Paradises Lost

Max Carpenter on of the North and Tabu

The titles of both Dominic Gagnon’s found-footage documentary of the North and Miguel Gomes’s Tabu are taken from legendary works: Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North and F. W. Murnau’s collaboration with Flaherty, Tabu: A Story of the South Seas—cornerstones of documentary and docufiction, respectively. While many directors have made references to earlier films’ titles (e.g., Godard’s Rossellini allusion Germany Year 90 Nine Zero), Gagnon’s and Gomes’s titles are more specifically elisions aimed at reframing the original films: “Tabu” is no longer confined to the South Seas; “of the North” is generalized to the whole Canadian Inuit population as opposed to the fictionalized figure of Nanook. Both Gagnon and Gomes seek to expand upon and revise Flaherty’s and Murnau’s classics with their own wholly distinct efforts. Gagnon’s assemblage of online, (mostly) Inuit-shot home videos is a rebuke to Nanook of the North, with a civil libertarian’s emphasis on giving quelled voices a platform. Gomes’s Tabu juxtaposes modern melancholic life in Lisbon with a seductive picture of Portuguese colonialism as an elegy for the ignorance inherent in Murnau’s and Flaherty’s film. Through documentary, Gagnon attempts to right the wrongs of Flaherty’s falsifications by contrasting Nanook the happy Eskimo with a survey of real Inuit experiences, and through dreamy fiction Gomes responds to Flaherty and Murnau’s imperialist ethnography by altering its structure, likening the innocence of South Seas natives in the original film to the innocence of Portuguese colonialists.

Gagnon assembled of the North from a hodgepodge of both unsettling and relatively tame Internet videos. A seasoned editor of provocative online content, Gagnon sifted through hundreds of hours of Inuk-shot footage of life in the Canadian North, cherry-picked arresting and atmospheric moments and stitched them into a tapestry. Unlike his previous online collages—RIP in Pieces America, Pieces and Love All to Hell, Big Kiss Goodnight, and Hoax_canular—of the North is in conversation with cinematic history. It functions as a populist response to Flaherty’s film: this is their North, not Nanook’s. It is now well known that while making Nanook Flaherty encouraged the performance of outdated Inuit rituals and slept with local women—the type of colonialist behavior that invited Gagnon’s power-shifting response. The sketchy reasoning behind Nanook of the North being considered a foundational work of documentary is reminiscent of why the downright fantastical Histories of Herodotus is still categorized as such: both authors confidently purport to have a command over reality and truth.

Gagnon’s film splices goofy home videos, disturbing artifacts of racism, and day-to-day moments in Arctic townships, edited with a knack for finding cinematic snippets within otherwise mundane clips. A massive oil refinery machine inches across the ice, a man comments quietly on an approaching polar bear while seated in a car with his family, another family films itself in front of the television with a GoPro on a stick, and a callous white man cuddles a naked Inuk woman while objectifying her as an “honest-to-goodness-gracious Eskimo.” Adding to the disturbing nature of this latter clip are animal cruelty videos of all shades: seal clubbing, beluga harpooning, goose sniping, whale skinning, the aftermath of a housecat murder, and decomposing dogs. The more quotidian material buffers these horrendous videos and provides points of decompression for the viewer.

In responding to Murnau and Flaherty, Miguel Gomes takes the opposite approach to Gagnon’s, piling on layers of artifice instead of peeling them away. Tabu follows Gomes’s first two formally inventive features, The Face You Deserve and Our Beloved Month of August, in which realistic depictions of modern Portuguese life are overlaid with fairy tale narratives. Tabu’s two-part structure contrasts a drab take on politically conscious Lisbon life with a steamy portrait of Portuguese Africa in the sixties. While the film can primarily be read as a grand metaphor about post-imperial saudade (today we are more humane but also more melancholic than the blissfully ignorant colonialists of yesteryear), it also functions as a response to a film in which Murnau and Flaherty utilized Polynesian natives as actors in a simplistic paradise lost tale, a film that represents an unabashedly colonialist approach to fictionalized documentary.

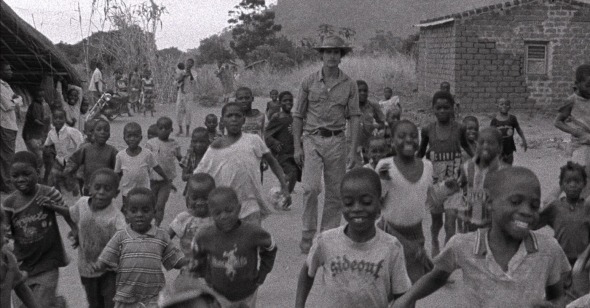

The 1931 Tabu consists of two parts: "Paradise," in which life on the island of Bora Bora is naïvely romanticized, and "Paradise Lost," in which a youthful native woman deemed off-limits to mortals by an island chief is wrested from her lover who relentlessly pursues her until he drowns at sea from exhaustion. Gomes’s film reverses these chapter headings. The beginning in present day Lisbon is "Paradise Lost," and (what appears to be) colonial Mozambique is "Paradise." This reversal is a revisionist jab at Flaherty and Murnau, likening the naïveté of colonialists to that of natives, in turn hinting that the original ignorance was Flaherty and Murnau’s. The African natives in both parts of Tabu are subservient to the Portuguese, either as domestic servants in Lisbon or as subjugated Mozambicans. Their plight is unchanged by the colonialists’ fall from innocence. Flaherty and Murnau’s native subjects were never primitive and never gained any power from their brush with Westerners.

