The Lonely Guys

Greg Cwik on The Long Goodbye and Mikey and Nicky

The Long Goodbye screens February 10 and 11 and Mikey and Nicky screens February 12 and 18 at Museum of the Moving Image as part of the series Snubbed.

The loneliest moment in someone’s life is when they are watching their whole world fall apart, and all they can do is stare blankly. —F. Scott Fitzgerald

I’m sure that most reading this would agree that American entertainment awards, particularly the Oscars, are not really given out based on merit. Lavish opportunities for Hollywood’s elite to flaunt their conventional ideas and pat themselves on the back for it, the Academy Awards have often overlooked cinematic works that stand the test of time, as Museum of the Moving Image’s new screening series Snubbed, featuring a wide swath of movies that received zero nominations, attests.

Films that have traditionally been rewarded by the Academy follow discernible arcs, provide closure, and reflect whatever politics are deemed correct in their time; they draw clear lines between good and bad, right and wrong. Even some of the more unconventional screenplay winners of the New Hollywood era—Chinatown, The Candidate, Patton, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, Annie Hall—follow many of these conventions. Consider the snubbing of Nicholas Ray’s soul-quaking In a Lonely Place (1950), featuring Humphrey Bogart as a mercurial scribe, the closest he ever came to being an antihero post-Casablanca. With its unnerving undercurrent of impending violence and its unusually unhappy ending, Ray’s film betrays its viewers’ desires. And another Bogart vehicle, Howard Hawks’s adaptation of Raymond Chandler's labyrinthian sleuth story The Big Sleep—whose mystery is so famously convoluted that even Chandler claimed to not understand it—received zero nominations.

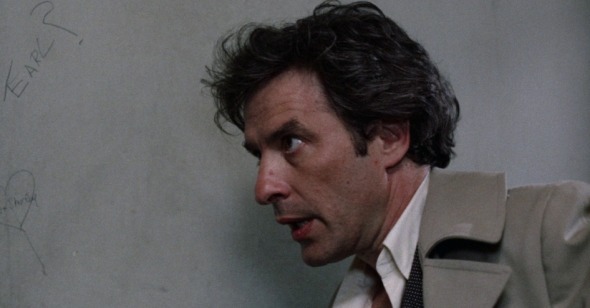

The ghost of Bogart hovers over two films from the 1970s that are screening in the Snubbed series, selections that exemplify the Academy’s indifference to unlikable antiheroes adrift in diffuse underworlds. The first is another Chandler adaptation: Robert Altman's deliberately uneventful 1973 The Long Goodbye, starring Elliott Gould as a mumbling Marlowe, an archaic relic from the noir days, now lingering languorously in early-’70s L.A. He does errands for his hot hippie neighbors; he wears wide lapels and drives a hunk of junk that would appeal to classic car enthusiasts if it were significantly refurbished and several decades later; his only consort is his persnickety cat.

The film begins with Marlowe just trying to be a good friend; it ends with him shooting his friend, and he loses the cat. A chivalrous loser, Gould’s Marlowe traipses about his apartment and trades barbs with the cops with wry tranquility, as if he knows that nothing he can say matters, as if the act of speaking is not worth wasting his energy. He's accrued a life’s worth of misfortune, always a day late and a buck short. His is a rumpled, unamazing, and indolent existence spent maundering about a world he might recognize and maybe even understands but about which he is apathetic.

As with The Big Sleep, the plot of Altman's film (adapted by Leigh Brackett) is of secondary importance. But Bogie’s dick is a guillotine-tongued wiseass blessed with that sardonic wit who never seems lost (even when the mystery is eternally elusive), while Gould knows as much as we do, which isn't much, and he never seems to be in control of any situation; this is not to say he's inept, but antiquated. Compared to the simmering suavity of Bogart, Gould is nearly somnolent, a forsaken soul in a sinful city. Marlowe is a dimming splinter of light in a dark, dishonorable world.

Like Hawks, Altman imbues and articulates Chandler’s novel with his own singular aesthetic—a weft of voices coalescing into one undulating mass of sound, and those lens zooms he loves so much, drifting lyrically, gently, not as artificially smooth as today's digital zooms; take, for instance, how he shoots Sterling Hayden’s boorish, bibulous Hemingway-esque scribe trudging toward the white-furled waves in the distance while Gould stands oblivious. There’s a dreaminess to the film, not unlike the oneiric air suffusing his 3 Women.

Another unsparing portrait of lonely men, Elaine May’s 1976 Mikey and Nicky, was also shunned by the Academy. Where Gould is laconic, torpid even, John Cassavetes is frantic and frenzied as Nicky, a loser doomed to die, a man writhing in mortal anxiety with only his treacherous friend, Mikey (Cassavetes’s real-life buddy Peter Falk), there to look out for him. That means he’s alone.

May’s film is an anti-spectacle—garrulous, largely comprising torrents of sad, paltry, ultimately futile words, garbed utterances of desperation, tragic because Nicky thinks they can help save him from his bosses in the mob who want him dead, and in its heart, the film is an elegy for one man who sees his own death encroaching, and doesn't realize that his friend, his loyal friend, is his Judas. It's one of American cinema's more empathetic portrayals of male vulnerability; Nicky is emasculated, useless in his insular world of violent men, all, in the end, out for themselves. We hope Nicky lives because he hasn't broken our moral laws, and Cassavetes instills the terrified guy with dignity, no matter how degraded he is. But the film makes it clear that he doesn't matter to anyone. We have to mourn him because no one else will.

Cassavetes struck up a lifelong friendship with Falk after they both appeared in Machine Gun McCain in 1969, and Falk then starred in Cassavetes's Husbands the next year, but Falk wasn't yet a film star (he was then, and probably always will be associated with his television role as Columbo, who always got his guy). Cassavetes, whose profile was substantially boosted after Rosemary's Baby, is the fed-up friend who betrays his buddy when the poor schmuck becomes too much of a burden. In one of the best episodes of Columbo, “Etude in Black,” Cassavetes—scheming, slimy, clubbing, killing, laughing, smirking—stares in disbelief at Falk, oddly amused and impressed at being outsmarted. Then, the two shake hands. There is no such respect afforded to anyone in Mikey and Nicky; there is no shaking of hands, no justice. (It's also worth noting that Columbo was wildly popular and earned accolades, while Mikey and Nicky, now a certifiable classic, passed like a fading phantom.)

Much like Coppola gave acting teacher Lee Strasberg his first major film role in The Godfather Part II, May offers the same opportunity to Sanford Meisner, who portrays the boss who wants Nicky dead, and has to convince Mikey to turn him in. The teacher’s method, dubbed the Meisner theory, emphasizes the importance of reaction, of dredging up genuine emotions from the bog of the heart with empathy through interaction rather than “becoming” the character. It's not about thespian histrionics, like so many of the big classic roles of the New Hollywood era. The best part is that May barely keeps him in the frame during his big scene. He doesn't get the glory, yet he is an ominous omnipresence, draped over the film like a horrible shroud stitched out of the same kind of pervasive corruption as in Altman’s film. Cassavetes was a Meisner man; he once showed up at the Actors Studio to give a purposefully histrionic performance and proclaim his disdain for the entire method before storming out. Falk’s brilliance was his ability to interact with everyone in the show's roulette of actors, always natural, effortless, never loud. But even Chandler’s sleuth gets closure at the end, or at least something similar in appearance, even though, to put it in popular terms, he doesn't "win." Nicky is no one; he dies a no one. And you wonder if and hope that Mikey is sorry. And you then wonder if that matters. Marlowe and Nicky are two men on their own, and the hearts of lonely men are heavier than dead bodies.