Strained Seriousness

By Adam Nayman

The Dark Knight

Directed by Christopher Nolan, U.S., Warner Bros.

A catch-22: Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight demands, in a mean, raspy voice, to be taken more seriously than your average comic book movie. But when one endeavors to do just that—to analyze its loudly explicated themes of duality and ethical impasse; to parse the implications of having its villain be referred to and self-identify as a “terrorist;” to consider the use of invasive surveillance technology as a post–Patriot Act plot point—one is reprimanded for bullying a defenseless Pop object. Hey, guys, why so serious?

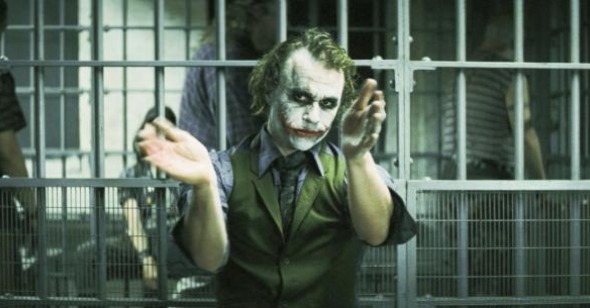

It’s a frustrating double standard, and while it shouldn’t preclude an examination of what’s wrong with The Dark Knight, it does give a critic pause—and so does the astounding volume of angry correspondence generated by the film’s fans on message boards and website comment threads. Those critics who didn’t see fit to acclaim the film a masterpiece, or at least a genre high water mark, find themselves perched precariously above an angry horde calling for their heads (or worse), much like —SPOILER ALERT! —Batman at the end of The Dark Knight. For the eight people reading this who didn’t see the film on its record-breaking opening weekend, the film’s final moments find Batman manfully taking the rap for the crimes of the deceased Two-Face/Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart) so as to make the latter a martyr for good in the eyes of a populace reeling from the brutal crimes perpetrated by the Joker (Heath Ledger).

It’s arguable that Gotham City is the real protagonist of The Dark Knight, and that the aforementioned trio function as a kind of externalized psychic apparatus, with Batman as the ego, the Joker as a mad-dog id, and Dent as a brutally bisected super-ego. If that sounds insufferably pretentious, it’s in line with the general tone of the film, which is heavy on psychologizing but light on actual, plausible psychology. It’s obvious, for instance, that Nolan and his co-writer (brother Jonathan) have read Alan Moore and Brian Bolland’s landmark 1988 graphic novel The Killing Joke, widely acclaimed for its lacerating take on the Joker/Batman relationship, and apparently presented to Heath Ledger before shooting for reference purposes. This correspondence surely helps to account for the impressively demented bent of Ledger’s performance, which is easily the least comic screen take on the role to date, but it also points to why this incarnation of the character is so unsatisfying: The Dark Knight gives us the vicious, intractable Joker of The Killing Joke without any of Moore’s carefully prepared backstory.

In fact, the filmmakers make this elision a point of pride: it’s a running gag in the film that the Joker likes to confuse the origin of his facial scars. He does the same thing in The Killing Joke (“if I'm going to have a past, I prefer it to be multiple choice!”), but even if Moore intends his star to be an unreliable narrator, the details of his past—a stifled stint as a stand-up comedian, exploitation at the hands of criminals, the tragic, accidental deaths of his wife and child—imbue his subsequent descent into insanity with some dimension.

Perhaps fearful of burdening their film with too much exposition (an oft-cited flaw of Batman Begins), the Nolans take a shortcut, presenting a prefab psychopath whose lack of a conventional criminal agenda allows them—and acquiescent critics—to make bold allusions to a terrorist ethos. Except that the last time I checked, the issue with jihadists was not that zey believe in nossing, Lebowski; equating the Joker’s pseudo-Nietzchean ramblings about the fragility of the social order with real-world terrorism is at best specious and at worst offensive. The film’s stance on surveillance technology is similarly problematic. While I won’t venture into Dave Kehr territory by suggesting that Nolan is endorsing warrantless wiretapping, there is something disconcertingly easy about the way that particular plot strand gets knotted: Batman rigs his all-seeing TV Eye to self-destruct once its purpose has been served. A neat trick, but also pretty easy, ideologically speaking.

