The Holy Grail

By Caroline Golum

Healthier, better-adjusted people than I might wax nostalgic about blissful months at summer camp, glory on the playing field, or extracurricular achievements. When I pan for gold amid the slurry of a turbulent adolescence, my girlhood at the New Beverly Cinema comes to mind.

In the salad days of my cinephilia, there was a loose circuit of Los Angeles institutions from which I’d get my repertory fix: the Hammer Museum at UCLA; LACMA for matinees during school vacations; and the gargantuan Egyptian Theater for roadshow Cinemascope epics. The audience skewed older, the screening rooms were spacious, and the shows were typically preceded by a lecture of some kind. There was precious little “hanging out,” and absolutely no food.

From our humble ranch-style home in the San Fernando Valley, my sainted parents would shlep me across as many as three freeways to Hollywood, mid-Wilshire, or far-flung Westwood. Our neighborhood wasn’t exactly a cultural backwater, but when an opportunity arose to attend an overcrowded arts-oriented public high school in West Hollywood, I was overjoyed. The prospect of commuting to a denser, more happening part of town was damn near the only thing keeping me grounded during four years of ennui and underperformance.

Across the street from my old alma mater was a “hip” cafe, whereby one could easily cop the latest issue of LA Weekly. Past the local news exposés, long-form cultural critiques, and restaurant reviews (all of which I dearly miss), I’d find the mother lode: movie listings, with ample column space for theaters I’d never heard of. And so, on a morning like any other—bored in homeroom, staring down another day of mental grunt work—I found my Holy Grail in a four-line listing for Monty Python’s absurdist medieval comedy at the New Beverly Cinema.

About that first outing, I remember everything: the unassuming marquee hanging over a peach-colored stucco facade, the shoebox lobby and even smaller bathrooms with their charming, if rickety, pre-war tile (and plumbing). The seats were worn, a few were sticky, but the layout was perfect—wide aisles and unobstructed sightlines. The concession stand sold popcorn, my beloved Raisinets, and sundry other treats at bargain-basement prices. The crowd was a healthy mixture of young and old, and I clocked more than a few “grown-up dates” in attendance. We laughed in unison, and when the lights came up, we spilled onto the sidewalk, all chatting animatedly apart but together in our shared excitement.

***

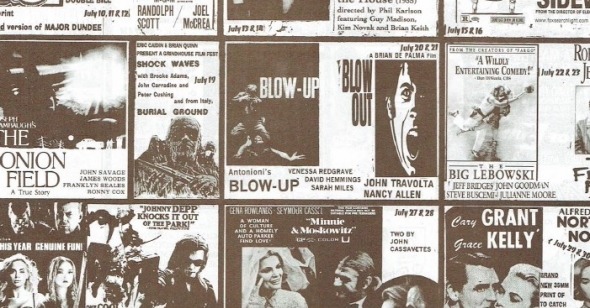

The New Beverly originally opened in the 1950s as “Slapsy Maxie’s,” a mob-friendly nightclub founded by heavyweight-turned-character actor Maxie Rosenbloom. In the 1950s it became the “Europa,” a legit cinematheque specializing in arty foreign titles, before pivoting to adult fare and rebranding as the “Eros.” It was in this somewhat sleazy iteration that longtime owner Sherman Torgan purchased the theater in 1977, rechristened it, and ran the operation seven days a week for the next quarter-century. On any given month, the calendar boasted a generous mix of grindhouse and art-house: Blaxploitation and ’80s slashers alongside The Virgin Spring or Breathless. And always on 35mm—first out of necessity, later out of novelty.

Over four years of filmgoing, I came to know Sherman as an omnipotent, benevolent fixture—his demeanor often reminded me of a kindly, old-time general store proprietor. His son worked the cash-only box office from time to time. Occasionally, I’d come up short a few dollars, and Sherman et fils would blithely look the other way. I even saw my first X-rated film there, just after my 18th birthday: Last Tango in Paris, the same salacious title that marked the theater’s official reopening in 1978. Every milestone of my young life—as an independent woman, but more importantly, as a cinephile—unfolded in this darkened sanctuary.

I mainlined “the Canon” before I even knew the term—we’re talking heavy-hitters here, the mother sauces of the Seventh Art. Citizen Kane, Rashomon, Jules and Jim, Barry Lyndon, The Apartment, each of these I encountered for the first time in a little rep cinema around the corner from Pink’s Hot Dogs. I’d come home, elated after another double feature—could’ve been Key Largo and To Have and Have Not or Pepe le moko and Bob le flambeur—and prattle on to my tired folks about a film they’d seen “years ago, when it first came out,” or “as a kid, on TV.”

Auguring an adulthood spent in New York’s rep houses, the New Beverly quickly became the nexus of my social life. I dragged one boyfriend to Abel Gance’s Napoleon, nudging him awake just in time for the tri-color-tinted finale. When we inevitably broke up a few months later, I consoled myself with back-to-back screenings of Nights of Cabiria and La Strada, sobbing in solidarity with Giulietta Masina’s downtrodden heroines. Shortly thereafter, confidence restored, I enticed another would-be suitor to a Sunday afternoon showing of Taxi Driver. During the climactic shoot-out, I played up my anxiety as an excuse to grab his hand. One summer a friend from LiveJournal (remember her?) came down to Los Angeles on a prospective college tour, and I proposed a double feature of Duck Soup and Horse Feathers as the safest possible meeting place. Surely, if I went missing, the attendants at the New Beverly would notice my absence.

