Writer’s Block

Brendon Bouzard on Finding Forrester

Apparently, the executives at Columbia Pictures liked Good Will Hunting so much that it commissioned its own version. What they got was Finding Forrester, a singular work in Gus Van Sant’s oeuvre. Singular because of all the career paths and roads not taken in Van Sant’s uniquely personal, constantly evolving approach to the medium, nothing else even comes close to this in serving up sheer horseshit.

I won’t apologize for Finding Forrester, and given how reticent my fellow Reverse Shot writers were to address it, it doesn’t seem like many of them are willing to either. But as much as I’m reiterating how bad this movie is—and yes, it is bad—it simply cannot be ignored. In his piece on Mission: Impossible for Reverse Shot’s Brian De Palma symposium, Jeff Reichert pondered whether or not the oddball misfires and cash-ins of a director’s career are as much their own as the heralded works—thus could Finding Forrester be as important to understanding Van Sant as Mala Noche, and if so, what distinguishes it as a Van Sant work? Exploring the strangely film schoolish Finding Forrester is like undertaking a work of cinematic anthropology—there’s a tougher, more interesting film that the auteurist in me has to believe got ripped away, Welles-style. Briefly compelling moments flash by throughout, only to be drawn back into the murky abyss of inauthentic New York social dynamics and unending basketball scenes. Surely the man who generously gave us Drugstore Cowboy and Elephant didn’t also foist “You’re the man now, Dawg” on the world. How did Van Sant, rearing up for a second renaissance that would start with Gerry and continue through his recent slate of archly formalistic work, make Finding Forrester, and why? Finding Forrester is a film that provokes these sorts of questions and provides no easy answers. If it is truly a Gus Van Sant work, it does a very good job of hiding it.

That Van Sant had directed Good Will Hunting has always seemed like an afterthought to its commercial and artistic success. His direction in that film was workmanlike, unobtrusive, a blankly classical canvas of mid-key lighting and warmly decorated interiors upon which the film’s genially earnest local-color humanism and actorly dialogues could roam unencumbered: a symphony of shot/reverse-shots. And it was, after all, as much the story of its two young writers, endlessly replayed in one puff piece after another, as it was the story of a genius struggling to realize that, indeed, it was not his fault. Though the film displayed some of Van Sant’s most superficially obvious interests as a filmmaker—young masculinity, fringe living—it was as much or more a Matt Damon film or a Ben Affleck film or a Harvey Weinstein film as it was Van Sant’s.

