in the 21st century, or the inescapable loneliness of city-dwellers, his message is clipped by too much shorthand for run-of-the-mill repression. What is Jing’s epilepsy except a metaphor for inarticulateness and public embarrassment, the two taboos of late-night cool? Her tattooed throat is no more profound than the lyrics she sings in English; unencumbered by a bad translation, their silliness jumps off the screen: “Celebrate when you’re honest to yourself?” Not that honest!

I scorn such devices as a jilted lover’s threat of suicide—that is, I condescend—because Hou does nothing to convince me not to. I don’t believe that Jing’s angry girlfriend will kill herself any more than I believe that Zhen likes any of the women in his life more than the self-portraits he takes. If Hou argues for the truthfulness in a mundane cell phone declaration of love—if he argues that good writing is not needed to embellish what the heart wants to say—then why is “A Time for Youth” fiction? Nightclubs, noisy restrooms, point-and-shoot digital cameras: even as the mise-en-scène telegraphs immediacy to the characters’ actions, the actions themselves founder for want of the structure that gives stories meaning. Is someone my age supposed to recognize Jing or Zhen’s behavior, and thus fill in the blanks? Is the title “A Time for Youth” meant to simplify Hou’s message or excuse its shallowness?

Communication is the subtext of Three Times, but every commitment between people that cannot be conveyed except in person underscores the failure of every effort in love except action. If Hou cannot depend on his characters’ actions to speak for him, then he, too, fails. Because dialogue is excised from its soundtrack, “A Time for Freedom” is the cleanest separation in Three Times between heart and mind. If there are never excuses where the heart is concerned, there is nothing that needs to be said.

In all three stories, the written word—in longhand, by text message, by e-mail—is insufficient to convey the author’s intentions. Chen the soldier sends letters to hostesses in poolrooms without knowing whether or not the women read his barracks-bound complaints; the happiness Chen finds sharing a meal with May is genuine in a way his wistful recitation of song lyrics never is. Chang’s letters to Mei are personal only insofar as he took the time to transcribe his thoughts to paper and post them to her; in content, the letters read more like a private exercise in improving upon the public articulation of a topical political position. Electronic correspondences in “A Time for Youth” are sent late at night and read by distracted eyes; the messages are emotionally revealing in an unexamined way, but offer little solace to the recipients who read them en route to other activities.

“A Time for Youth” only seems more daring insofar as a tracking shot along a freeway feels less old-fashioned than the structural formalism of a silent film. Cell phones and e-mails typically still belong to franchise horror movies, so it is nice to see them used thoughtfully. But the successes and failures within Three Times are wildly divergent. Only once do Chang Chen and Shu Qi seem like actors instead of models. Only once does the period suit the script (and in a movie like this, 2005 is a period). At two hours and fifteen minutes, one out of three is a lot to ask, but Mei’s pain in “A Time for Freedom” is almost enough to excuse the rest. At least it’s enough to let you know what everyone involved with the movie is capable of—but don’t we have Hou’s other films for that already?