The New Frontier, Same as the Old Frontier

Eric Hynes on The Right Stuff, Reds, and Paris, Texas

We are too great a nation to limit ourselves to small dreams… We have every right to dream heroic dreams. Those who say that we're in a time when there are no heroes, they just don't know where to look.

Ronald Reagan’s First Inaugural Address, January 20, 1981

The received wisdom about American cinema in the 1980s is that it was an artistically barren time, a creative comedown after the “maverick” auteurist pinnacle of 1970s. The seeds of blockbuster culture planted by Jaws and Star Wars grew into a hegemonic forest of Spielberg, Lucas, Stallone, Schwarzenegger, Zemeckis, and Reitman, and sequels upon sequels. It marked the end of personal cinema and idiosyncratic artistry on a grand scale, ushering in the bifurcation between Hollywood and independent cinema that persists today. The budgetary bloat and reactionary ideology of the country’s cinema (Rambo, Red Dawn, etc) neatly and tellingly harmonized with the country’s Reaganite politics. As David Bordwell wrote in a defense of the decade in 2008: “Like big hair and padded shoulders and Wham!, the films of the 1980s are apparently something to be ashamed of.”

Although much of the above has traction in reality, the truth, as is truth’s wont, is more complicated. For all of the corporate consolidation and crass opportunism, it was also a time of big-stage, tough-sell passion projects—especially among 1970s-hewn auteurs who were undeterred by an industry supposedly inhospitable to risk, from Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun to Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, Coppola’s Tucker: The Man and His Dream, De Palma’s Casualties of War, and Lucas-Henson’s The Dark Crystal. Yes, there was Friday the 13th Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan, but it was also a time when David Lynch and David Cronenberg were entrusted with the biggest-budgeted projects of their careers, and when incomparable masterpieces like Tootsie and Full Metal Jacket arrived irrespective of their Cineplex neighbors.

And it was also a time when the contradictions and conflicts within both the industry and the national ideology could themselves be explored on the big screen. The 1980s were rife with cinematic Trojan horses that proved more troubling and complex than their packaging, or pop cultural context, would indicate. Witness Warren Beatty’s Reds (1981), a self-scrutinizing romantic communist epic that, by turning up mere months after conservative savior Ronald Reagan’s electoral landslide, is perhaps the most politically countercultural Hollywood movie ever released; Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff (1983), a shaggy-dog dissertation on our twinned taste for individuality and collectivism disguised as a pro-NASA prestige picture; and Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas (1984), a road movie melodrama that simultaneously dismantles and exults in the myth of the taciturn western hero, These three films in particular explored the dawn of the Reagan era as a time for reimagining and reevaluating the American frontier—in borders actual and imagined, ideological and metaphoric, collective and personal. To scramble Reagan’s own words, they each interrogate our heroic dreams, and honestly consider the costs of America’s “greatness.”

It may not be the first genre that comes to mind when you think of the 1980s, but as with the 1950s—another deceptive era, usually deemed "reactionary"—three-hour historical epics had a strong foothold throughout the decade, most notably with best picture Oscar winners Gandhi and The Last Emperor. But though The Right Stuff and Reds certainly qualify as epics—each was long enough to justify an intermission, and each spanned a crucial era in 20th century history—they’re also exceptionally odd ducks, formally frisky endeavors by radicals eager to torpedo whatever reverence the venerable genre invites.

Reds may be remembered in part for its bifurcated docu-dramatic storytelling gambit, but thanks to the onscreen participation of Diane Keaton, Jack Nicholson, and Warren Beatty himself, it’s easy to forget how pervasively into the narrative are the film’s testimonials from real-life eyewitness. Far from just a framing device, the interviews often spill into the scripted sequences, effectively narrating and even motivating performance, mise-en-scène, and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro’s camera.

