Decadent Degradation: Roger Corman and Edgar Allan Poe

By Greg Cwik

The screening series Haunted Houses and Terrible Tombs: Roger Corman’s Poe Cycle played at Museum of the Moving Image October 28–30, 2022.

“But as in ethics, evil is a consequence of good, so, in fact, out of joy is sorrow born.”

—Edgar Allan Poe

In October of 1849, 40-year-old Edgar Allan Poe, a prodigious drinker and lifelong loser, was found ambling about Baltimore, garbed in a stranger's garments and rambling incoherently. This, to those who knew of his incisive, eloquent prose and were aware of his assiduous attention to language and punctuation and dexterous sentences, replete with eruptions of unexpected vocabulary, must have seemed bizarre. This was not a man for whom the English language proved elusive. Broke, battered, and befuddled, he was unable to explain what happened. He died shortly thereafter and was not much grieved.

Poe is long dead, yet he lives on, his sordid spirit tethered to this Earthly realm by a vast legion of works derived from, and inspired by, however loosely, his baleful stories, all those musings of the morbid and macabre that were, to his agonizing dismay, abject failures in his lifetime, garnering him few readers and fewer dollars. That he, a self-proclaimed genius (and who today would even dare to object to such an assertion?), dawdled for a lifetime in penurious obscurity undoubtedly engendered the kind of melancholy that no amount of libation can mitigate. He made his piteous living writing guillotine-tongued reviews of other, more popular writers with great verbosity and vitriol and a prussic pen. (One of the few writers he openly admired was Nathaniel Hawthorne, dedicating two weeks’ worth of writing on the New Englander's debut collection of stories.)

What would Poe make of his status today as the master of modern horror and progenitor of detective fiction? As a pillar of the Western canon and his ubiquitous presence in worldly culture? Poe has profoundly influenced writers, notably the cryptic French poet Charles Baudelaire, who said that in Poe he had found his “literary soulmate,” and translated Poe into French to great acclaim, and H. P. Lovecraft, another writer of grotesque garrulousness who died in aching anonymity but whose afterlife has proven provocatively influential. The unceasing succession of works that Poe belatedly inspired is eclectic, and includes a Simpsons Treehouse of Horror parody of his poem “The Raven,” in which Bart, depicted as the vexing bird, torments Homer; an array of comics and pulps, mainstream and obscure, from the 1920s to the ’50s, in various degrees of faithfulness, most notably the EC Comics that Stephen King would borrow from freely; all kinds of stories and novels by the likes of Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, Marc Olden, Rudy Rucker, Kim Newman, Matthew Pearl, and so on; films by directors as diverse as D. W. Griffith, Antonio Margheriti, Edgar G. Ulmer, Freddie Francis, Mario Bava, Lucio Fulci, George Romero, and Dario Argento. (Perhaps the most loving depiction of Poe is his appearance in a key supporting role as a hallucinatory mentor to Val Kilmer's struggling, bibulous penman of trash fiction in Francis Ford Coppola's great Twixt, in which Poe elucidates on his method for writing, citing his famous essay “The Philosophy of Composition,” now considered a satirical work written for a lark, though Coppola treats Poe's pontifications with heartfelt earnestness: the sincere confessions of a man for whom writing was life, and for whom life was pain.)

Undoubtedly the most sustained and lavish cinematic project around Poe’s work is B-movie legend Roger Corman’s cycle of films based on the master's stories, released by American International Pictures between 1960 and 1964. Translating Poe to a visual medium is an inherently tricky endeavor: though the plots of his stories lend themselves to film, with their exquisite imagery of the eerie and evil, the everlasting poignancy of his work is his deftly diabolical use of language to conjure moods of ominous ineffability (“So violent a rudeness, untenanted by any tangible form," he says of the ruthlessly affluent Prospero in his 1842 story “The Masque of the Red Death,” a description that defies visualization). His is a sui generis sinisterness, an assault of adjectives and serpentine syntax, and a supreme rebuttal to the preference for simplicity in prose that would become trendy in the mid twentieth century. But Corman, like Baudelaire, found a kindred spirit in Poe. The films, shot in scope with luscious colors and crystalline compositions that belie their small budgets, are not literal adaptations, but amalgamations mingling different stories with the typical Corman touches and the elegant and unnerving elocution of recurring star Vincent Price.