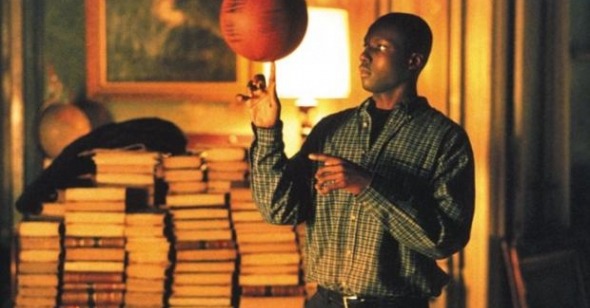

It’s perhaps a strange choice then that Columbia hired Van Sant to bless its own Good Will Hunting prospect with the same breed of unexceptional direction. Stranger yet is that he agreed. Seizing upon a script written on spec by Mike Rich (who has subsequently written The Nativity Story and the heinous Cuba Gooding Jr. vehicle Radio), the studio fast-tracked Finding Forrester as prime 2000 Oscar bait. It gave Van Sant what I hope was a great sum of money for the film, which actively invited comparisons to its predecessor. Jamal (Rob Brown), young, gifted, and black, is a star basketball player with a talent for writing and a mentorship-cum-begrudging-friendship with reclusive author William Forrester (Sean Connery). Recruited from his Bronx neighborhood by a hoity-toity prep academy, he finds himself at odds with the school’s racist English teacher (F. Murray Abraham) and must call upon his white father figure to shepherd him in a time of strife. These sorts of boldly enunciated racial dynamics complicate the film— where Hunting was all gruff Bostonian class consciousness, Finding Forrester’s migration to New York and emphasis on race as a dynamic of Jamal’s struggles overburdens the film’s diffident NPR liberal touch. One can feel Van Sant’s hand being moved throughout. The romance between Jamal and a student played by Anna Paquin is so insipid, so afraid of depicting a genuine interracial relationship that it never consummates into so much as a kiss (Save the Last Dance, released just three weeks later, would seem awesomely progressive by comparison). The hideously overstated—and narratively inert—rivalry between Jamal and a light-skinned black teammate at his prep school, which boils into absurdly literal racial dialectics (“You think we’re the same, but we’re not”), is a studiously facile chunk of Haggis barely worth acknowledging.

Here, as in Hunting, one can see traces of Van Sant’s thematic interests bringing themselves to bear. There’s a certain demythologizing quality to the film—like Elephant or Last Days (or Psycho), there’s an intention here to shed harsh light on a Myth of Modern Society. What Columbine, Kurt Cobain, and Hitchcock’s original film were to those works, here the reclusive Salinger/Pynchon-style literary figure is up for dissection. William Forrester, whose work we see and hear very little of in the film, and what little we do see and hear seems like cut-rate Fitzgerald, is drawn in sharp parallels to Salinger—not simply the reclusiveness but also the misanthropic bite to his reclusiveness. Petty and guilt-ridden, Forrester is the type to block the publishing of a critic’s work on his novel out of spite. He barks viciously and sabotages his enemies. Dig a little deeper and the film’s exploration of the artist mythos begin to resemble autocritique. Jamal, marginalized by mainstream society, adapts to Forrester’s style, even plagiarizing his mentor for a writing contest, and finds tremendous success. It would be fruitless perhaps to draw a direct parallel between Van Sant and Jamal, but the director’s attraction to the project might lie somewhere in Jamal’s third-act moral ambiguity—he refuses to take the blame for copying Forrester’s work as the basis of his own and is eventually vindicated by Forrester himself.

But the film is not all hackery. Among the best scenes are well-observed, semi-improvisational dialogues among Jamal and his friends. They fulfull an obvious expository purpose, but there’s a clear divide between the recognizably human rhythms of these dialogues and the inane platitudes that pervade the film. Though this anthropological treatment reads slightly patronizing—look how authentically black this young man’s experience is!—it’s these scenes, with their unmannered long takes and goofy-casual resonance, that seem most in sync with Van Sant as a filmmaker and certainly most in tune with his more recent aesthetic tendencies. Some of the performances are strikingly good—though Connery hams his way through every scene and F. Murray Abraham is one mustache-twirl away from pure caricature, bit players are given a lot to do: Busta Rhymes, as Jamal’s older brother, a burnt-out onetime basketball prospect, strikes a disarming pathos. Fly Williams III, as one of Jamal’s friends, is a charming braggadocio, probably a more compelling figure than the boringly perfect one at the film’s center.

The film marked the first collaboration between Van Sant and cinematographer Harris Savides, whose elegant, natural lighting is a key to his later films’ acclaim. What unites Finding Forrester’s strengths, however, is that they all play at the film’s margins. Only at the moments which matter least does any sense of authorship come into play—the aforementioned improvisations, the fourth-wall breaking opening credit sequence, which begins with a shot of the film’s clapboard and continues with faked documentary-style vignettes of Life in the Bronx (again, a patronizingly anthropological tack) set to slam poetry. Under normal circumstances, I’d dismiss this sort of thing as wankery, but here, it’s the highlight, the one moment where you feel an unencumbered authorial touch. Self-indulgent as it may be, it doesn’t deserve the ennui that follows. Finding Forrester doesn’t indulge Van Sant’s talents—it smothers them.