Portland Tales

by Kristi Mitsuda

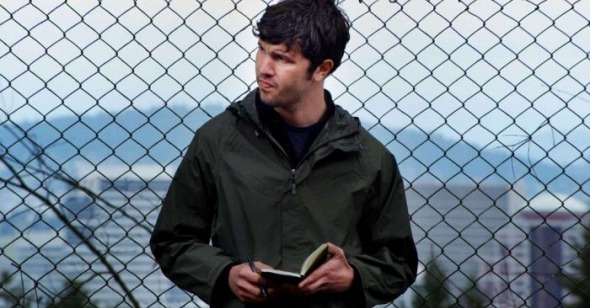

Cold Weather

Dir. Aaron Katz, U.S., IFC Films

The movement that doesn’t want to be known as “mumblecore” has been maligned for its focus on privileged, white twentysomethings (though to this charge, I’d argue that most American films focus on privileged, white something-or-others). Nevertheless, I’ve been quite taken by many of these modest proposals in the past (The Puffy Chair, Hannah Takes the Stairs, Mutual Appreciation, Humpday), encountering numerous moments of genuine recognition amidst its descriptions of awkwardness, aloofness, aloneness; which is to say, as something of a disclaimer, I don’t have a bone to pick with mumblecore, and I’ve found the level of vitriol directed at it by some critics outsized. Dance Party, USA and Quiet City established Aaron Katz as a member of the movement, and the latter film in particular distinguished itself from the pack by striving for an aesthetic appeal in a genre noted for being devoid of such concerns. Yet though Katz has a more developed eye, his ear and feel for naturalistic conversational rhythms—the bread and butter of mumblecore—are less so. Dance Party, USA was impressively assured for a first-time feature filmmaker, but Quiet City, though more visually eloquent, seemed to be inarticulate itself rather than an illustration of inarticulateness, a failing likely due in part to casting.

The same goes for Katz’s acclaimed new film, Cold Weather, which, as usual, takes as its locus a group of twentysomethings scrambling to define their relationships with one another, but then, in a gambit not dissimilar to Mark and Jay Duplass’s incorporation of horror notes into Baghead, the film segues into something more suspenseful. Cold Weather opens on an abstracted and slightly eerie image, still and focused on the raindrops flecking a window onto some unidentifiable scene, only pulled into clarity at the end of the credit sequence and revealed to be an ordinary courtyard of an apartment complex. This deftly manages to conjure an almost subconscious sense of foreboding, nicely foreshadowing the thriller turn the seemingly placid production will take. Although it contains a few more such sublime discrete moments, the following film in full doesn’t live up to the evocative elegance of this intro.

An expository family dinner establishes that Doug (Quiet City’s Chris Lankenau) has just dropped out of college in Chicago and returned to live in his hometown, later revealed to be Portland, Oregon. He’s renting an apartment with his sister, Gail (an uncomfortable-looking Trieste Kelly Dunne), and soon finds a job working the night shift at an ice factory, where he strikes up a friendship with Carlos, played by Raúl Castillo (an odd instance of ethnicity in mumblecore’s lily-white world). The two bond after the former reveals he was a forensic science major, which fascinates Carlos (“like CSI and shit?”), who ends up borrowing a Sherlock Holmes book from Doug. Doug’s ex-girlfriend, Rachel (Robyn Rikoon), enters the picture soon thereafter. Ostensibly, she’s in town because the Chicago law office where she works is based in Portland, and her company has sent her to the West Coast for training. She quickly becomes part of the gang, and it initially seems that the narrative might be driven by Carlos’s possible attraction to her, perceptible via his shy disavowals of interest to Doug (not to mention the fact that he accompanied her to her motel room after a Star Trek convention they attended together following Doug’s refusal of the extra ticket).

Characteristic mumblecore fumblings continue in this vein until, almost halfway through the film, the mood abruptly shifts from mellow to frantic, signaled by an overhead shot of Doug sleeping undisturbed on his couch as his cell phone blinks on the floor beneath him, followed by the jarring sound of the doorbell and Carlos rushing in. Carlos is agitated because Rachel didn’t show up to hear him deejay—his side gig—as she said she would; she also hasn’t answered her cell phone and isn’t answering knocks on her motel room door. Doug’s response mirrors our skepticism about this being cause for concern—after all, this is an era where flakiness in friendships is fairly common, given the myriad ways people can later excuse themselves via various technology: he doesn’t seem alarmed, but still allows himself to be taken to her motel so they can investigate. The door to her room is unlocked, and the room is empty. Doug continues to doubt that anything is amiss, until a nicely visualized moment when, just after proclaiming in frustration to Carlos, “There’s really nothing out of the ordinary in here, man,” he turns to gaze briefly out the window, his face blurred in the foreground; as a note subtly rises on the soundtrack (courtesy of Keegan DeWitt’s clever score), his face comes into focus and he turns to his friend and says, slowly and quietly, “There’s a guy in a pickup truck parked in the parking lot, and he’s watching us.”

