Ford the Stream

by Jeff Reichert

Crossing Over

Dir. Wayne Kramer, U.S., The Weinstein Company

You’ve probably looked away from the poster for Crossing Over any number of times—the ghastliness of the monochromatic, pupil-less Harrison Ford at its top is matched in fright factor only by the paunchy, lipless Ray Liotta cut-out staring over at Ford full of longing (to round it out, Ashley Judd and Jim Sturgess seem to cringe off into the background). Forget entirely the noxious, nonsensical tagline (“Every day, thousands of people illegally cross our borders . . . only one thing stands in their way. America.” Huh?) and the poor stab at deconstructing the American flag into ribbons of red and white freeways—this thing screams “tossed-off” to its very core. It’s nice when a piece of marketing material inadvertently reveals the truth of the product at hand; given the law of averages, it was only a matter of time before a film came along that managed to out-stupid Crash, and, now we have it.

Immigration policy, ever a divisive issue, went almost completely undiscussed in our recent election, so we should be thankful that Wayne Kramer, creator of such socially conscious fare as The Cooler and Running Scared, decided to bring his prodigious talents to bear on this national blight. Taking as his apparent inspiration eighth-grade essay-writing lessons and Paul Haggis’s Oscar-winning masterwork, Kramer has managed to spin an intricate web of ethnic stereotypes who, in lieu of dialogue, all spout a collection of simplistic topic sentences that left my reserved press screening audience squealing with laughter. An immigrant himself (from South Africa), Kramer’s written, directed, and produced this thing, so he owns it. The large ensemble cast (including also Alice Braga, Cliff Curtis, and Towelhead’s poor Summer Bishil) is simply taken for the ride, and it shows.

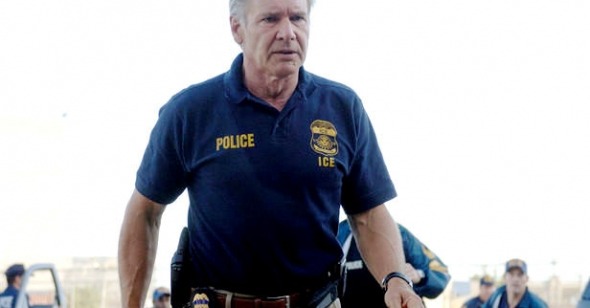

What do a busty wannabe actress from Australia, a 15-year-old Bangladeshi girl punished by the government for struggling to understand the mindset of the 9/11 hijackers, a lapsed Jewish wimp rocker, a Persian twentysomething rebelling against the strictures of her family by unbuttoning her blouse a bit too far, a Korean teen boy flirting with membership in a local gang, an African child without parents, and a Mexican factory worker with a young son have in common? Not much in reality. In Kramer’s world, they’re all illegals trying to stay in this country, and so, over the course of two hours, they cross paths with U.S. immigration policy as represented by hard-bitten (we know so because he drops f-bombs and watches shows about crocodiles at home alone) Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer Max Brogan (Ford), his partner Hamid Baraheri (Curtis, brother of the aforementioned Persian), application adjudicator Cole Frankel (Liotta), and his wife, Denise (Judd), an immigration defense lawyer. Naturally, all this shines the blinding light of truth on the inequities of our current system.

I don’t mean to trivialize the plight of those struggling to achieve a better life in the United States—it’s just hard to be credulous in the face of Kramer’s insipidness. Read back over that list of characters, and it should become painfully clear that Crossing Over is a screenwriter’s fantasy of immigration and wholly lacking in people one might ever actually encounter. When after Bishil’s earnest young Muslim delivers a speech to her class that argues for understanding the motives of 9/11 hijackers and the ICE shows up to deport her (back to what her defense lawyer sensitively dubs, a “third world garbage dump”), it’s hard to really care—she’s a construct, not a character, and exists only so that Kramer can check the “Muslim” box on his Films of Social Import application. I care even less about the plight of the young Aussie actress coaxed by Ray Liotta (shudder) into trading her body for a Green Card. Though, miraculously she is somehow made by Kramer to look even more callous than the agent who exploits her.

So much that’s so ridiculous happens in Crossing Over that it’d be impossible to fit it all in here, but one intersection is particularly noteworthy and emblematic of Kramer’s ham-fisted dramatics. Hamid, drunk and despondent after the murder of his sister, stumbles into a convenience store. Anyone looking carefully will have already seen that this convenience store is in L.A.’s Koreatown, and know that an earlier shot of Yong (our Korean Kid/stock East Asian) in the backseat of a car with a pistol will now pay off. And it isn’t long before five teens in ski masks bust in on Hamid mid beer run and kill the shop-owner. Hamid pulls his own weapon and levels four of the gunmen before turning on Yong. His negotiation tactic is straight ICE: “Hmm . . . I’m confronted by a boy with an accent, a gun, and a hostage. Let’s ask him how long he’s lived here and if he’s getting naturalized!” What follows is a gunpoint dissertation on, I kid you not, and I’m paraphrasing only slightly, the “spiritual awe one feels during the naturalization ceremony,” which Hamid has gone through and which Yong is slated for the very next day. Gack!

At some point it was decided that punctuating nearly every scene with languorous helicopter shots of Los Angeles freeways would make us ponder the interconnectedness of things and stuff. But this overused visual tic doesn’t stop Kramer from structuring a banging ending to pull it all together: The night after the shooting, at the big naturalization event where Korean Kid and Hamid’s Generic Conservative Muslim Father are about to take the oath, Max tensely confronts his partner about his sister’s murder while some dude in a bad suit vamps all over the national anthem in front of a massive Patton-sized American flag. It’s super ridiculous, but Kramer notches it up even further as Hamid’s brother—revealed responsible for the murder via a tasteless flashback that features his sister on all fours, buck naked with her lover—flees only to be met by police informing him how disrespectful it is to walk out on the national anthem. Thankfully the more relaxed coda finds Harrison Ford visiting the parents and child of the now-dead deported Mexican Factory Worker (Braga) he'd taken an interest in as he put her on the bus home in Tijuana and speaking awkwardly to them in Spanish. Crossing Over (almost) must be seen to be believed.