You Need to Wake Up

By David Schwartz

Solaris Mon Amour

Dir. Kuba Mikurda, Poland, no distributor

Solaris Mon Amour screens Friday, March 15, at Museum of the Moving Image as part of First Look 2024.

Polish author Stanislaw Lem and French director Alain Resnais were born a year apart (1921 and 1922); both were directly affected by WWII. Resnais left his apprenticeship as a film editor to join French forces occupying Germany and Austria after their surrender. Lem, of Jewish ancestry, spent the war avoiding detainment by Nazis in Warsaw and working with the Polish resistance. The specter of war haunts Lem’s fiction, as it does in the early films of Resnais, whose 1956 masterpiece Night and Fog remains the most thoughtful and viscerally powerful documentary about the Holocaust. Resnais and Lem created two of their most haunted works, the film Hiroshima mon amour (1959) and the novel Solaris (pub. 1961), at roughly the same time. In both, grieving protagonists live in dreamlike states, unable to escape jarring memories of lovers who died tragically. As painful as these memories can be, they also offer comfort; vivid recollections of past loves can help overcome the cold loneliness of the present.

Resnais’s Hiroshima is, of course, painfully real. Hiroshima mon amour includes newsreel footage of atomic bomb victims, and its story of the tentative love affair between a Japanese architect and a French actress (from the evocatively named town of Nevers) plays out in a damaged cityscape, with modern nightclubs and office buildings side-by-side with bombed-out structures. Lem’s science fiction novel is set in an imaginary but in many ways equally bleak world. On the distant planet of Solaris, the only living organism is an ocean that blankets its entire surface. This gelatinous entity, for reasons scientists are trying to determine, can materialize eerily lifelike replications of humans who live only in the memories of visitors to the planet. Solaris, which was written before Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space, offers a convincing depiction of a space mission. Most of the scientists are interested in encountering and studying forms of existence beyond the experience of humans. But Kris Kelvin, the protagonist, is heartbroken because of the death of Harey, his lover, who killed herself when he ended their relationship. He is amazed and disoriented when Solaris’s ocean offers up an all-too-convincing clone of Harey. With its space adventure, its philosophical speculations, and its exquisite ballad of doomed (and perhaps revived) love, Solaris has been adapted to film four times, most famously by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1972 and Steven Soderbergh in 2002.

Drawing inspiration from Resnais’s film and Lem’s novel (but mostly from the latter), the Polish director, film professor, and cineaste Kuba Mirkuda (who has made documentaries about Polish filmmaker-provocateurs Walerian Borowczyk and Andrzej Zulawski) has created in Solaris Mon Amour a one-of-a-kind archival masterwork, essentially adapting Solaris into a 47-minute film by poetically interweaving footage from 70 educational and industrial Polish films produced by the Educational Film Studio (Wytwórnia Filmów Oświatowych–or WFO) in Łódź, mostly from the early 1960s, and two different radio adaptations of Solaris (from 1962 and 1970). Industrial films are often employed for nostalgic camp value, but the WFO was a training ground for Poland’s top directors and cinematographers (including Wojciech Has, Krzysztof Zanussi, Piotr Sobociński, and Pawel Edelman), and the archival footage that Mirkuda uses is expressive and beautiful. The lyrical use of black-and-white in Hiroshima mon amour, its thematic inspiration, sets the tone for how Mirkuda has selected and treated the archival footage.

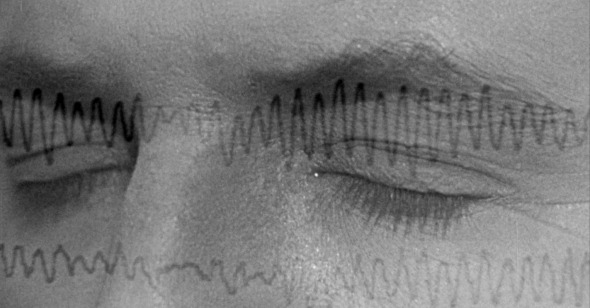

While the love story gives Solaris its emotional core, Lem is equally fascinated with the technology and science behind space travel and the potential for different forms of life in the universe to reveal the limitations of human consciousness. Throughout the novel, the need to “wake up,” becomes a refrain with multiple meanings—waking up from a dream, but also waking up from our limited understanding of ourselves. Mikurda and editor Laura Palewa scoured the WFO archives to find imagery that corresponds to the scope of Lem’s novel, from the cosmological, with images of planets and stars, to the microscopic, looking inside the human body. They also chose footage that is filled with the machines from the time; oscilloscopes, wires, large computers, rotary-dial telephones, typewriters, printing presses, and primitive space suits. Interspersed are images of film equipment, also now archaic: projectors, cameras, and strips of celluloid film.

Although we hear fragments of voice early in the film, we don’t see a woman’s face until nearly halfway through Solaris Mon Amour; this is followed by evocative and abstracted close-ups of a woman’s body. As in Lem’s novel, the scientific component gives way to the love story. By visualizing Solaris’s narrative indirectly, with footage from other sources that brings Solaris to life through association and suggestion, Mikurda has us interpret the film as though it is a dream of the novel. To Mikurda, this method reflects the way that Lem avoided directly addressing his traumatic experiences during the war, preferring the allegorical approach of science fiction. Sadly, but powerfully, this also becomes a way for Mikurda to reckon with his own personal loss. His romantic partner, Jagoda Murczyńska, died in 2022, in the early stages of the film’s genesis. (One of her contributions was to tell Mikurda about Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s adaptation of Solaris, a student project by the future director of Drive My Car).

Solaris Mon Amour (about the most meta-cinematic title one could imagine) is about cinema itself—a machine that puts us in a state of mind where dream, memory, desire, reality, and illusion blend, where outward adventures coexist with deep inner journeys. Towards the end of the film, Mikurda shows us the countdown of a film leader, associating it with the countdown to a spaceship launch; cinema and space travel, after all, are two kinds of journeys through time and space.