National Anthem

By Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer

El Juicio (The Trial)

Dir. Ulises de la Orden, Argentina, Impronta Films

The depiction of historical atrocities remains an irresolvable concern for filmmakers addressing genocide. In Argentina, renowned auteurs like Albertina Carri and Jonathan Perel insist there is no way to represent the violence carried out during the Dirty War—the military rule that spanned from 1974 to 1983—with films like Los Rubios (2003) and Camuflaje (2022), respectively. With his instructional 2022 film Argentina, 1985, director Santiago Mitre argues his nation’s recent history of state-sponsored violence must be dramatized in a way that makes its moral lessons unmissable.

In the documentary El Juicio, filmmaker Ulises de la Orden has edited 530 hours of courtroom footage from Argentina’s landmark 1985 Trial of the Juntas, in which the military officials who orchestrated the Dirty War are put on trial, to a lean three hours. Mostly using shots in which witnesses sharing their testimonies have their backs turned to the camera, de la Orden emphasizes their spoken memory while avoiding a visual exhibition of atrocities. Thus, he has created a vital political text that refuses to make a spectacle of cruel acts and foregrounds the bravery of victims, whose public disclosures have allowed Argentina to own up to its tragic past and carve out a new future.

El Juicio is divided into two parts, each made up of nine roughly ten-minute chapters. The film’s pacing acknowledges the severity of its content, as the breaks between chapters offer moments to process the crimes discussed before bearing witness to another leg of the trial. De la Orden’s focus on slight gestures, glances, comments, and sighs proves engrossing, highlighting the filmmaker’s ability to transport viewers to a precise moment in time. The long runtime benefits this temporal displacement, awarding us more time to get lost in the trial and come to terms with the heaviness it bears.

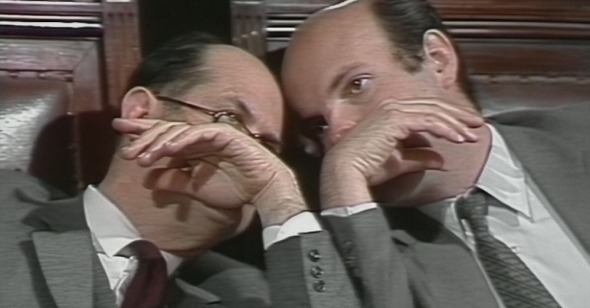

Over the course of the film, the nine defendants begin tripping over their claims. At times, they call the Dirty War a nasty but necessary act, while at others they completely deny the existence of a war, claiming that period in Argentinian history can only be described as pure chaos. In these moments, it becomes clear the defendants are desperate to find ways of escaping their situation. Similar moments in which the defense attempts to stall the trial by arguing about seating accommodations and buggy microphones offer a clearer window into last-ditch attempts at avoiding justice, which, contrasted against the vocalized sorrows of their victims, appear humiliating and provides the film with a bit of levity, and much of the film’s drama rests in these contrasts.

Central to these exchanges are the words that occupy the spaces between them. El Juicio proves an exceptional dialogue drama, swinging among opposing versions of history until only one remains. De la Orden’s use of soundbites as epigraphs at the beginning of each chapter acts as another narrative anchor. These short phrases provide a powerful throughline by which to read the film, developing into an aphoristic companion to Argentina’s Nunca Más Report, the 400-page exposé of the military dictatorship’s crimes that lead prosecutor Julio César Strassera invokes in his final address to the military officers on trial. These citations, alongside the film’s overall reliance on witnesses’ spoken testimonies, emphasize the importance of oral history as a collective form of remembering, especially since the truth often slips or is actively suppressed by governing bodies.

El Juicio has a patchwork quality, combining crisp found footage with blurry extracts from multiple U-Matic tapes and the occasional black-and-white flourish, capturing the different ways in which the country first experienced the trial on television. Assembled together, these tapes situate the viewer as another witness to history as it unfolds, each sudden blur eliciting the same threat of interruption it did in 1985. The notable damages in the film’s makeup, though inherent to the quality of its sources, recognizes the material nature of its archival footage. El Juicio’s blips and blurs offer a model for a national cinema that isn’t pristine and grandiose, but rather blemished and humble in its sampling of reality.

With his subtle approach to editing, de la Orden preserves the political immediacy of the moments he chooses to include. He decides to not add a soundtrack to the film, letting each testimony play out against the unpleasant silence of the courtroom. Their matter-of-fact presentation reflects how the dictatorship’s crimes were carried out in a matter-of-fact way. The atrocities discussed will always elicit horror, but their public acknowledgment throughout the film represents a catharsis for Argentina. In one of the film’s final moments, de la Orden zooms in on a woman weeping as the public applauds Strassera’s closing remarks, an expression of simultaneous tragedy and victory. A political work of intense human feeling, El Juicio plays like a memory transmitted from one generation to another.