Risky Business

By Adam Nayman

Call Me by Your Name

Dir. Luca Guadagnino, Italy/U.S., Sony Pictures Classics

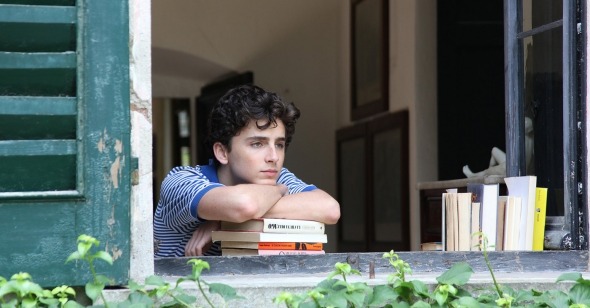

There is an extended passage in Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me by Your Name organized around the presence, always in different positions and locations relative to the camera and the characters, of a wristwatch. The timepiece belongs to Elio (Timothée Chalamet), an American teenager who previously hasn’t had much use for it, minutes and hours being a relative concept during a sweltering summer vacation in Northern Italy. When there is no schedule to be kept between dawn and dusk, time is scarcely of the essence.

But now Elio has made fixed plans at midnight to meet Oliver (Armie Hammer), the graduate student billeting in the guest bedroom next to his. The two have already kissed secretly in the grass by the side of a dirt road; they would seem to be on the way to becoming lovers. Elio’s patience is suddenly disrupted; the afternoon and evening stretch out ahead of him like a distant horizon line. He goes about his day as normal, taking meals with his family, playing the piano in the parlor, and even having sex with his girlfriend, all seemingly spontaneously, and yet in actuality set to the rhythm of his own personal, internalized countdown.

At no point in this sequence, which spans some ten minutes of screen time, does Guadagnino cut to a close-up of Elio’s watch, and this pronounced show of restraint within a lyrical conception gets at some of what’s so impressive about Call Me by Your Name. It’s easily its director’s best work, and probably good enough to change the minds of those who’d previously written him off as a flashy, pushy wannabe à la Paolo Sorrentino. Like his diabolical countryman (except thankfully lacking Sorrentino’s papal sense of self-importance), Guadagnino worked in his early films to turn every single onscreen gesture—the preparation of food, the exchange of personal totems, diegetic needle-drops—into capital-M Moments.

The results varied between hysteria and embarrassment (the two main takeaways from I Am Love) and, occasionally, borderline sublime bits of business like Ralph Fiennes’s transported, body-and-soul vamping to “Emotional Rescue” in A Bigger Splash, a movie whose title conveyed the appeal of its director’s more-is-more philosophy, as well as its inherent drawbacks. While mostly convincing as a fable of idle island horniness gone murderously wrong (evoking everything from its source material, La Piscine, to The Talented Mr. Ripley), A Bigger Splash, especially in its late-stage transformation into a finger-wagging political parable against the evils of privilege, felt like the work of a filmmaker trying to do too much.

Call Me by Your Name doesn’t overstep itself in the same way, which is not to say that it’s slight or slender or any of the other synonyms that might suggest simply a well turned minor piece. On the contrary: in adapting André Aciman’s 2007 novel, Guadagnino and screenwriter James Ivory have produced a film that simultaneously analyzes and dramatizes issues of sexuality, religious identity, and, once again, privilege—with enough well-read bourgeois lazing about in the sun to give Michael Haneke hives—and yet without straining against its clearly marked narrative boundaries as a coming-of-age romance, or exploding its form as an accessible, fundamentally pleasing upper-middlebrow entertainment.

This is not meant as a reduction, or as damning with faint praise. It takes a tremendous amount of skill and intelligence to produce a movie that possesses potentially broad appeal without sacrificing complexity or seriousness. It’s not as if Guadagnino has turned into an ascetic overnight, either. Rather, working with the gifted Thai cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom (who shot Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives and Arabian Nights), he’s refined his style into something poetic rather than bombastic. Instead of hammering, Guadagnino chisels; rather than insisting on his images, he trusts his canted, intimate compositions to do their work. He doesn’t go too far, or even really threaten to, except maybe for a few blaring Sufjan Stevens music cues, which are very much a your-mileage-will-vary proposition. And most importantly: he doesn’t cut to a close-up of that wristwatch.