Corman’s cycle, which began with 1960’s The House of Usher, based on Poe’s most famous story, 1839’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” came at the end of the atomic age, following a decade of films about giant ants and giant spiders, aliens descending on the otherworldly tonalities of theremins to warn us of the dangers of nuclear war or else out to destroy us. The cycle is aesthetically and tonally similar to the Hammer horror films, which began in earnest in 1957 with The Curse of Frankenstein and became tremendously popular the next year, with Christopher Lee's bloodshot eyes and insidious charm in Horror of Dracula. It was generally a major transitional period for horror around the world even beyond this. Hitchcock was at the apogee of his powers in 1960 with Psycho, and Michael Powell’s similarly voyeuristic (if less successful) Peeping Tom came out within months as well. In Japan there was the hallucinatory Jigoku, which would lead to an era of artsy horror like Kuroneko and Kwaidan, while the advent of Italian giallo was skulking on the horizon over in Italy with Mario Bava's Black Sunday hitting theaters (three years before Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much would usher in the genre).

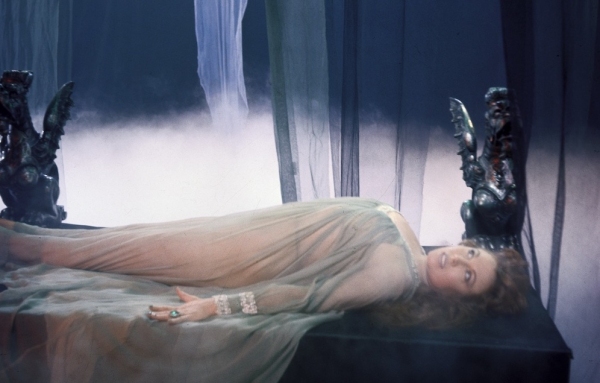

Corman’s films area product of their epoch, yet timeless, like Poe's work itself. Consider The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), which opens with a swoony display of vibrant colors, viscous variegation sloshing around the screen. Price plays Nicholas Medina, who, with his sister and servant, lives in a tumbledown terror of a castle, looming portentously on the eaves hanging over a thrashing sea, whose white-tipped crenellations are crashed upon by the waves like the throbbing of a terrified heart. The castle is pervaded by an unredeemed dreariness. Nicholas’s late wife (Barbara Steele, in all her enchanting pallor and hair as dark as pitch), seemingly haunts the castle, her ethereal voice perfusing the gray stone walls, beautiful and scary and beckoning. In the bowels of the castle is a ghastly array of torture devices, the toys of Nicholas’s late father, a place Nicholas calls the abode of the dead, a cavernous room of pain and torment, which we see early in the film; we spend the subsequent hour-plus waiting for them to spring to awful life, which, in the climax, they of course do. As in Poe’s completely different, Inquisition-set tale, the finale—the blade swinging back and forth, slowly, oh so slowly drawing nearer to its victim—makes manifest our cruelest inclinations, our horrible desire to see violence, to find in suffering a sense of fun.

Poe begins “The Fall of the House of Usher” by describing an “insufferable gloom” suffusing his spirit, but he took gleeful relish in his work, much of which he himself didn’t actually like. Corman and Price similarly strive not for ominousness, but a deranged sense of fun, with their vibrant colors and comely compositions. Look at The Raven (1963), which also opens with the dream-swoony swirl of colors, as Price intones over the shot of a bird before the credits with eerie placidity. Again, the mercurial sea, again a house of eldritch antiquity. If Corman repeats himself, that’s fine because Poe would sell a story to one magazine or paper, then sell it again and again to others in other regions, making minute alterations (modern editors have a tough time deciding which version is the definitive version of any given work). The opening act comprises a jocular conversation between Price and a bibulous, smart aleck raven, voiced by Peter Lorre, which may irritate those looking for Poe's solemnity, but keep in mind that Poe also wrote many humorous works—more than half of his fiction output. The man was not without wit, and not impervious to the allure of slapstick. After consuming a magic potion, the bird is transformed back into Lorre, so diminutive next to Price, his face sagging with decades of sorrow, and the pair team up to combat a minacious rival sorcerer, played by horror god Boris Karloff. The latter greets our motley cohort with Dracula’s famed “I bid you welcome,” but far more affably than Bela Lugosi's Count. The Raven is the silliest and most light-hearted of Corman’s Poe cycle, only tangentially related to Poe’s work, but it is also the funniest. There is, for instance, a scene of a big, bald brute of a man armed with an ax lumbering about until Price shoots green lasers from his fingers (!) to subdue him, and Corman cuts to a reaction shot of Lorre watching, head perched genially atop his hand, unperturbed. There’s also, quite humorously, a young Jack Nicholson as Lorre’s son, with a funny feather billowing up from his hat.

