Intermission

By Susannah Gruder

It would be an understatement to call BAM my home cinema. In reality, it’s my home-away-from-home. To get to the screening rooms, you enter the lobby (its vaulted ceiling and intricately patterned tile floor no less imposing than the building’s terra cotta Beaux Arts exterior) and into the cinemas on the far left side. Tucked on the opposite end of the lobby, however, inside a vestibule that opens onto the 2,100-seat Opera House, is a door that leads to my mom Christine’s office, where she works as the Theater Manager for BAM’s live productions (on hiatus along with all shows at the Cinema). She’s been at BAM for 32 years, and as a kid I’d visit her during the day before the evening’s performance began, running through the empty house, jumping over seats, pretending I belonged to a rich, possibly royal family, and that this was simply one of the rooms in my extravagant home. The box seats were my preferred spot for playing hide-and-seek with a friend or my little sister. I was on good terms with the stagehands, who’d occasionally let me ride in the genie lift as they set up for a performance by The Royal Shakespeare Company or Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal. For years I was too young to appreciate most of the artists who graced BAM’s stage, but my connection to the space itself was, and is, profound.

Now that I’ve matured a bit, the programming at the cinemas and theaters at BAM has become meaningful to me as well. I’ve seen so much at BAM that each moment in the lead-up to a film or performance has grown exceedingly familiar. I can picture Adam, the Cinema Manager, coming out to jovially report that “This is a sold-out show, so get cozy with your neighbor because every seat will be filled.” Or my mom’s voice coming through the lobby’s overhead speakers as the lights flash on and off, announcing that the performance will begin in ten minutes. And then there’s that split-second of darkness. In the cinema, it comes between the last trailer and the film you came for. In the theater, just after the house lights dim completely. It’s a feeling of being on the threshold of something unknowable—the last moment you can say to yourself that you’ve never seen what you’re about to see.

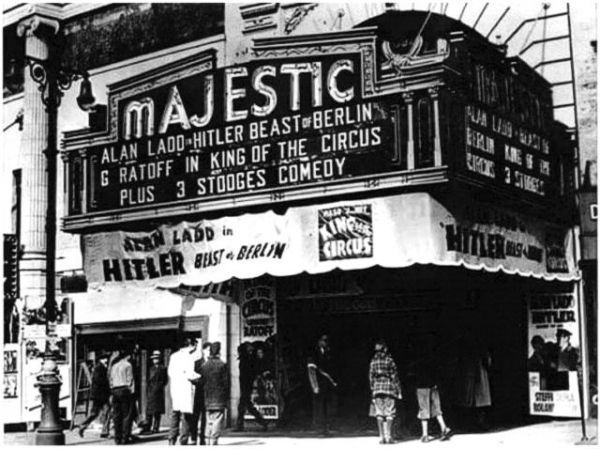

When BAM opened the Rose Cinemas in 1998, they were the first in the country to have a multiplex cinema within a performing arts center. What was once the Carey Playhouse, home to BAM’s smaller productions, became a movie house, with Cinema 3 maintaining the playhouse’s dramatic proscenium, a glorious remnant of its former self. BAM has a long history of converting theaters into cinemas, and vice versa. What is now BAM’s Harvey Theater a few blocks away on Fulton Street was once the Majestic. Built in 1904, the Majestic was a first-run movie theater between 1942 and 1968, and before that a vaudeville theater (not to be confused with the theater in the 2001 film, The Majestic, in which Jim Carrey plays a time-traveling screenwriter who helps to renovate a similarly decrepit movie house). It sat in disrepair until 1987, when BAM took ownership and turned it into a fully functioning theater, keeping its interior in a state of fossilized ruin. In 2013 the Harvey debuted their new Steinberg screen, which would host large-scale screenings of epic films like Black Panther and Star Wars. The Opera House itself has hosted screenings of films like Phantom Thread and Voyage of Time with a live orchestra. All this shape-shifting has resulted in a comforting feeling of flux, affirming the notion that a cinema and a theater are one and the same, and the work that’s presented in each are of equal value.

This idea found its perfect expression for me one weekend in 2013 during BAM’s three-day festival Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, which brought together music, art, and film screenings across their various venues. At one point I wandered from a Julia Holter performance in the Opera House into a screening of Matt Wolf’s I Remember: A Film About Joe Brainard, which had already begun. (The festival was such that you were encouraged to step in and out of each event at will.) Wolf’s film features an audio recording of Brainard, the queer writer and artist reading his 1975 poem “I Remember,” interspersed with recollections from his friend and collaborator Ron Padgett. Brainard worked largely in collage, and the film itself becomes a sort of scrapbook of memories that commingle to create a unique portrait of the artist. “I remember the different ways people have of not eating their toast crust,” Brainard recites. “I remember when both arms of your theater seat have elbows on them / I remember (spooky) when all of a sudden someone you know very well becomes momentarily a total stranger.” It was a moment of discovery—of Brainard’s words, themselves a form of nostalgic self-collage; of his art, which appeared on-screen; and of the assemblage that Wolf had created from the fragments of Brainard’s life. It was also one of the first times I’d felt comfortable entering a film late, for it felt as though it could loop forever, gently summoning up memories that are meant to go in one ear and out the other.