The film is similarly twinned—and blended—in terms of tone. The documentary footage starts off as sober if engaging testimony, while the John Reed (Beatty)—Louise Bryant (Keaton) story plays as a big screen romance, complete with witty repartee, irresolvable jealousies and passions, and old Hollywood charisma thanks to the rapid-fire elocution and self-effacing beauty of the leads. Beatty seems to have resolved to have his cake and eat it too, seriously relating the experiences of Yankee communists during the dawn of the Russian Revolution while entertainingly presenting a continent-spanning love affair for the ages. Yet just when it seems that tone will match form, the tenor of each shifts. A gossipy levity creeps into the talking head clips, while the fictionalized passages tilt into an invaluable dramatization of the ideological splintering of the Left—as it relates to the Reed-Bryant relationship, but also to the evolution of progressive political thought in the 20th century.

A final-act confrontation between Beatty’s Reed and Maureen Stapleton’s Emma Goldman—two Americans trapped in Moscow and by their own diverging ideologies—offers a commendably complex distillation of how philosophy is warped, inevitably if not necessarily, by the prospect of structural and political implementation. Reed comes off as a rational defender of the Soviet Union’s moral compromises, and Goldman as a stubborn dreamer absconding with the ugly complications of her beliefs, yet history tells us that for all of its ends-justify-the-means pragmatism, it’s the former that led to genocide.

Yet Beatty never gets hung up on foregrounding what would become of the Soviet experiment, and never demonizes those involved. Considering he was working within the Cold War, and specifically during a transition into Reaganite saber rattling, such restraint was either heroic or seditious, depending on one’s inclinations. In this respect, it’s the love affair that saves the film: we get to feel the urgency and weight of ideological convictions as they play out between two fully realized people whose passions are never condescended to, and never fully commensurate with each other. From Portland to New York to Provincetown to Moscow to a Finnish prison to the Middle East and back to Moscow, they pursue their beliefs and each other, which in the end seem both interchangeable and irreconcilable, and always worthwhile.

While Beatty’s leftist narrative is threaded together by romance, Philip Kaufman’s similarly sprawling adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s nonfiction novel The Right Stuff, released two years later, is ironically the one preoccupied by the notion of comradeship. Released the same year as Reagan’s so-called “Star Wars” defense initiative, it is a Cold War film about an earlier phase of the military industrial détente—the space race. Like Reds, Kaufman’s Oscar-winner conveys historical sweep via chronological progression, beginning with Chuck Yeager’s breaking of the sound barrier in 1947 and ending with Gordon Cooper’s orbital flight around the earth in 1963. What would seem like a straight-up stroke job for NASA turns out to be a far cooler affair, composer Bill Conti’s Wagnerian triumphalism notwithstanding. Such is Kaufman’s aversion to authority that every player who’s in a position of power or potential advantage—i.e., everyone who’s not either a test pilot or the wife of a test pilot—is subject to distrust and derision. This includes the head of the Mercury program (John P. Ryan), the NASA recruiters (Harry Shearer and Jeff Goldblum), Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson (Donald Moffat), the German-born physicists whose rockets and spacecrafts made space travel possible (Scott Beach et al), the press corps paparazzi (the Fratelli Bologna Comedia Dell’Arte group), assorted groupies and PR flacks, and even higher ranking military personnel.

But it’s not just authority that Kaufman distrusts—it’s the standard historical narrative. Thus, only air cowboy Yeager (Sam Shepard), by dint of his quiet courage and under-heralded contributions to evolution of manned flight, possesses heroism beyond question. By contrast, the Mercury 7 astronauts are introduced as an assortment of hot dog (Dennis Quaid’s Cooper), Dudley Do-Right (Ed Harris’s John Glenn), cut-up (Scott Glenn’s Alan Shepard), and fuck up (Fred Ward’s Gus Grissom), none of whom can hold a candle to Yeager, and none of whom appreciates the sacrifices made by their spouses. Their rise to heroism comes courtesy of a collectivist ethos worthy of John Reed—and foreign in the era of moral majority, small government, welfare-mother-baiting American individualism.

