Many of Reverse Shot's writers and contributors come from and reside in locations all over the U.S. and beyond. Escape from New York is a column devoted to reminding us Manhattan-and-Brooklyn-centric moviegoers that we are not the world when it comes to cinephila.

Night at the Museum

by Daniel Witkin

Moscow’s disparate film viewing options are well integrated into its surreal, schismatic landscape. For instance, a Western-style upscale independent theater has popped up down the block from Yuri Kuklachev’s Cat Theatre, home to a famed Soviet-era clown who manages to blend neo-Orthodox life lessons and trance beats with feline acrobatics. A viewer more interested in older fare may find herself on the ground floor of the palatial Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building, the most centrally located of the “Seven Sisters,” Stalin-era stone skyscrapers that rise out of the landscape like cathedrals to a certain secular ideal. As nostalgia has grown for both Soviet and imperial times, replicas of both these buildings and their Tsarist forebears have appeared throughout the city, but some new works resist pre-existing categories. For instance, alongside Muzeon Park, which hosted outdoor screenings of Soviet avant-garde classics this summer, one encounters Zurab Tsereteli’s humungous statue of Peter the Great, which manages to pay tribute to many aesthetics—imperial idolatry, Soviet monumentalism, and Disneyland kitsch, while remaining palatable to none. Constantly showcasing, regurgitating, and defacing its often contradictory history, the city appears as an Eisensteinian montage of attractions in four dimensions, a dialectic out of control.

Similarly striking juxtapositions can be found among audiences themselves. Repertory, festival, and art house screenings are certainly attended by hardcore cinephiles, both internet-savvy youths in Brooklynesque garb and grizzled older types, but also cater to a broader cross-section of society than one might expect. In general, Russians have an intensely reverent but demanding relationship with art, and these demands can manifest themselves in unexpected and sometimes amusing ways. At a director-attended screening of Sharunas Bartas’s Three Days, a group of older women became intent on knowing why the film’s female protagonists were so “strange.” When the Lithuanian director attempted to politely rebuff the question by philosophically musing on the normal and the human, he was firmly informed that, no, those young women were indeed “odd” and “unusual,” as well as “atypical.” Later, a viewer responded to a similarly noncommittal Bartas answer, this time about the unknowability of the creative process, by bluntly saying, “I don’t believe you.”

For the most passionate of Moscow’s moviegoers, Russia’s Cinema Museum, officially the State Central Museum of Cinema, occupies a crucial place in the city’s cultural world. The museum was founded in 1992, immediately after the fall of the USSR, as the abdication of ideology was quickly followed by an inundation of commercial goods and mass culture. What had developed over decades in the West was dumped on Russia seemingly overnight, and citizens were forced to wonder how their country’s psychic landscape would be altered by the sudden preponderance of the flashy, instantaneous, and the disposable. The once robust and self-sufficient Soviet film industry all but collapsed, losing its state patronage at the moment that the country was opened to foreign competition.

The museum’s collection was created from virtually nothing by Naum Kleiman, a charismatic film scholar and global authority on Soviet cinema who visited filmmakers and their families to examine their personal collections. Alongside the museum’s archival activities, Kleiman engineered plentiful and varied screening programs at the museum’s headquarters in the Krasnaya Presnya Park, which became Moscow’s de facto cinematheque, replete with a Dolby Surround Sound system gifted by Jean-Luc Godard. As the Russian film industry underwent a period of total decline, the museum helped to secure the tenuous connection between the Soviet past and uncertain present, screening both canonical and overlooked classics of Soviet cinema alongside their international counterparts, many of which had been impossible to see under Soviet rule. Their efforts constituted one of the first and most serious systematic attempts to present Russian and Soviet cinema to a public audience as part of global culture.

This iteration of the museum, sadly, was not to survive in Russia’s fickle cultural market. As the country adapted to occasionally literally cutthroat capitalism, cultural institutions, even public ones, were pressured to behave like private businesses or, often, speculators. Even as the government of new president Vladimir Putin bombastically undertook grand projects to signal the end of the humiliating nineties, the quiet excellence of the cinema museum fell out of favor. One official deemed it, “a place for dopeheads and young punks.” In 2005, the authorities stood by as it was evicted by Nikita Mikhalkov’s director’s union as part of an elaborate and lucrative property transaction. “We were naive to believe that in such a short time this country would change for the better,” Kleiman told The Guardian, “The ghosts of the past are still very much alive.”