It’s a truly creepy moment (Cold Weather nicely manages these on a few occasions), eliciting a shiver of fear that feels rooted not in some distant movie reality but in one you can imagine finding yourself; the movie certainly strives to walk this fine line between the everyday and the dramatic, but it only keeps its balance intermittently. From here on, Doug is committed to deciphering the mystery of Rachel’s disappearance, energized and suddenly filled with purpose, which is meant to be in contrast to his former slacker self. Curiously, although he had been so dogged in his pursuit, Carlos soon falls out of the picture (this is unfortunate, since Castillo has the most charisma of the bunch), presumably because he actually has to work for a living, though Doug seems to have no qualms about playing hooky—reinforcing the claim that mumblecore indulgently focuses only on characters seemingly immune to the monetary considerations that plague most of us. Narratively, this opens up a space for Gail to come in and play Nancy Drew to her brother’s Hardy Boy. [Spoiler] Upon the reappearance of Rachel, the plot takes another twist, as she confesses to Doug she’s been roped into a dangerous situation, of which she remains vague, but the gist is that she’s supposed to deliver a briefcase full of money, and it was stolen from her room. The new mission becomes to find the missing goods.

Despite all these twists, watching the duo move slowly from clue A to clue B isn’t particularly engrossing. We’re clearly meant to gather meaning not from the unraveling of the central mystery, but from Doug and Gail’s supposed reconnection with each other as siblings in the course of their sleuthing. Attention is directed along these lines since, during the amateur detectives’ downtime, Cold Weather focuses on trivial interactions between the pair—for instance, we’re cued to find it adorable that they go pipe shopping together so that Doug has something to smoke out of while he ponders clues, à la Sherlock Holmes—and the film concludes abruptly on a moment of triumph, which they share alone. But the brother-sister relationship never feels sufficiently organic or lived in for this to be enough of a payoff. From the beginning, it seems strained, and not in an intentional way; conjuring a vague sense of alienation between the two at first was probably the point, the better to later highlight growth, but the actors don’t create a believable dynamic. It’s not clear who’s older or younger, and the vibes between the pairing seem so off-kilter, in fact, that I initially wondered if Gail was Doug’s girlfriend—especially after she walks out of her bedroom early on in a Blazers t-shirt and sweats, serving as pajamas, and asks him if he’s coming to bed; this confusion is later compounded by her physical similarity to Rachel (both are dark-haired, sharp-featured and slim), a visual twinning apparently serving no end. Doug and Gail seem like strangers to one another at film’s start, and in the end, they still do; there’s no progression and, more than this, no undercurrent of familiarity, no inside silliness or ribbing in the usual fashion of siblings, no sense of a shared history.

And this is Cold Weather’s central failing; it seems to lack historical connection between characters or places in general, and there are no echoes to lend the story subtext, or layers that might move it beyond a staid telling into something more profound. None of the interactions between Doug and Rachel reveal anything in their past that might play off against the present situation to more prismatic effect. The only allusion we hear to their dating life comes up when Carlos mentions casually that he thinks Rachel likes baseball (in addition to Star Trek . . . what a catch!), because he saw a book of baseball statistics in her motel room; this surprises Doug, who claims she never liked baseball. But as it turns out this is merely a superficial clue strategically placed for the purposes of mystery solving to come.

If each of the characters is a tabula rasa, so is the setting. Katz envisions a Portland akin to a ghost town, barely peopled except in one scene where Doug goes to see Carlos deejay. Katz has even cleared nearby Multnomah Falls along the Columbia River Gorge, always thronged with tourists, for a scene restricted to only Doug and Rachel. Although this imparts a certain unnerving atmosphere, it also gives the city an inescapable blandness. And Doug leads a strangely hermetic existence— given that Portland is supposed to be his hometown, it seems odd and overdetermined that his circle includes only his sister, a guy he just met at work, and his ex from another city. His parents make a brief appearance at the start of the film and apparently live in town as well, but they’re never seen or heard from again. At one point during a stakeout, he asks Gail whether she has any friends—since he hasn’t seen her with any—but you wonder the same about him. Doesn’t he have any childhood or high school friends left in the area?

On paper, a high-concept mystery mobilized as a vehicle to bring brother and sister close together again after years of geographical separation sounds like a lovely idea. Perhaps if Lankenau and Dunne had been given direction regarding actorly business or body language—which might’ve helped flesh out the minimal and not particularly illuminating, often facile, dialogue (upon being directed by Doug on how to navigate an adult website in search of a clue, for instance, Gail says “You seem pretty familiar with how this kinda site works”), the relationship might’ve felt more real. As it stands, the movie seems to mumble a bit, but lacks, well, a core. And, in terms of the detective angle, the finale leaves one with more questions than answers. I found myself trying to fill in the blanks (and perhaps invented some possibilities) simply to entertain myself as the movie meandered on: Did someone really steal the suitcase from Rachel, or is she stealing it? Are Rachel and Carlos perhaps in cahoots? Ultimately, though, I sadly realized I didn’t care.