A Talking Picture

By Andrew Chan

Fengming: A Chinese Memoir

Dir. Wang Bing, China

Night is falling as an elderly Chinese woman sits down in her armchair, faces the camera, and begins recounting her life story. In the Fifties, He Fengming was a journalist who had turned down a promising academic career to become a revolutionary. At the height of Mao’s Hundred Flowers Campaign, during which intellectuals were advised to contribute their opinions and let “a hundred schools of thought contend,” her husband wrote an essay criticizing the corruption of bureaucracy, which led to the couple being branded as rightists. A long period of darkness ensued, separating the family, and transporting the woman from one state of persecution to another in China’s labor camp system.

As Wang Bing’s documentary Fengming: A Chinese Memoir captures the woman’s confession over the course of three hours, night soldiers on until we can barely see her face in the shadows. The camera, a still and patient witness, never averts its gaze, even when she gets up to use the bathroom, or receive a phone call, or turn on the apartment’s harsh fluorescent lights. Shot in murky DV, this is a film that accepts the banal cycles of everyday existence, as if to save the “atrocity genre” from its own vulgar clichés. What emerges is a consummate work of art in the guise of a bare-bones oral history, as well as a remarkable piece of nonfiction that makes the whole art vs. non-art question seem beside the point.

Fengming is hardly the most charismatic, sympathetic, or even dramatic of film subjects. Her contribution is straightforward; she foregrounds the story and minimizes personality. Her hands never leave her lap, and her voice, roughened by age, maintains a uniform pitch and volume, except during the few occasions when she chokes up. While there is rarely a moment when her testimony sounds scripted, most of what she shares has likely already been rehearsed in her book My Life in 1957 (unfortunately not available in an English translation)—the kind of indictment of the Communist regime that’s regularly banned in China. Both filmmaker and audience are placed directly opposite her, in the uncomfortable position of watching her expose old wounds for our examination, but Fengming herself never seems surprised by the emotions she dredges up; her speech moves with the smooth progression one would expect from a narrative that has been previously constructed for the page.

No matter how Wang’s static frame seems to dare (or beg) the interviewee to break down on camera, the film never hinges on crude, TV-journalism revelation. What keeps Fengming consistently riveting, beyond the sometimes unbearable details of its central monologue, is the interplay between minimal emotional expression and the layers of irresolvable anguish that occasionally rise to the surface. This is not a film about reflection, since stopping and actively engaging with these memories might mean falling apart. Nor is it about a woman who has made peace with past injustices. Rage and bitterness—always directed toward groups and institutions rather than any identified individuals—live on, and are clearly reasons behind her participation in this documentary, even if they appear only in brief flickers across her face.

Those who follow contemporary Chinese cinema may know Wang Bing as an auteur to rival Jia Zhangke in ambition, tirelessness, and hyper-relevance. His only previous feature film is 2003’s unwieldy three-part, nine-hour Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks, a chronicle of a disappearing industrial district in Shenyang. This debut, which never found much of a home outside of festivals, contains extraordinary images in which the physical presence of the camera becomes a poetic device: for example, a shot taken from the front of a moving train as snow gently gathers on the lens; and another scene in which the camera itself seems to be shivering and breathing heavily as we trail a man on a cold winter night. Whole hours must consist of human figures being filmed from behind as they walk through harsh terrain in haunted, Béla Tarr fashion—as if the filmmaker were constantly posing the questions: Where are they headed? And how does a person, or a society, move forward? It’s the kind of achievement that leaves a viewer stunned and drained. Still, I found myself wishing Wang had offered more than a mere handful of memorable characters along the way—a surprising wish, since he follows his subjects so closely that we can’t help but indulge in the illusion that we’re participating in their lives.