The 1962 anthology Tales of Terror—more massive, wayward buildings, the same irascible sea—draws from “Morella,” “The Black Cat,” “The Cask of Amontillado,” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar.” In “The Black Cat” (which is basically “Amontillado” with a slight tincture of “The Black Cat”), Lorre plays the embittered, boorish drunkard Montresor Herringbone; as in “Amontillado,” he lures the drunken jester Fortunato into the labyrinthine crypt of a building rife with barrels of booze and chains him up and seals the poor dumb bastard in a tomb of stone. We never find out why, but modern consensus agrees that it was spurred by some kind of innocuous insult. In Corman's version, Herringbone challenges Fortunato, a suave wine connoisseur played by Price, to a wine-tasting contest, in which the invidious boozehound matches Fortunato drink for drink until he's absolutely sloshed, and the erudite wine expert has to walk him home and consequently strikes up an intimate relationship with Herringbone's long-suffering wife. This is the reason for his horrible fate. It might seem like heresy to Poe fanatics that Corman changes “Amontillado” so severely, but it works, with a brisk 20-minute runtime that, unlike some of Corman's other films, never drags, and provides Lorre with his best role in decades. But in the end, the vociferous mewing of a pesky black cat, which Lorre loathes and insults with a variety of gleeful harangues ("You insufferable beast!"), gets Herringbone caught. The most significant and unfortunate difference between Poe and Corman is that the latter’s adaptations usually punish the main character for his digressions, whereas Poe had no scruples in letting the villain get away with it.

Normally, an AIP film was done in three weeks, but Corman's grandest and most faithful film, The Masque of the Red Death (1964), brewed with a bit of Poe’s “Hop-Frog,” took five weeks and had the largest budget of the cycle. Shot by Nicolas Roeg, it’s replete with crooked cameras and gentle distortions in the sides of the frame of the scope lenses. The colors pop lusciously, violently. Corman's film, like the story, concerns a plague ravaging the countryside while Prince Prospero (Price again, at his nastiest in a role that foreshadows Witchfinder General a few years later) invites his rich asshole friends to seek solace in his castle (for once, not wayward or derelict, but decorated decadently) for a masquerade ball. But an uninvited guest makes an appearance: Death, decked out in a crimson cloak. “There was much of the beautiful, much of the wanton, much of the bizarre, something of the terrible, and not a little of that which might have excited disgust,” Poe describes the saturnine party, and Corman indeed captures this grossly indulgent aesthetic, as noblemen guffaw at the poor peasants they use for amusement and dance in in their masks and robes. They don't know that their safe haven will soon become an abattoir.

"What terms shall I find sufficiently simple in their sublimity—sufficiently sublime in their simplicity—for the mere enunciation of my theme?" Poe writes in the beginning of his 1848 opus, Eureka, a glorious, prolonged diatribe against science, didacticism, and all the idiots and ingrates, the intellectual non-entities who failed to appreciate him. Simplicity is what Corman used to make his low-budget cycle, a simplicity that yearns for the sublime. There aren’t many special effects, little gore, and no bravado set pieces or camera maneuvers. Corman had to add to and alter Poe’s works to make 90-minute movies because Poe's fictive genius was in the short form. Consider The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, his only completed novel (he had begun to serialize another, but an argument with an editor lead to him abandoning the project), written for the money; it's mostly a slog, long tedious passages in banal prose, chronicling the quotidian endeavors of sailors, until the final few chapters, where Poe gets to flex his linguistic and imaginative muscles. He describes a diabolical descent into phantasmagoria and ontological awe that inspired the baroque metaphysical passages of Moby-Dick and Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, and works as recent as John Langan's The Fisherman. It's too bad Corman never got to make a film adapted from that.

There is no handy term for a work that is inspired by Poe, the way Lovecraft has Lovecraftian, Melville has Melvillian, Kafka has Kafkaesque; but Poe's mark on popular culture is undeniable. Perhaps better than any other filmmaker of the century, Corman explicates Poe's penchant for decadent degradation, the ethereal misery of the soul manifesting in the flesh: the crimson-cloaked cipher traipsing through Prospero's party; creepy Karloff descending the stairs to welcome his adversarial guests; all those terrible toys in the basement designed solely to maim and murder. And yet none of this is maudlin; it's all in good humor, which is how Poe would have liked it.