Social Service

by Eric Hynes

Let It Rain

Dir. Agnes Jaoui, France, IFC Films

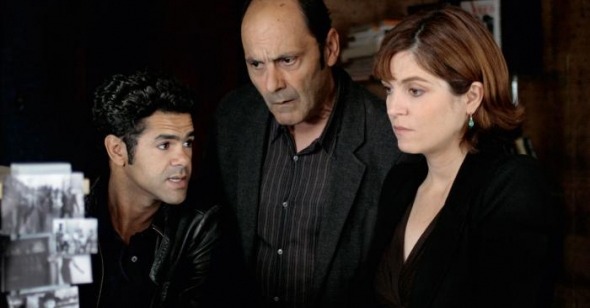

Agnès Jaoui’s Let It Rain begins with a sight gag worthy of Laurel and Hardy: a tall, balding Frenchman stands next to a short, thick-maned Algerian. The taller one, Michel (co-writer Jean-Pierre Bacri) offers his companion, Karim (Jamel Debbouze), a joint, which Karim declines. They start walking, Michel loping and lecturing, and Karim by turns hyperactive and self-conscious. Though a couple of decades younger, Karim’s the straight man to Michel’s slouching clown. Michel doesn’t think he’s a clown—and importantly neither does Karim—but his manner, all droopy eyes, furrowed brow, and mug mouth, tips off the audience. Michel recruits Karim to collaborate on a documentary, soaking up the younger man’s energy while disarming him with respect. From the outset they have an unlikely but pleasing rapport, setting a pattern in the film for various combinations of relationships—one more contrived than the next yet each, in the end, winning.

Navigating the rocky straits of the serious-minded comedy, Let It Rain maintains a breezy tone while hinting at deeper concerns. Such comedies are always tricky endeavors, as too much levity squanders efforts at gravitas, and self-importance stifles laughs. For every film that succeeds in mining comedy for serious Chekhovian pathos (Rules of the Game, Crimes and Misdemeanors), there are films like the contrived, schmaltzy Life is Beautiful, or the justly forgotten Mel Brooks goes homeless knee-slapper Life Stinks. On the whole Let It Rain manages just fine. If its balanced approach occasionally has the feel of compromise, of a middle course overly plotted to avert danger, the film nevertheless exudes a warm, world-weathered integrity.

Karim quietly bears the grudges of living as a non-white worker in an affluent holiday town in the south of France, where he manages a small hotel. When he approaches Agathe Villanova (Jaoui), a feminist politician he knows from his childhood, about serving as a subject for the documentary he’s making with Michel for a series on “Successful Women,” he’s polite but subtly disdainful of her. In turn, Agathe fiddles with her cell phone and studiously mishears him. Again, here are two people who’d seem to have no cause for interaction, let alone a shared past. Meanwhile a neurotic thirtysomething woman named Florence lives in a pastoral country house with her husband and children, complaining about the weather and worrying over the arrival of her sister: Agathe. Living next door is the family’s longtime housekeeper, Mimouna, who’s adored by Florence but condescended to by Florence’s husband, Stéphane (Guillaume de Tonquédec). Mimouna fawns over Florence and Agathe, thinking of them as grown surrogate daughters, baffling her own son—Karim—who thinks Mimouna has been mistreated and underappreciated by the family. To completely close the circuit, it’s revealed in broad, farcical strokes that hangdog Michel has been secretly carrying on an affair with Florence.

Which is hard to swallow. On first pass, the tidy cross-connections all feel false. Overdetermining Agathe’s self-obsession, Florence’s unhappiness, Mimouna’s sainthood, Karim’s anger, Michel’s haphazardness, each odd pairing threatens to play as psychosocial exercise. Watch Karim’s indignation toggle according to his companion, watch Agathe’s self-regard flip to self-hatred, watch Michel work harder to obscure his incompetence, and watch Florence run from and then retreat to her desperation. As conceived, the characters are too conveniently representational, too recognizable as role-playing types. Of course Jaoui’s project is to subvert expectations engendered by these types, to deepen and complicate shallow first impressions, but making the characters such quick reads allows for equally quick and easy complications, a passage that rewards and pleases audiences without really challenging them. Screenwriters Jaoui and Bacri have issues they want to explore through the characters, namely the politics of human relationships, and they show great attention to the slippage between what seems and what is. Racism, classism, sexism, victimhood: these all receive deliberate play within the confines of this extended family, which poses as a microcosm of France, Europe, western civilization, etc.

Saving Jaoui and Bacri from the schemata of their plot is their passion for the possibilities of dialogue. The contrivances of Let It Rain really do fade away whenever characters simply share a space and play around with words. Jaoui and Bacri excel at the minutiae of human expression, at the itty-bitty arcs of conversations, mining exchanges for moments of boldness, reckoning, and hilarity. Though never remotely plausible, Agathe’s consent to have hapless amateurs interview her over the course of several never-ending days does produce terrific duets each with Karim and Michel, while also providing the film with a pleasantly meandering through-line (as well as the film’s funniest set-piece—atop a rustic hill, a mass of barking sheep invade an ill-fated video shoot).

Though group scenes tend to spiral out of control a bit too readily, the duets have a welcome unpredictability. They come to life as pockets of fine theater. Which owes no small debt to Jaoui’s handling of an exceptional cast. There’s not a moment of actorly indulgence, not a scene in which one player overpowers or outshines another. Jaoui captures people in the process of articulating themselves—to themselves and others. Characters absorb and overtake pushy subtext, flashes of truth overshadow a tired interconnected plot, and Let It Rain ultimately succeeds by locating where humor and gravity overlap in the moments passed between people.