The museum was now dispersed throughout Moscow—the archives were moved to the headquarters of Mosfilm and screenings and exhibits were held at various venues throughout the city. Yet despite the obvious handicap of lacking a unified space, the museum was able to continue operating at a very high level, largely due to the devotion of its staff. Kleiman was joined by film scholar Maxim Pavlov, who quickly became an able co-leader of the museum's day-to-day affairs. The museum garnered international recognition—in 2007, Kleiman won an award at the Venice Film Festival “for his contribution to the preservation of Russia’s cinematic heritage,” and the museum maintained its reputation as one of Moscow’s most intellectual institutions.

While retrospectives and festivals take place on and off throughout the year, the Cinema Museum is the most reliable place to see well-curated repertory films. It is the place where one is likely to find a film by Satyajit Ray, Carl Theodor Dreyer, or Alexander Dovzhenko. In addition, the museum plays a role in many other cinematic and cultural events, from international programs to screenings with live music. Its 35mm screenings in the Mossoviet center, which it shares with a competitive ballroom dancing center (“the dance spirit of the capital!”), are always genial and cozy, and begin rigidly on time.

*****

Contemporary international cinephilia is at once cosmopolitan and cloistered. Cinephiles today pride themselves in seeking out films from all corners of the world, which tend to be mediated through a small number of lushly financed festivals dedicated to the lofty postwar ideal of “cultural exchange,” though by necessity featuring many of the same films and individuals. Those prevented by resources or geography from traveling the festival circuit may experience it vicariously, usually over the Internet. As an activity and community, cinephilia is at once a sort of utopian respite from the modern globalized world and a reflection of its values and practices. The Russian cinephile must balance this tension while also contending with a state whose rhetoric—lots of compulsive talk of “self-definition,” “sovereignty,” and “autonomy”—speaks of a haphazard attempt to extricate itself from this larger world; or, at least to engage with it only on its own terms. As it’s struggled to maintain its independence and possibly its existence, the Cinema Museum has had to navigate between the idealized cosmopolitanism of international film culture and its country’s increasingly tenuous relationship with the outside world.

While the museum had previously been able to manage this tenuous dynamic, recent events have elevated it to the level of existential threat. Though this conflict came to fruition only recently, its foundation was laid in July 2013, when the Ministry of Culture decided not to renew Kleiman’s contract as director of the museum. This move was met with such outcry, including a petition signed by members of both the Russian and international film community, that he was brought back for a one-year term. In the intervening year, however, the mood of the authorities began to shift. As Putin stewed over the protests of 2012, which left him feeling betrayed and isolated by international powers, his rhetoric of Russian geopolitical resurgence and traditional identity became sharper and more prominent, exponentially more so after a new round of pro-Western protests broke out in neighboring Ukraine. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Putin’s newfound focus on Russian identity and tradition has had ramifications for the country’s cultural life, which in Russia is no secondary matter. Throughout all the lacerating discontinuities in Russian history, one constant has been an intense passion for art, seen as a key part of the country’s social as well as cultural fabric. As a popular expression proclaims, “Pushkin dlya nas vsyo” or, “Pushkin for us is everything.”

At present, the man answerable for Pushkin’s legacy is one Vladimir Rostislavovich Medinsky, Minister of Culture. The story of Medinsky’s rise is not atypical for a politician of his generation. After working as an ad man in the go-go nineties, Medinsky became an early member of Putin’s United Russia party, working as the head of Moscow operations before being elected to the Duma in 2003. Throughout his political life, he has maintained a parallel but not unrelated career as a particular sort of historian, penning a series of books called Myths, in which the now-Minister exposes as Western slander such ideas as Ivan the Terrible’s poor human rights record and Russia’s legacy of anti-Semitic violence. In 2011, he completed a Ph.D. dissertation in History, whereupon he was faced straightaway with widespread accusations of plagiarism.