Though these sequences are set during the dawn of the Kennedy era, Kaufman clearly has more recent history on the mind when the astronauts begin to bicker about one another’s sexual indiscretions. Though both movie and family-values morality have trained us to side with John Glenn’s clean, though affronted conscience, it’s Alan Shepard, muscular arms folded against a thermal undershirt, who more persuasively throws down on behalf of sexual freedom and matrimonial complexity (notions that Louise Bryant echoes throughout Reds). Crucially, if a bit jarringly, it’s at this very moment that the astronauts shift from bickering boys to collaborating men. Grissom grunts that the real issue isn’t “pussy” but “monkey,” alluding to the fact that NASA intends to send a simian into space before them—this indignity (which would indeed come to pass) is enough to elicit a rallying cry of “we’ve got to stick together” and jumpstart Kaufman into the kind of mythmaking he can get behind. While Yeager exemplifies America’s unsung exceptionalism—a pilot’s pilot, a self-motivated warrior, a PR-allergic rough-rider—the Mercury 7 are variously ugly, or at least flawed Americans who form a more perfect union, one based on mutual respect, collaboration, and gallows humor. While Yeager remains on a pedestal—albeit one uniquely constructed of forgotten achievements and futile missions—Kaufman invites viewers to identify with the astronauts. We’re placed in the teensy space capsule to sweat out Glenn’s firey re-entry into the earth’s atmosphere, and to feel Shepard’s relief at emptying his bladder into his spacesuit. We’re also made privy to their shared language, with catchphrases like “Fuckin-A bubba,” “Everything is A-Ok,” and “Don’t screw the pooch” serving as refrains that, as if in a blues song, accumulate more meaning and emotion over time. It’s sloganeering, but from the bottom-up rather than from the top-down.

Of all the American cultural tropes at play in The Right Stuff—from Yeager the Western Hero to Shearer & Goldblum’s borscht-belt act—the most pervasive, and persuasive, might be that of the Frontiersman, staking out new territory on the borders of society (also explored, in a fashion, by bohemian utopianists Reed and Bryant in Reds). Bolstered by the support of his beleaguered family (Pamela Reed and Veronica Cartwright play homesteading spouses), hell-bent on confronting the unknown (personified here as a “demon in the sky”), and charged with forging new communities in the wild (both the virtual brotherhood of space and the rough, under-populated terrain of Edwards Air Force Base, California and Cape Canaveral, Florida), the frontiersman asserts his right to the land (space) by vanquishing his competitors as needed. On that last point, Kaufman replaces Native American rivals not with the Soviets, who are present only in briefly glanced newsreels and passing pejoratives (“Those dang Russians!” says Glenn), but with the parasitic, opportunistic military industrial complex itself. Victory isn’t in vanquishing this opponent, but in achieving goodness and greatness in spite of it.

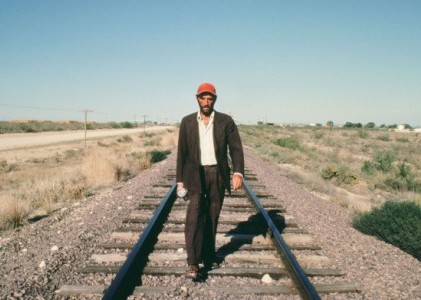

Though is hasn’t the historical sweep of these other films, Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas, released the following year, is no less preoccupied by the American mythos, and like Kaufman, by the myth of the American frontiersman in particular. It’s not hard to imagine Shepard’s Chuck Yeager drifting across the south Texas landscape of the film, and that’s not just because Shepard himself penned the story that director Wim Wenders and scriptwriter L. M. Kit Carson adapted into this feature. The film is both a deconstruction of and ode to the strong silent Western hero, here played by an amnesiac-cum-rehabilitated-cracker played by Harry Dean Stanton; and furthermore it’s both a valentine and jaundiced ode to the U.S. by Wenders, a West German raised, like much of Europe after the war, on American culture.