Fengming begins like an extension of Tie Xi Qu’s style. We linger a few steps behind the woman on her way home, alert to the slowness of her movements, hearing the swish of her pant legs above the neighborhood noise. But, not unlike Jia’s recent 24 City, the film reveals itself as an experience of language rather than action. We are not asked to walk a while in a character’s shoes or see through a character’s eyes, as we were in Wang’s debut; here, we are asked to simply listen. Both director and audience occupy the position of guests. The result is powerful and ethical, a combination of a soul-baring premise with a filmmaker’s respect for his subject’s emotional privacy. It’s an indication of this respectfulness that, as Fengming walks into her apartment in the opening shot, Wang hesitates at the threshold, and upon entering maintains such a polite distance that it’s impossible to ever know if the woman’s eyes are filling with tears.

Over the past decade, mainland Chinese directors have offered fictional portraits of the nation’s modern malaise in a variety of flavors, ranging from the long-take asceticism of Jia’s Platform and Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide, to recent gut-wrenching melodramas such as Summer Palace and Blind Mountain. Often, the characters in these films are not endowed with a distinctive subjectivity, but are depicted as being swept along helplessly by the currents of change. Fengming paves a new path by looking back, evoking traditions that shaped Chinese subjectivity in the last half century. It’s tempting to read the film as a persecuted bourgeois intellectual’s reclamation of suku, the Communist practice that encouraged peasants to exercise political agency by airing their grievances in public.

One could also consider the film a revision of the “talking heads” style that revolutionized Chinese documentaries in the early Nineties (particularly in the groundbreaking films of Wu Wenguang), advancing the form beyond scripted lectures and newsreels. As Bérénice Reynaud has noted, these interview-based films succeeded in “‘giving the floor’ to people whose voices had never been heard before.” Fengming is such an extreme, envelope-pushing appropriation of this confessional mode that Wang has even forgone the use of interview questions, handing his subject almost complete authority over the shape and content of her storytelling.

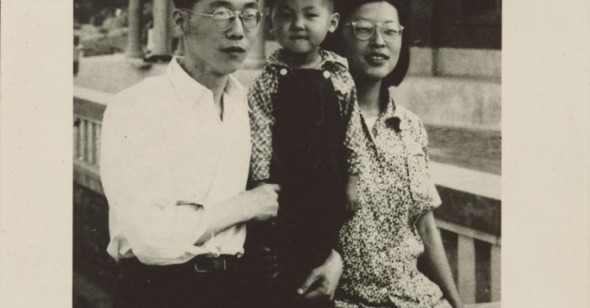

While Fengming’s achievement must be appreciated as culturally specific, it is at the same time philosophical kin to Claude Lanzmann’s Holocaust documentaries, in which the weight of historical atrocity is felt through a stern refusal to visually represent the past. Not only is there no footage of Communist “struggle sessions” or labor camps included in Wang’s film, but we also never see old photographs of Fengming and her family. Where a Fifth Generation masterpiece like The Blue Kite imagined the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution in vividly dramatic terms, Wang acknowledges the generation gap separating himself from those events. In his own confrontation with that preceding era, history is forced to speak through absence and distance, to reassert itself in what the living have left to offer us.

The American poet Muriel Rukeyser asked, “What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?”; her answer: “The world would split open.” The tragic extremes of Fengming’s biography seem to demand such a cosmic response, or at least some physical manifestation or visual correlative onscreen, and yet that’s precisely what Wang denies us with his stable camera and minimal editing. Spoken in a small voice in the privacy of a woman’s cramped living room, truth is stripped of its melodramatic and heroic trappings—self-evident in its value, but uncertain in its efficacy as a catalyst of social (let alone supernatural) transformation. Above all, in the span of these three hours, we experience Fengming’s safety—her freedom from physical harm and the fear of greater loss—as if it were as epic a condition as political peril. We wonder how a life that has been propelled moment-to-moment by struggle adjusts to this sedate, solitary aftermath, on this side of a horrific century. Teacups sit on a cluttered table; a microwave is perched on a stand in the corner; a poster of the character fu—meaning good fortune—lies inconspicuously and without irony on the sofa. And light through a window may or may not signal the persistence of beauty. The unshakable power of Wang’s film lies in the tension between its fraught subject and its calm setting, in its desire to function as both a cry of pain and a sigh of relief.