Actually, a lot of The Dark Knight is easy. The Joker blows up hospitals but not before we’ve been reminded (several times over) that the structures have been evacuated; he sticks pencils into the eyes of criminal confederates (at which point Nolan’s camera cuts away so as to maintain the sort of rating that allows for the breaking of box-office records); he crows that he’s blackened the soul of an entire city when the people we’ve seen die are, with one exception, mostly low-level thugs and crooked cops. As for that one exception—SPOILER ALERT TWO!—while it may be gutsy for Nolan to pin The Dark Knight’s emotional heft on the murder of perky D.A. Rachel Dawes (Maggie Gyllenhaal, unflatteringly photographed and doing a half-decent Katie Holmes impression), it’s also unsuccessful. Rachel’s “tragic” relationship with Harvey Dent—conveyed through a series of utterly conventional dialogue scenes in which love is bandied about but never expressed through performance—seems like a device, another shortcut, an easy sacrifice.

And it doesn’t jive with the roots of the Two-Face character, either. In lieu of giving us a Joker created by Batman (a scenario looped all the way around in Burton’s film), we get a Two-Face created by the Joker, a sly bit of rewriting that allows for the film’s best scene—in which Ledger successfully holds our attention while acting against Eckhart’s phenomenal, CG-assisted makeup—but also doesn’t lead to much of a payoff. For the purposes of convenience, the film manufactures antipathy between tarnished white knight Dent and ever-decent Commissioner Jim Gordon (Gary Oldman), with Batman reduced to cameo duty in their final standoff.

This showdown is rendered even more perfunctory by being placed after an extended sequence in which the Joker, who has spoken at length about his dislike for planning, lays out a complicated scheme in which two ferryboats are rigged with explosives. The passengers on each boat have been charged to blow up the other vessel (one of which is populated almost entirely by convicts) in order to save themselves. This is supposed to be the gesture that breaks Gotham’s brain, that proves that its citizens are capable of anything once they’ve been pushed to the edge. Onscreen, there’s much hand-wringing about just how close these ordinary people come to committing murder—each boat holds a vote, and there are lots of shouted lines along the lines of “it’s them or us”—but those of us in the audience who are not entirely impressionable know that there is no way, in a $150 million dollar franchise film that a ferry’s worth of bystanders are going to be blown up. (Maybe if Tony Scott had directed it.) So we just wait out the inevitable revelation that the Gothamites are inherently decent folk above such provocations—and, of course, the biggest, scariest, blackest of the convicts is the one who throws the detonator away, after making like he was going to push it. What a twist! And how insulting, both that Nolan would try the old reverse-racism trick in the first place, or that he expects anybody to feel chastened by this feeble little feint.

That The Dark Knight is perfectly well-made by the standards of movies in its budget range is not exactly a compliment: should we expect less from talented people working with basically unlimited resources? And it’s certainly not much more than well-made. For every nicely executed image—a semi-truck flipping over in the middle of a city street; the Joker doing his best golden retriever impression out the window of a police car; a beautifully shadowed Dent giving us his “good” side while excoriating Gordon; Ledger’s final monologue, in which the Joker’s topsy-turvy worldview is given obvious but still eloquent visual expression—there’s a botched sequence (the opening bank job only superficially suggests Michael Mann, who understands how to delineate space and cut on movement), a ragged transition (a bit where Batman/Bruce Wayne leaves the balls-out insane Joker alone with a roomful of helpless party guests is gracelessly handled), or a wasted major actor. Neither Freeman nor Caine, both of whom were peripheral highlights of Batman Begins, have much to do. Nor, for that matter, does Bale, who essentially cedes the movie to Ledger and the wittily cast (and perfectly game) Eckhart.

Reviewing Guillermo Del Toro’s Hellboy II in Reverse Shot, a colleague wrote that “what’s most obscene about this pop-cultural mythmaking is that it works so resolutely against expanding taste or knowledge about movies. By focusing so obsessively and voluminously on the most readily, tyrannically available items, critical discussion is not simply reflecting the commercial film distribution situation in North America, but actively contributing to it.” On this note, I’m not sure that I can really divorce my sincere disappointment with The Dark Knight (and I was disappointed; check my three-year-old Batman Begins review for my optimistic guess about the series’ direction) from my irritation with its critical reception: a veritable ticker-tape parade, with enough bullies lining the route to shout down even the more nuanced voices of dissent. That a lot of viewers honestly like and love this flawed and overrated movie is fair enough, but the endless superlatives being hurled by critics high and low help to make perspective—a rare commodity—a casualty of hype. And whereas resurrection is a regular occurrence in the comic-book universe, in reality, what’s dead stays dead. Maybe we need to take The Dark Knight seriously after all.