In April, Medinsky’s Ministry of Culture released an interesting twelve-part document called “Materials and Propositions for the Project of the Foundation of Government Cultural Policy,” rather boldly announcing, “Russia is not Europe.” The consequences of this idea are best elaborated in part six, entitled “It is necessary to include in our document a thesis on the refusal of multiculturalism and tolerance.” Here, the writers bemoan the perceived “legitimization of any form of behavior, regardless of its admissibility to the culture and system of values common to Russian citizens.” What is needed, then, is the active state promotion of a “unified cultural code.” While direct censorship is deemed fair game, the authors offer the quieter channeling of resources as a more elegant alternative. To this end, Medinsky himself is quoted, “Let one hundred flowers grow, but we will water only those that are helpful to us.”

Moscow’s cultural life has been chugging along, but anxiety is growing amongst Russia’s more independently or critically minded artists. One new law, for instance, bans the release of materials that depict cursing, giving the authorities the legal grounding to block a number of important Russian films and plays, if they so desire. While this law, like many similar ones, is haphazardly enforced at best, it serves as a well-understood reminder of the state’s ability and willingness to intervene where it sees fit.

In June of this year, Kleiman’s new contract was also allowed to expire, but he was brought back as the museum's president, a newly invented post with ambiguous responsibilities, to serve alongside Larisa Ottovna Solonitsyna, the new director. The daughter of renowned actor Anatoliy Solonitsyn (you may remember him from such films as Andrei Rublev and The Ascent), Solonitsyna had previously worked as the editor of SK Novosti, the newsletter of Mikhalkov’s director’s union. She was known to be close to Mikhalkov, who, in addition to his roles as director and union chief, also runs the Moscow International Film Festival and is known as a major mover-and-shaker in Russian pop culture.

On October 14, the workers of the cinema museum entered into open conflict with their new management, formally expressing their distrust for Solonitsyna and demanding her removal in an open letter to figures in both the Ministry and the Kremlin. Solonitsyna’s tenure had begun inauspiciously, with the unilateral and unexplained firing of Maxim Pavlov and an attempt to institute a more rigidly bureaucratic organizational structure. The workers were also anxious about her interference in other aspects of the museum's work. For instance, the collective revealed that Solonitsyna had made a last-minute decision to withdraw the museum’s involvement in a program of ethnographic films by Lennart Meri, the first president of Estonia, co-sponsored by the Estonian embassy, on the grounds that “the topic of Finno-Ugric people did not fit the museum’s profile.” She also announced plans to orient programming towards movies with “family themes” and to more closely monitor the balance of “native” and “foreign” films. For those keeping score, Alexander Dovzhenko was placed in the latter category.

The Russian media paid some attention to the museum collective’s first letter, but it wasn’t until Kleiman and his staff quit in protest on October 27 that the museum’s plight became a prominent news story. A spin war immediately broke out. The museum workers insisted upon the impossibility of working with their new manager, while Solonitsyna publicly questioned their seriousness and professionalism. Suddenly, a report accusing the museum’s old management of misspending funds surfaced and disappeared. Each side accused the other of blackmail. Throughout the Russian cultural landscape, major figures began taking sides and assessing potential consequences. Medinsky and Mikhalkov aligned themselves with Solonitsyna, while the country’s major film journals and an alternative director’s union run by Boris Khlebnikov and Alexei Popogrebsky supported Kleiman. The museum workers even found a supporter in the Kremlin in the mythically named Vladimir Illych Tolstoy.

Tolstoy, an advisor to the president and the great-great-grandson of a certain well-known writer, briefly became the museum’s most influential ally. After the collective’s announcement, he went on record saying that the authorities “must not allow the mass resignation of the museum’s staff.” Together with Mikhail Bryzgalov, a high-ranking ministry official, Tolstoy organized a meeting between the collective and their new management. Though heated, the meeting offered little progress. The international community attempted to intervene as well. On October 30, Sight and Sound posted an open letter in defense of Kleiman from Mark Cousins, Thierry Frémaux, and Tilda Swinton, who were quickly joined by major luminaries from throughout the cinematic world. Yet while a similar petition helped Kleiman to secure his position a year earlier, international influence would be more limited in the current political climate.

As the conflict grinded to a stalemate, ever more elaborate rumors began to circulate. Many at the museum and in the media suspected that Solonitsyna’s old boss Mikhalkov was manipulating events from behind the scenes as part of an elaborate power grab. Mikhalkov had announced his intentions to build a grand “festival palace” for his Moscow International Film Festival, to which the museum might make an attractive addition. Some murmured about vague plans to open a branch of the museum in a high-profile, if troubled, new Russian territory: Crimea. Meanwhile, Kleiman held tentative discussions with Marina Loshak, the director of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, who had shown interest in adding a cinematheque along the lines of MoMA or Washington’s National Gallery of Art, about the possibility of a merger.

