Open-and-Shut

By Elbert Ventura

The Lives of Others

Dir. Florian Henckel von Donnersmack, Germany, Sony Pictures Classics

An art-house hit in its first couple of weeks of release, the Academy Award-nominated The Lives of Others is a fitting coda to a movie year that was defined by the ascendant middlebrow. Like Guillermo Del Toro’s sham dazzler, Pan’s Labyrinth, The Lives of Others will draw the unadventurous cosmopolitan to the local Landmark chain—no doubt with the help of Anthony Lane, whose hilariously overwrought rave (“Es ist für uns”—uh, nein) displayed the kind of fervor that he reserves for books (and movies that most closely resemble them). Florian Henckel von Donnersmack’s debut feature is hardly a bad movie, but it can’t possibly bear the weight of the outsized praise heaped on it.

The lavish attention it received in its native Germany is certainly understandable. As what Allgemeine Zeitung called “the first film that puts the work of the Stasi [the East German Ministry of State Security] at the center of its plot,” The Lives of Others offers a novel dramatization of a European nightmare hitherto unexamined by the culture industry. By most accounts, the German reaction was something akin to therapeutic catharsis, and the film swept the German Academy Awards. But beyond its content and context, the movie is actually quite stingy with its gifts. Tasteful, effective, and complacent, it aims low and hits its mark.

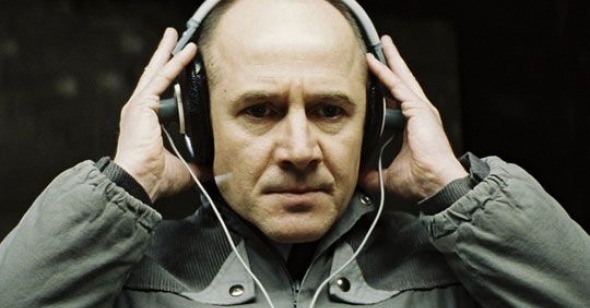

A schematic melodrama of moral awakening, The Lives of Others initially has the makings of a menacing Pakula-esque political thriller. We are in East Berlin, 1984, and the Stasi has found a new quarry—Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch), a playwright who becomes the target of a surveillance operation. Assigned to the case is Capt. Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühe), an exacting automaton of an agent—a model spook. But cracks in his socialist ideal begin to appear. Wielser finds out that the operation is motivated not by politics but sex: a party poobah wants Dreyman’s actress girlfriend, Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck), and will do anything to get him out of the way. Perched in the attic above Dreyman’s bugged apartment, Wiesler finds his sense of mission ebbing with each eavesdropped conversation. His creeping epiphany is matched by Georg’s, who finds himself increasingly disillusioned with the East German dream. Snooping gives way to surreptitious intervention, as Wiesler airbrushes Georg’s records even as the playwright edges toward dissidence.

The benevolent god to the Stasi’s malevolent one, Wiesler is a compelling creation. Recalling Gene Hackman’s Harry Caul in Coppola’s The Conversation, he’s a sad sack with no life. If writers are the “engineers of the soul,” as a party official says, Wiesler is its vampire. The movie’s neatest twist is to give its passive agent agency. The conversion from voyeur to savior isn’t entirely convincing, predicated as it is on Wiesler’s roused humanism—an awakening von Donnersmack sells to his audience with platitudes about the transformative power of art. But the director knows how to tighten the screws, and Wiesler’s tug-of-war between career and conscience supplies the movie its suspense, if not quite its power.

Partly out of its newness, partly out of skillful execution, the movie’s dramatization of life in a totalitarian regime is undeniably fascinating. When it turns its attention from contrived epiphanies and hairpin plot turns, The Lives of Others actually leaves you with something of what it must have felt like to live in the Soviet bloc. In one scene, a Stasi peon starts tells his colleagues a joke about the party chairman, not knowing that a supervisor is listening. The stunned look on his face deepens into horror when the supervisor asks him for his name, department and rank. But the stern superior suddenly bursts into laughter, and reassures the terrified employee that he was just joking—to which the hapless drone can only respond with a feeble smile. Who really knows? The Lives of Others does a creditable job of showing how paranoia becomes internalized, is essentially a state of nature, for a society living under Big Brother.

That paranoia infects even the most intimate relationships. The secrets that pile up between Georg and Christa arise from necessity; both understand that lies to themselves and each other are a vital part of surviving in a state where someone is always listening. But it’s an unsustainable condition, as the country’s high suicide rate implies. One of the movie’s cruelest ironies comes in a climactic interrogation scene between Wiesler and Christa-Maria. Forced by his suspicious boss to conduct the questioning of the arrested actress, Wiesler applies his vaunted methods and gets her to rat on Georg. The betrayal cuts them both deeply—Christa-Maria knowing that she may never look her man in the face again, Wiesler finding his faith in her goodness sabotaged by his own methods.

Much has been made of the movie’s politics, and deservedly so. Von Donnersmack’s movie is an explicit rejection of ostalgie, a strain of nostalgia for the simpler days of the GDR amid the confusing free-for-all of the post-unification era. A reminder of the horrors of the past, it is also redolent of the fears of the present. The movie suggests that perversity and caprice, more than anything else, underpin the authoritarian sensibility. The surveillance of Georg springs from the dirty mind of a horny functionary; his fate is essentially sealed when a party leader tells a Stasi agent: “There’s something fishy about this guy.”

Considering its shadowy subject, The Lives of Others is surprisingly bereft of mysteries. It is a movie that withholds nothing—its meaning is foregrounded, its form unsurprising. For all of the film’s championing of art, Donnersmack seems to hold little interest in his. What is von Donnersmack to cinema or cinema to him? The subject is so rich that the filmmaker’s literal-minded direction feels like a betrayal. With its dutiful cross-cutting and functional camerawork, the movie’s range of expression is woefully limited. Seemingly interested only in translating the words on the page into uncomplicated pictures, he shows no regard for using images to make or deepen meaning. Here’s a movie that takes voyeurism as its subject—and it doesn’t give a thought about its medium, the most voyeuristic of them all. In the hands of a Coppola, a De Palma, or a Hitchcock, voyeurism and surveillance become entry points into interrogations of subjectivity and explorations of the De Palma dictum: “Cinema is 24 lies per second.” Perhaps it’s unfair to assail a movie for what it didn’t do, let alone compare it to the work of giants, but the missed opportunities seem a symptom of a myopic vision.

And there are fewer graver sins in an artist than failure of imagination. Opting for melodrama and incident over reflection and nuance, The Lives of Others settles for banality when the raw material for greatness was there. Von Donnersmack makes a case for why his movie should exist, but left unanswered is why he makes movies at all. In a way, Wiesler is its perfect emblem, for the movie is as bereft of personality as its central cipher. Von Donnersmack’s failure to conceive of his ideas in cinematic terms isn’t fatal—there’s enough here to recommend it. (It may be uninspired, but it’s not inept.) But the fact that it has been hailed with near unanimous acclaim by the nation’s reviewers suggests that our benighted film culture may itself be in need of deprogramming to change its blinkered way of seeing.