Beyond the dig at Flaherty and Murnau, inverting the “Paradise–Paradise Lost” trajectory is the same swap Saint Paul used in his Roman Epistle to situate Christ’s suffering as the reversal of Adam’s fall. (That is, Adam's sin banished humanity from Paradise and Jesus's resurrection healed the separation.) Intentionally or not, Gomes effectively positions Flaherty and Murnau as cinema's Old Testament and himself as its Gospel. He has noted his great respect for Murnau in interviews, even symbolically equating him with “cinema” in a Reverse Shot interview. Gomes’s Tabu makes use of the academy aspect ratio, and the grainy, high-contrast black-and-white wilderness environment of the original film; it is swelling with love for Murnau and Flaherty’s expressionism. Reverence of the original film as both great cinema and the product of great minds prevents Gomes from completely denouncing Tabu: A Story of the South Seas as colonialist claptrap. Likewise, in Gomes’s film the problematic positioning of the Portuguese Empire as Paradise, albeit a troubled one, persists. As with of the North, a connection to Flaherty sparks a dialectic rather than a solution to Flaherty’s troublesome politics.

Gagnon’s film has ignited controversy over the question of whether it has challenged racist misconceptions or simply promulgated them. Much of the offense at Gagnon's armchair ethnography tends toward the argument that he is an ignorant white Québécois who has never been to the North, that instead of fully expunging white imperialism Gagnon has merely reproduced it in the editing room. A more direct rebuke to Nanook of the North would have been a wholly Inuit-made film, something akin to a documentary version of Zacharias Kunuk’s Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner. By dint of his implicit effort to portray the North more truthfully than Flaherty, Gagnon is also asserting a confidence in his found footage method that introduces similar complications to Flaherty’s approach. Some opponents have more incisively singled out disconcerting material in of the North, reading racism into editing choices—like the juxtaposition of an Inuk’s gaping vagina with a dog’s butt—and taking issue with the mere presence of insulting portrayals of Inuit life—alcoholism, seal clubbing. None of these reactions should be dismissed, and Gagnon himself has acknowledged such concerns. Many original owners of the videos have objected to their use, so for each successive of the North showing he has replaced these with a black screen.

It seems Gagnon’s intention in responding to Flaherty was not merely to create a North-centric Life in a Day—a 2011 doc in which people knowingly submitted self-shot material to YouTube—but to force the viewer to grapple with pre-existing material that corroborates harmful Inuit stereotypes. His ostensible intentions backfired. Critics of of the North are doing their damnedest to make sure that most people will not be able to see the film, and for a time it seemed that they had won their battle: in March, Gagnon’s previous distributor publicly apologized to CBC News for the film and proposed a fully censored version that amounted to 74 minutes of a black screen and silence. Gagnon, however, has since sought successful legal protection for the film’s content and switched distributors. The unedited version of the film is once again on the international festival circuit, and a free streaming version is available online.

Both Tabu and of the North hold confidently contradictory viewpoints regarding issues of imperialist racism. Both respond to Flaherty by reversing the backward aspects of his films, but are left with products that are themselves slightly backward—of the North in its vindication of stereotypes, Tabu in its nostalgia for Portuguese Africa. Tabu’s reception has been far warmer than of the North’s, but Gagnon is used to this. His back catalog features many collages of contradictory, often hateful, conspiracy theorists with little to no signaling of where the viewer’s sympathies should lie. His films often amount to political statements addressing the contentious aspects of free speech. Without voiceovers or narrative sugarcoating, Gagnon’s films are designed to be harder to stomach than any of Gomes’s. Tabu’s agreeableness benefits from Gomes’s choice of narrative fiction: metaphors about colonialism become safer when couched in references to outdated films like Hatari! (from whence it gets its mountain setting and its animal adventures) and Out of Africa (the source of the film’s Europeans-in-Africa love story), whereas Gagnon offers no buffer from the barrage of experiences in of the North.

Gomes orchestrated his brush with controversy quite gracefully, and Tabu was awarded the Berlin Film Festival’s Alfred Bauer Prize for its “new perspectives on cinematic art.” Gagnon, conversely, looks more like a cunning imperialist caught red-handed by Inuit rights communities peddling his assemblage for truth. However, voices within Québécois cinema, including Alfred Bauer laureate Denis Côté, have spoken out in a letter of support for Gagnon’s right to uncensored expression. And it is important to distinguish that of the North’s denunciations have largely been political and Tabu’s accolades have come from arts communities. Receptions aside, Gagnon and Gomes both staunchly address sociological realities and engage with the question of how one can use cinema to inch closer to the truth of social inequalities. If cinema is still a “battleground [of power struggles],” according to Jonathan Rosenbaum in his Chicago Reader article “Life Intimidates Art,” then Gagnon and Gomes are equally dutiful foot soldiers in the army.