After more than a week of dead ends and confusion, Kleiman himself broke the stalemate. Through a series of emotional, behind-the-scenes appeals, Kleiman convinced his staff to abandon the mass resignation he had organized and return to work on November 10. For the most part, the workers heeded his call, though some younger employees elected to leave for good rather than continue working under the new management. The purpose of this fraught decision was to protect Russia’s most important film archive, which might be damaged beyond repair if left to a new staff of unknown ability. Yet Kleiman himself elected to leave the museum rather than remain in a post that had turned out to be entirely ornamental. On November 11, he released a letter in which he thanked his international supporters and promised to continue fighting for his staff. “Love is much more powerful than self-interest and suspicion, pettiness and vengefulness, thirst for power and brute force,” he wrote at the end of his letter. “We have learned this from the cinema, whose treasures, we are sure, must be preserved for the future and shown to the present.”

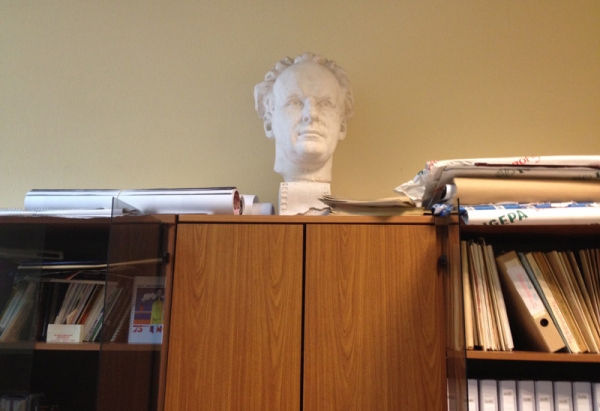

After an extended communication, I finally managed to get into the museum’s offices on Kleiman’s last day. Lacking a real exhibition space, the museum’s impressive collection is bottled up somewhat awkwardly in an unremarkable office among the soundstages of Mosfilm. Still, the space was striking, combining the otherworldliness of film sets and the outside-of-time atmosphere of museums. Outside, some of the museum’s researchers and programmers smoked alongside an actor in full Nazi regalia. Despite the grim circumstances, namely, being removed from a museum that he effectively created and at which he had spent more than two decades of his life, Kleiman was in good spirits. “Oh, I loved Chris Marker!” he exclaimed upon unearthing a letter ornamented with a drawing of a cat. By the end of the day, all that was left on his desk and bookshelf was an oversize bust of Sergei Eisenstein.

In the evening, the museum workers held a small birthday celebration for Anya Bulgakova, a filmmaker and researcher at the museum. Kleiman gave the speech, speaking of his love for his staff, their magnificent cohesion, and the importance of perseverance and optimism. Having lived through a number of iterations of his country, Kleiman brought to his cadences a certain understanding of the bizarre cycles of Russian history, their jump cuts and rhythmic irregularities. What exists in Russia may change quickly with little warning, and throughout the country's history this has remained a source of consuming anxiety and perversely durable hope. Solonitsyna was not present at the celebration, but remained sealed in her nearby office. Throughout the afternoon, she did not emerge once.

*****

Much of what one reads about Russia makes it out to be a spooky and inexplicable kind of place. As Winston Churchill once famously said, “Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” But a shroud of mystery can become a sort of arbitrary boundary, much like the facile cultural generalizations currently being exploited by the Russian authorities to buttress their shaky ideological foundations. Instead of encountering Churchill’s burrito of obscurity, the attentive Westerner will find much in Russia that is strikingly—if sometimes depressingly—familiar. As the situation in Eastern Europe codifies, expect to hear a great deal of warmed over Cold War rhetoric about Russia’s embarrassing predilection for despotism and how poorly this compares with our way of life. While the fate of Moscow’s once excellent film museum can certainly be tailored to fit this narrative, it ultimately matters most because of the museum’s work itself, cinema, and its ability to undermine these barriers by emboldening us to look more closely at life and trust what we find.

Photos by Daniel Witkin