We Can't Work It Out

by Peter Kim

Climax

Dir. Gaspar Noé, France, A24

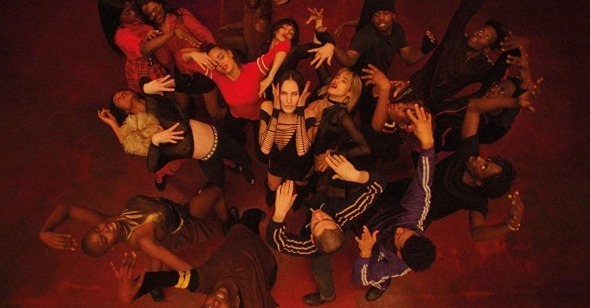

Early in Gaspar Noé’s Climax, the young women and men of the film’s central dance troupe are rehearsing in a school auditorium. The troupe is spontaneous and captivating; filmed in one fluid, rhythmic, continuous shot, the performance holds the camera under its spell. The dancers give varying physical expression to libidinal desire. The choreography, the techno-pop soundtrack, the way in which the camera moves gently forward, backward, overhead, conspire for a cinematic effect that is Noé at his technical best—the sequence is perhaps the most enjoyable of his career. Where Climax goes from here, however—how the film represents the inner lives of young millennials and deals with au courant issues of diversity and collectivist politics—is far more objectionable.

Climax was picked up for distribution stateside by A24 and financed in part by VICE Films, companies with a recent track record of content marketed for and by millennials, and an interview montage prior to the dance scene functions, perhaps, to clarify who will be the film’s subjects, and to exactly what demographic the film is aimed. This young group of dancers is pointedly diverse: women, men, non-binary, queer, black, white, French, American, and German. Noé captures in these interviews the anxiety over failure that anyone pursuing a career in the arts not born into wealth would know well. One dancer is asked, “If you couldn’t dance, what would you do?” and responds “suicide”; another dancer is asked, “Are you willing to do anything to succeed?” to which he says, hearing the sinister subtext of the question, “I’d do anything.” The professional ethos of “do what you love” is revealed for what it has become, a mask for the poverty of opportunity and financial support that fuels an artist’s sense of dread and desperation.

The film appears to be at its most sympathetic to the dancers in these early interviews. After the big dance number, the film shuffles between static shots of different conversations happening simultaneously in the auditorium. The idea for Climax, Noé remarked in an interview, started as a documentary about street dancers, and these seems the most traceable in these scenes, which seem designed to give a sense of how millennials talk when no one is watching. Some of the conversations are familiarly juvenile, to be sure—young men talking about the size of their genitals—but beyond that, all of the conversations involve a flip disregard for any and all institutions: God, the French national flag, the auditorium, marriage, monogamy. The dancers’ casual irreverence ultimately feels one-dimensional, as if these youths are walking caricatures that an older guard could easily write off as naïve.

At one point in the film, Selva (Sofia Boutella), the character who comes closest to resembling a protagonist, is asked by another dancer whether she has ever had an abortion. After a deliberately enigmatic pause, Selva responds, “It’s nice to have the option, you know?” After this, the words “NAITRE EST UNE OPPORTUNITÉ UNIQUE”[Birth is a unique opportunity] flash across the screen. As Noé’s response to Selva, the text comes across either as tongue-in-cheek or as a serious, ethical rebuttal to Selva’s flip comment. What level of irony are we meant to attribute to these words, which almost sound like a “pro-life” talking point? It is one thing to open up a film to a moment of productive ambiguity or to foreclose an easy resolution, but Climax willfully engages in purposeful frustration. In this sense, Climax is no different from Noé’s previous work. What makes Climax different, however, from such films as Irreversible and Love—films that are oddly romantic and anchored in their characters’ inner lives—is its veiled political message. The latter half of Climax seems to express a reactionary skepticism for the idea that genuine diversity is socially possible, and that a unified collective could really take shape among people of different races, classes, and sexualities.

This skepticism is slyly communicated through what becomes the central conceit of the film—that someone has spiked the punchbowl with LSD, and everyone, including the eight-year-old son of one of the dancers, has been drinking from it. The temperature of the auditorium gradually shifts. Gone is the feeling of camaraderie among the assembled troupe of queer and multiracial dancers, replaced with paranoia and naked aggression. We are exposed to a dizzying carnival of human cruelty. The continuous roving shots familiar from Noé’s other films follow the dancers around as they stumble and cry. These unbroken takes feel like punishment, as if to ensure that the dancers are not allowed a moment’s reprieve. In one scene, a dancer pulls a knife out against a crowd of hostile dancers who believe that she is the one who has spiked the punchbowl. There is an unexpected turn in which she goes from directing the knife at the others to redirecting it toward herself, internalizing the other dancers’ hatred and making it her own. And at many points during the latter half of the film we hear the desperate screams of the eight-year-old boy, tripping on LSD, locked in an electrical closet.

Climax’s various spectacles of psychological and physical pain can distract from the strangely conservative logic that underwrites to whom violence is done and why. A pregnant dancer is brutally kicked in the stomach; the child is left to die in the closet; Selva rejects her straight male love interest’s advances, and the same male love interest is beaten unconscious. What suffers the most from this LSD-induced breakdown of social order is the sanctity of distinctly hetero-normative values: the innocence of the child, the heterosexual couple, the pregnant mother. Rather than question the ways in which these tropes are accorded normative value, the film seems to actually lament their disfigurement.

It’s also worth questioning how Noé fits within the contemporary political climate of both France and the States, in which shock and spectacle have been most effectively mobilized by the far right to erode the legitimacy of democratic institutions. (One shouldn’t forget the antics of French presidential candidate Marine Le Pen who, in 2015, posted images of beheadings carried out by ISIS, including the killing of American reporter James Foley, on her Twitter account, to bolster her anti-immigrant agenda.) The danger is not so much that a spectacle of shock would rile the viewer into an emotional fervor. The opposite seems more likely: inured to shock, the viewer would rather feel nothing at all in the face of abject cruelty. That the film ends with the arrival of soldiers in camouflage wielding rifles and flashlights, signaling the symbolic reinstitution of the Law, is telling for how Noé casts the demise of the dancers’ initial cohesive diversity. Climax ends far from the optimism of its opening. In the morning aftermath, against the dancers’ semi-conscious bodies, text flashes across the screen: “VIVRE EST UNE IMPOSSIBILITÉ COLLECTIVE” [Living is a collective impossibility].

Climax’s thinness of plot in general and in the second half in particular (which could be simply described as a shared, hellish LSD trip), along with the film’s textual interjections, contribute to the sense that Noé, more than ever, has an axe to grind. Is Noé then a 21st-century Edmund Burke, casting this young troupe of dancers as thoughtless libertines? Is Climax a cynical repudiation of a young generation’s promise of queer diversity and multiculturalism? Perhaps, but the film also opens itself up, perhaps unintentionally, to a critical, leftist response. If LSD works in the film as a conceit to reveal the deep fractures and individual cruelty lying just behind its pretty, millennial veneer, the alternative need not be to trade in a cheap, blanket cynicism. Rather, it speaks to the sobering difficulty of exploring diversity beyond the surface level across class, race, and gender; it also means wresting the very concept of diversity away from neoliberal or corporate agendas, and instead using the term to think critically and patiently about social institutions. Climax serves as a reminder of the depths to which we can descend in our cruelty towards one another if we choose not to do so.