Whereas former Hollywood B-lister Ronald Reagan presented himself, in his presidency, as a square-jawed, A-list savior of American ambition, values, and provenance, Harry Dean Stanton’s performance in Paris, Texas serves as crucial counter-portrait of Yankee entitlement. He starts off as a man stolidly and self-indulgently driven to oblivion, and ends as a heartbroken man who’s wise enough to drive himself away from doing any further harm. He’s no longer dreaming heroic dreams, but rather working hard to repair what those dreams put asunder.

The frontier that Stanton’s Travis Henderson traverses isn’t for the sake of discovery, but recovery. Found literally wandering the desert, with no recollection of his own name, past or purpose, Travis just has the compulsion to walk headlong into the horizon. It’s a mad kind of romanticism, a coded American drive to just go, go, go, in which movement itself serves as purpose. But we eventually learn that, as with many if not most journeys, pushing forward is actually an attempt to escape from the past. The horizons that Travis pursues, and that DP Robby Müller breathtakingly captures throughout the film, offer not a solution but a salve. We’re used to seeing such shots—of train tracks in the desert, of Monument Park via helicopter, of the open road and L.A. highway overpasses, of windswept rest stops, of the subdivided valley as it meets the sky—as rich with poetic implication and metaphorical promise, but Wenders ultimately presents them as psychic dead ends. Doing so with the affection and studiousness of one whose aesthetics, if not ethos, is similarly compelled by such imagery (as he’d later prove with The End of Violence, his Edward Hopper fetish runs deep) only deepens the cut of his critique.

For Travis, redemption lies not in the unknown, but in remembering and atoning for what he’s desperately tried to forget. And what gets him there—the process by which he learns to properly provide for his son by reuniting him with his estranged wife—isn’t to do with vaguely profound Eastwood-esque eye-squints or quick-draw heroics, but confession. The two scenes in which Travis confronts his wife Jane (Nastassja Kinski) in a low-rent peepshow parlor, are among the most overwhelmingly, and exquisitely, cathartic in all of cinema, and not just because of Stanton and Kinski’s rubbed-raw monologuing. It’s also thanks to how we’re physically cornered by the truth, trapped in the tight quarters of the glassed-in booths (motel room- and American kitchen-themed to maximize greater cultural implications) after two hours of staring into the sky and out of windshields. Now it’s faces and words we’re fixed on, and there’s no way to either run from them or bring them any closer—a glass partition separates them, affording confession but precluding connection.

We’ve arrived at a reckoning for these wayward dreamers, onetime lovers who still long for each other but can no longer even safely meet each other’s gaze, and whose broken marriage suspends their young son in uncertainty. A million miles from the film’s opening shot of endless sky and desert, as well as from the promise of the road, we’re left only with flawed people and imperfect solutions. You could say this is the fallout from the American dream—passion perverted into a peepshow, hope dead-ended in divorce, loneliness, and desperation. But it’s also, in filmic terms, a triumph of the intimate truth over the ideological one, of the personal over the spectacular, of humanity over mythology. Though each of these three films has a grand scope and ambition, they’re defined by poignant interpersonal moments such as this one. In The Right Stuff, it’s when Gus and Betty Grissom explode in grief over his failed Mercury flight, only to lean back into each other, defeated but together. In Reds, it’s when a quivering Reed begs Jerzy Kosinski’s Zinoviev to be sent back to America from Moscow, insistent that he can be loyal to both the revolution and his wife—as well as in the regular, plausibly sloppy squabbles between Reed and Bryant that end in a separation that neither ever quite wants yet both somehow need. These may not be the sorts of scenes we think of when we think of 1980s cinema, or even the sorts of scenes that we recall about these widescreen epics, but to toy with President Reagan’s words again: to those who would say that it was a time when there were no non-blockbustered heroes—they just don't know where to look.

The Right Stuff, Paris, Texas, and Reds showed at Museum of the Moving Image as part of the series See It Big!: The American Epic.