Wolf’s mode of filmmaking spoke to me then, and continues to do so—as a writer, I relate to the way he deconstructs the lives of other artists, like Arthur Russell in Wild Combination, or of obsessive collectors, like Marion Stokes in his recent Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project, and uses these pieces to reassemble a faithful portrait. Filmmakers like Sam Green work similarly, and it was a 2013 performance of his “live documentary” The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller, a study of the inventor and futurist featuring live music from Yo La Tengo and live narration from Green at the Kitchen, that prompted me, fresh out of college, to “publish” my first attempt at film criticism on my now-defunct Tumblr. Perhaps it’s my generation’s penchant for sites like Tumblr and Pinterest that draw many of us to this kind of mixed-media, where seemingly disparate images and ideas can exist alongside one another, their juxtaposition at once chaotic and calming.

The notion that cinema can be an event on par with a live performance is something I believe even more firmly now that going to the movies is no longer an option under our stay-at-home restrictions. I’m relatively well-prepared for these conditions, having grown up with a weekly routine of visiting my local video stores—the higher-brow Cinematheque and Video Forum on 7th Avenue in Park Slope, where at 14 I’d rent films like Persona and Y tu mamá también to watch in my room with a glass of wine I’d surreptitiously poured; Blockbuster on 5th Avenue for sleepover-appropriate horror movies like The Omen and Cabin Fever; and the Brooklyn Public Library for episodes of The Avengers on VHS (the über-mod ’60s TV show, not the Marvel movies), which I’d watch with my dad on summer days.

More recently, however, I’d become familiar with the idea that certain films have to be seen in the theater. For most of my life, going to the movies was an activity to do with friends, and I’d never seen a movie alone (except for one instance when a friend got confused about movie times and left me on my own to miserably watch The Core.) The Park Slope Pavilion, with its bright purple seats, was a few blocks from my house, and the majority of my middle-school class would often be in attendance at films like Spiderman and Spiderman 2, Mean Girls, and Austin Powers in Goldmember. When I went to high school in Lower Manhattan, we’d go en masse to the Regal Battery Park to see Superbad and Casino Royale. My French class friends and I discovered Christophe Honoré’s Love Songs at the IFC Center somewhat by chance, sparking an obsession with his lyrics (and Louis Garrel). When I spent my junior year of college in Paris, I winced along with friends through Inland Empire in the salle Henri Langlois at the Cinémathèque Française, and frequented the tiny Le Desperado cinema in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, which mostly played American films we’d never heard of, like What’s New, Pussycat? I remember the people I was with as clearly as the movies themselves.

Growing up, my dad would often tell me about how, when he was 14, he went to see Sergei Bondarchuk’s seven-hour War and Peace alone at the Ziegfeld, and that during the intermission they served champagne and caviar. I’ve always longed for this kind of experience, where going to the movies is as momentous as seeing a Broadway show. I didn’t quite receive that treatment during the intermission of Shoah (10 hours) at the Quad, or La Flor (14 hours) at NYFF, but I did develop a sense of endurance, and an enjoyment of coming to the theater by myself, that I hadn’t known before. Perhaps it’s because I’m still fairly new to film festivals, with my hopeful naiveté about Sundance and Tribeca still intact, but now, seeing three movies back to back, with 15-minute breaks in between, as I’ve done a few times now, is my idea of heaven. It turns out that catharsis on top of catharsis can be, in fact, a good thing—the emotional release tends to build exponentially for me. I soon began to seek out this feeling, returning to IFC for each episode of Kiarostami’s Koker Trilogy, even though I’d only intended to see one. I cried, alone, at the ending of each; I’d never been happier. Going to the movies with people was always an event. But it was here, standing alone in tears outside the IFC, that I realized it could be significant, maybe even more so, when you’re on your own.

I’ve been to these theaters so many times that I can reconstruct their interiors perfectly in my head—IFC, Film Forum, Regal Union Square, the Walter Reade, Metrograph, MoMI, Spectacle. There’s no space I know better, however, than BAM, its cinemas and theaters sitting together side by side, projecting a harmony between the seventh art and all the rest. My memories of the music, dance, and theater I’ve seen there remain as well, coexisting alongside those of the films—Mark Morris together with Chantal Akerman; Ivo van Hove next to Franco Rossi. All of these images work to form a patchwork that keeps me company while I, along with everyone else, wait on the threshold of whatever comes next—almost like waiting for the movie to begin.

Top: The Helen Carey Playhouse—now the BAM Rose Cinemas—pictured in 1907.

Bottom: Built in 1904, The Majestic—now BAM's Harvey Theater—which served as a first-run cinema and a vaudeville theater in Brooklyn's Fort Greene neighborhood.

Photos courtesy of the BAM Hamm Archives.