To Be or Not to Be

by Michael Koresky

Weekend

Dir. Andrew Haigh, U.K., IFC Films/Sundance Selects

After seeing Andrew Haigh’s Weekend for the first time, my boyfriend and I got into a debate. This is appropriate enough following a film that centers on the lively and sometimes contentious discussions between two young men. Our talk was about whether this brand-new movie—which charts the blossoming romance between two young men as they get to know each other over the course of a few days after a casual hook-up—felt dated. Did its poignantly dramatized questions regarding sexuality remain relevant in this allegedly “post-gay” world? Was it the kind of stridently queer film that could have just as easily been made and released to an appreciative niche audience in 1989, 1994, 2001, or today? Moreover, did that matter, and what does it mean for a gay film to speak to a gay audience in 2011? We finally realized, and mostly agreed, that the issues (if that’s the right word) that Weekend raises around homosexual identification, both externally and internally, remain largely unchanged in the past few decades, regardless of any political strides made. This is because the political is most certainly personal in Weekend, which speaks eloquently to today’s experience with an intimacy that transcends era.

Moreover, as a specifically British film, it speaks to a particular experience of difference in the new Europe. Its protagonist, Russell (Tom Cullen) and his bar pickup, Glen (Chris New), live in an evidently working-class suburb of Nottingham, marked by low-rent high rises and drab public spaces of sparse grass and abundant concrete. The plot is profoundly simple and seemingly uneventful yet is all forward motion: sweet and shy Russell, on his way back from a Friday night get-together at his straight buddy’s home, stops off at a gay pub, and after some light cruising, ends up awaking in his bed the following morning next to brash artist Glen. Initially, Glen makes Russell feel like little more than just another roll in the hay, as he takes out a tape recorder so that Russell can verbally recap the details of their encounter, an addition to an ongoing art project. But eventually, over the course of Saturday and Sunday, the two realize they have feelings for one another that go beyond sexual attraction—this despite Russell’s reticence to be out and proud with his emotions and Glen’s staunchly individual stance that having a steady relationship would be reflective of society’s alleged hetero-normatizing of homosexuality.

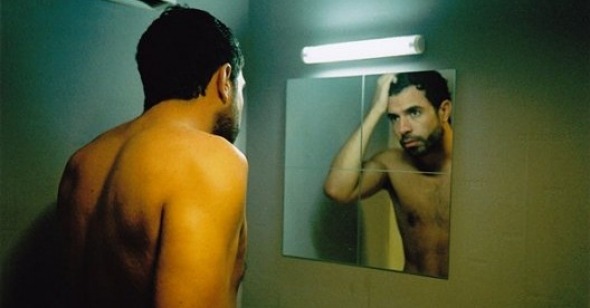

Thus, Russell and Glen come across as symbolic, each representative of a type of contemporary gay man—the gentle semi-closet case (not out to coworkers) desperate for love and the militant, antiestablishment guy terrified of labels—though they are also both remarkably specific. This is thanks to a combination of Haigh’s laser-sharp writing, directing, and editing, and the tactile, lived-in performances of New and especially Cullen, who constantly seem to be shedding their skins little by little over the film’s fleet ninety minutes. And speaking of skin, the film doesn’t shy away from bodies, working from the outside in: at the beginning we get an image of Cullen bathing in the tub, preparing for his Friday night; his body is hairy, excitingly real, and we get a glimpse of cock through the suds. It’s less sexy than matter of fact, a statement of intent—not only that Haigh will refuse to shy away from male nudity but also that his characters’ disrobing will not be a focal point, a climax for viewers to anticipate. In other words, for all its explicitness, Weekend is defiantly nonpornographic, even going so far as to deny viewers the pleasure of Russell and Glen’s anonymous first sexual encounter. Haigh’s handling of this is deft: after scoping out the smoky, pulsating club for a bit, Russell catches Glen’s eye, an exchange of glances that Haigh shows to us in the bar’s mirror. The two men play further rituals of seduction at the urinal, as Glen, clearly interested, teasingly walks away from Russell. In the next shot, Russell is canoodling with a markedly less attractive guy, and Glen is reclined on a couch in the far back right of the shot, watching. Cut to the next morning, and Russell, rumpled in a black t-shirt and tighty whities, is making coffee for Glen, who’s sprawled out in briefs across a much-used bed.