At peak attendance, I was averaging three screenings a week—sometimes with a date or with girlfriends, but just as often alone. Unfettered by school, an uncertain future, or the world at large, I’d plop myself down fourth row center: just me, my popcorn, a sketchbook, and my feelings. Even if I already had one, I’d grab a calendar from the plexiglass box out front, circling the must-sees coming up and cutting out pictures of my favorite stars. I’m loath to refer to this period as the happiest in my life—who wants to admit to peaking in high school?—but frequent, inexpensive filmgoing remains to this day my vision of perfect bliss.

My first summer back east was woefully, foolishly spent without air conditioning, and I’d yet to discover bars, clubs, or the usual ways in which people meet people. The seeds sewn back on Beverly and LaBrea bore fruit during those months at MoMA, Anthology, Film Forum, and other venues in the exotic “outer boroughs.” I expanded my purview and dipped into more “obscure” fare, a little too pleased with my “mature” taste and dismissive of the “101 stuff” I’d already absorbed at the New Beverly. I started reading film criticism in earnest—we never had to read it for class—in the pages of Film Comment, The Village Voice, and, incidentally, this very website.

I’d counted on the New Beverly to wait for me, like a faithful dog, while I metamorphosed into the kind of person who made off-the-cuff references to André Bazin and Béla Tarr. Whenever I got around to visiting Los Angeles, there it would be, unchanged and ready to receive my six bucks. This naive notion was shattered in 2007 when, one July afternoon, my dad called me in the middle of the day. “I have some sad news,” he said. “Sherman—you know, from the New Beverly? He passed away this week.” At 62, on one of his usual bike rides through Santa Monica, Sherman Torgan died of a heart attack. Months later, visiting for the holidays, I saw his son behind the box office. When I offered my condolences, he replied that his father was always surrounded by friends—and expressed dismay at his dying, surrounded by strangers, steps from the glistening Pacific. Then, he sold me a ticket with my old student discount.

***

In Sherman’s absence, the future of the New Beverly looked grim. Developers circled what had become a ripe investment prospect: a single-story building in an increasingly gentrified part of town. It’s old hat by now, as old as the city itself, but in true Hollywood fashion there’s always a chance some deus ex machina will save the day. Having changed hands from a coterie of mobsters to an aspirational film society, from a film society to a smut peddler, and from a smut peddler to a family man and movie fan, the story of the New Beverly still had one chapter left.

This time, it was a famed former video store clerk-turned-auteur who, in late December of that same year, swooped in and saved the cradle of my cinematic infancy from certain destruction. When news broke that Quentin Tarantino purchased the New Beverly, I feared once more for its future in Los Angeles’ delicate repertory ecosystem. The first post-Sherman calendars leaned more than usual on grindhouse titles from Tarantino’s private collection, and his own work screened every weekend without irony. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood enjoyed a two-month stint throughout July and August of last year. The website prominently lists “Tarantino Reviews” and “Quentin News” above the fold—wholly separate from their blog—alongside the calendar and contact information. Ultimately, I’ve had no choice but to make my peace. Better to keep the theater doors open, at the expense of its mom-and-pop scrappiness, than let it disappear forever.

A year after Sherman’s passing, I was outside a bar on Broome Street, cribbing a smoke from a chatty young woman. She recognized my face but couldn't quite place it. Expecting an off-the-mark celebrity comparison, I was shaken to my core when she exclaimed: “I know you! You’re the New Beverly Girl!” The way she said it, like “the Time to Make the Donuts Guy,” or “the Sun-Maid Raisins Lady”—it had such gravitas, as though this honorific were part of some parallel pop culture universe.

After a few minutes of Jewish geography, I discovered that my bubbly interlocutor was in fact a former box-office attendant at the New Beverly. Between shared reminiscences, she made an offhand remark that continues to haunt me more than a decade later: “We were going to offer you a job, but you moved away.”

I don’t regret much, but this exchange whispered into me something akin to remorse—a vision of an alternate life in which I drive a car, come home to do laundry, and work full time at my favorite repertory cinema. I stewed over this prospect for days. If memory serves, I was still a recent transplant, maybe two years tops.

I’ve spent my entire adult life pin-balling between New York City’s repertory cinemas; haunting MoMA matinees during stretches of unemployment, working up the chutzpah to pitch programs to venues large and small, rolling deep and hoarding seats at 12-hour marathons, fine-tuning my taste and cultivating lifelong friendships all the while. I’ve even managed to find work—on a volunteer basis, of course—at my favorite movie theater. But whether I’m surreptitiously sipping a seltzer in Titus 2 or putting my feet up on a balcony rail, I’m still proud, and always will be proud, to be the “New Beverly Girl.”

Reverse Shot is a publication of Museum of the Moving Image. Join us at the Museum for our weekly virtual Reverse Shot Happy Hour, every Friday at 5:00 p.m.