All Fall Down

by Jeff Reichert

Collapse

Dir. Chris Smith, U.S., Cinetic

At the turns of decades and centuries, it’s fairly common for sky-is-falling prognostication to spike wildly. This angst often finds expression in popular entertainments, such as the appearance, as if on cue, of the clunky misfire Knowing and the upcoming sure-to-be tedious 2012. What these kinds of spectacles provide is something like diversionary exorcism—the world outside may seem bad, but there’s some comfort in recognizing that visual effects artists can always imagine even worse. These films are about as easy to dismiss as History Channel specials on Nostradamus, and probably less fun, so Chris Smith’s often unnerving documentary Collapse arrives as something of a minor key paranoiac balm. Based on real events and plausible conjectures, its world crisis feels terribly immediate.

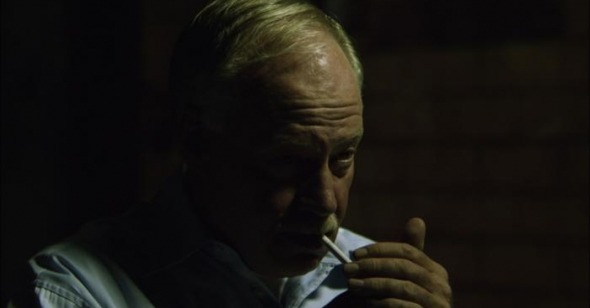

Michael C. Ruppert, an ex-LAPD officer with a shady, half-sketched past involving assassination attempts and run-ins with the CIA, arrives onscreen bursting at the seams to share the long-gestating grand unified theory of impending global meltdown he’s been peddling in lectures, newsletters, and blogs for years. He’s an unlikely prophet, and Smith’s already announced the unlikeliness of Collapse itself via title cards: in the process of researching for a script about the drug wars, the filmmaker turned up the unknown Ruppert, a man who the text describes as having “other things on his mind,” and decided there was a film to be made. Ruppert, bald, mustachioed, gruff, chain-smoking, and forcefully eloquent, pays immediate dividends as a documentary subject by cleanly and ably linking the warnings of the peak oil and sustainability movements to the nefarious politicking of recent wars and bailouts. He singlehandedly distills the lessons of films like American Casino, Crude Awakening, and Food, Inc, as well as any number of Bush-era war docs into a coherent systemic vision — and this alone answers the film’s opening question. What filmmaker wouldn’t want to make a movie about this guy?

When Smith asks his subject about criticisms of his theories (we never see the filmmaker, but his questions often serve as aural punctuation to his subject’s rants), Ruppert retorts that his ideas, which point inexorably towards the end of industrialized society, are “conspiracy facts.” Smith plays with belief throughout Collapse, never going so far as to undermine Ruppert, but never fully endorsing him either, accomplishing this careful straddling via smart structuring and careful inclusions that reveal Michael’s character simultaneous to the unspooling of his ideas. Over the course of Collapse, Smith even coaxes a cockeyed, emotional optimism from Mr. Grim, bringing him to tears in the face of the positive possibilities collapse opens up for humanity. It’s the literal end of the world, but only as we know it. From dire start to hopeful finish, Collapse certainly features quite the arc.

Smith sets Ruppert in what seems like an underground bunker and lets his cameras carom around his subject, offering multiple angles which are jump cut amongst very simple b-roll (typewritten chapter headings, reshot television monitors) and straightforward archival footage. Collapse is nothing if not aesthetically elegant, but given that Ruppert cries throughout the film for a paradigm shift in human living, one might wish at points for something similar in the filmmaking. Smith, a smart filmmaker who’s jumped across a variety of modes in his career, has skewed towards the cooly Errol Morris-like in Collapse (even down to a Phillip Glass-aping score). This formal elegance initially reads as a far cry from his previous, more ramshackle investigations of Americana, but this purposeful appropriation is less some kind of production solution or copycatting than a sly way to manipulate our expectations.

Over the course of a little more than a decade, Smith’s turned out a mixture of documentaries and features that often seem dissimilar on the page but link up in unexpected ways: American Job, American Movie, and Home Movie might seem like an insular trilogy (even if his first film is documentary in style only), but Job resonated throughout the very different working-class of his India-set The Pool, while many of the globalization jitters expressed via pranks and humor in The Yes Men end up reiterated darkly in Collapse. By the end of his new film, as Smith has ably positioned Ruppert so that our belief in his prophecies is much less important than our fascination with his belief in them, Collapse has revealed itself as very Smith-ian indeed. Ruppert in the end, for all of his talk and intelligence (and all the credence Smith’s filmmaking lends him at the start), is just another striver and dreamer—a Mark Borchardt struggling to make the world into a place where the Yes Men wouldn’t be necessary. It’s certainly possible to overstate the case for auteurism, to look to hard at a body of work and make links that aren’t there, but Smith’s career, for all its variety, feels surprisingly whole. It’s been a pleasure to watch this career evolve into one of the more fascinating in American independent film.

This article originally appeared on indieWIRE.com.