The specifics of their hook-up only come to us through Russell’s tentative narration for Glen’s art project, which he grudgingly agrees to. The camera stays trained on Cullen throughout the scene, as he grows increasingly comfortable detailing the night before. With Glen’s egging on, what we get is far more vivid than we could have had with a strictly visual representation, an erotic cataloguing of the ins and outs of gay sex rather than a disconnected random sampling of images: Glen licking Russell’s armpits, the sensual removing of shirts, concerns about sweat and smells, playing with assholes, the decision not to fuck. Most memorable is Russell’s bemused recollection of Glen kissing his neck and his—long pause as Cullen points downward—hand, an unexpected sweetness for both him and us.

It’s all a reminder of the power of words—an efficient prologue to a film loaded with intense verbal exchanges. Weekend will feature two more sex scenes, and they will grow increasingly graphic: Haigh only seems interested in showing their erotic encounters the more emotionally meaningful they become. It’s a distinct philosophical choice that stands apart from the film’s generally discursive tone, which takes into account both Russell’s romanticism and Glen’s aggressiveness. It’s in this regard—Haigh’s overall refusal to side completely with either of his main characters in their antithetical pursuits—that Weekend most distinguishes itself. The film plays as an ongoing pas de deux that’s a meeting of the minds as much as the flesh.

Just before Glen leaves Russell’s shabby high-rise apartment, they enter each other’s numbers on their phones. From the fourteenth floor, Russell watches Glen trudge off through the courtyard, a speck in a yellow hooded sweatshirt (it’s an image that will recur twice more, and, like the sex scenes, will gain in emotional resonance each time). As he walks away, we faintly hear some bully yelling “queer!,” the first of many reminders that the love we see unfolding naturally onscreen is hardly an acceptable part of mainstream culture. It’s a reality that incites Glen’s confrontational nature, which manifests not only in his art (wanting to regale straight audiences with the realities of gay sex, which even gay men feel too ashamed to discuss in public) but also in his social life. Later, during a party at a mixed bar, he takes a burly dude to task who had complained that Glen’s group was too loud, insisting it was homophobia that drove the man to try and quiet them down. Russell would rather not get involved, as it’s clear from scenes of his Saturday morning stint at the pool where he works as a lifeguard—his piggish hetero coworkers regaling each other with stories of “fucking pussy” as Russell sits quietly, uncomfortably nearby.

As evidenced in his first feature, 2009’s Greek Pete, a penetrating docudrama about a British rent boy, Haigh has an innate talent for knowing where to put the camera to capture the beauties and anxieties surrounding sex; Weekend takes it further, using sex as a springboard for a study of grace under social pressure. It’s practically brimming with moments of clarity that only a deft observer of human nature could summon. Among its many little joys are Russell deciding whether to end a day-after text message to Glen of “I feel like shit” with an “xo,” a smiley face, or no punctuation; fleeting shots of Russell struggling with whether to wear his old shabby pair of sneakers or the new ones still in the box; the way Glen sensually, amusingly munches a candy bar when listening to the story of Russell’s life, practically licking his lips when he finds out that he was an orphan; a tentative kiss on the way out the door following their second sexual encounter (the first had been a solemn handshake); Russell wiping a small puddle of ejaculate off of his tummy. Haigh is extraordinary at pinpointing those textured moments that make us nod and perhaps wince in recognition. If Weekend felt at all like a treatise on the State of Being Gay Now the easygoing charm that makes it so special would have been obscured.

At the same time, the film is uncommonly eloquent with the tenor of the discussions around homosexuality circa 2011. By design, Weekend is hardly the gay marriage film we’ve all been waiting for, but it’s engaged in a fruitful debate reflective of the subject nevertheless. Glen believes that gay people don’t need to be married to be considered respectable, that it’s a sign of giving into the “system”; Russell feels that for a man to stand up and declare his love for another man is itself a radical statement. Weekend is not as interested in being subversive as in asking what counts as subversive today. Russell and Glen are not on opposite sides of a debate as much as they are kindred forces able to challenge one another’s preconceptions, to make the other examine himself—in other words, they have the makings of an ideal couple. If Weekend ends up idealizing that couple perhaps a bit too much (the climax of the film gets slightly bogged down in last-minute-goodbye sentimentality, which puts it a little too firmly on Russell’s side), it still always manages to avoid making Russell and Glen feel like a manufactured movie couple. Tom Cullen is so authentic in his rugged shyness, and Chris New’s impish, ever-so-shaky self-confidence is so vivid, that Haigh’s film feels genuinely voyeuristic as it peels their layers away. It’s a film so emotionally in the moment that it gives the lie to the term “post-gay.”