There are other significant but subtly deployed props in Call Me by Your Name, starting with the Ray-Ban sunglasses perched precariously on Elio’s always-tilted head—a clever way of reminding that the film is set in 1983, the year of Risky Business. There is more than a little of the young Tom Cruise in Chalamet’s acting, particularly his springy physical comportment as he glides through his family’s summer home or sprawls on lawn chairs in the backyard. He’s a gorgeous and brilliant kid, and he knows it, and he bops and shimmies accordingly. It’s easy to imagine a version of this story where the young, untutored protagonist’s comparative lack of worldliness next to his older secret crush leaves him unsteady on his feet, but Guadagnino and Chalamet go in the other direction, emphasizing Elio’s talent (he’s an ace piano player), grace, and confidence as he puts himself discreetly but unmistakably on display for Oliver, who in turn comes to seem comparatively uncomfortable in his own (perfect, tanned, tautly muscled) skin.

If there’s a potential weak spot here, it’s Hammer. Not his acting, which is precisely as charming as it needs to be, but his casting as a 24-year-old Jew, which strains credibility on both fronts. And yet I’m inclined to forgive, because Hammer is good, and because Oliver’s slightly implausible physical and intellectual superiority, and the ways that it’s humorously and then touchingly undermined by his attraction to Elio, is necessary to give Call Me by Your Name its humid air of desire, as well as the slightly enchanted feeling its ancient setting demands. Elio’s father (Michael Stuhlbarg) is an expert in antiquity, and in one scene, he takes both of the boys to the beach to help retrieve a sunken classical statue, whose perfect, Apollonian proportions are contrasted with Oliver’s own. Elio’s upbringing in an educated household has acquainted him at an early age with the perfection and appreciation of forms, which in turn gives Hammer’s movie-star handsomeness a viable context in which to mesmerize the camera.

As for Oliver’s unlikely Jewishness (signified by the Star of David he wears around his neck, again rarely, if ever, shown fully in close-up), it can be connected to the script’s underlying motif of difference, namely, whether it’s something that can be perceived by others, or else protected carefully against its own visibility. Elio and Oliver’s fast friendship does not set off any immediate alarm bells within the small, conservative town, because it looks basically identical to all the other hearty homosocial bonding going on in the bars and bike paths. Their extended, intricate flirtation passes unnoticed even as it’s out in the open. But the air is also pressurized. During one outing, Elio and Oliver stop at a house to ask an old woman for a glass of water, and she provides it before returning to her chair, which is positioned beneath a huge portrait of Mussolini. The paradisical vibe of the location—and even the extremely comfortable economic position that Elio’s parents now occupy within it—is framed against the remnants of a not-so-long-ago fascism; when Stuhlbarg’s Professor Perlman refers to himself and his family as “Jews of discretion,” it’s a laugh line laced with anxiety.

There’s something quite touching about watching Stuhlbarg in Call Me by Your Name eight years after his breakthrough in A Serious Man (also a movie about Jews of discretion). For the Coens, the actor expertly pantomimed a kind of timeless schlemiel—an archetype on the verge of stereotype, God’s lonely straight man. Here, once again playing a Jew with tenure, he feints at similar stylization, threatening to turn Perlman’s jolly, indulgent man-of-letters largesse into a joke before revealing his performance—and with it, the character—as something more surprising and substantial. The bildungsroman cliché that parents just don’t understand is inverted in a late exchange between Elio and his father regarding the outcome of the former’s affair that is far more than the For Your Consideration clip it’s been hailed as (or scoffed about) since the film’s bow at Sundance. The slightly halting, and yet completely compassionate and open-hearted, content of the Professor’s speech to his son, which encompasses tones of pride, empathy, encouragement, commiseration, and, just as delicately and perceptibly as Ivory’s script intends, a curious sense of regret over roads untaken, provides a rare example of a movie clearly articulating its themes without overstating them. And all this without either character ever really coming out (double entendre: mine) and saying precisely what they mean.

Not everything in Call Me by Your Name is so thoughtfully layered. Where ideally Elio’s exploitative treatment of his lover Mariza (Esther Garrel) would hover significantly over his own ultimate romantic disappointments (just as her naive fixation on him as an ideal mirrors his enthrallment with Oliver), instead it’s hastily excused and allowed to evaporate. And while it’s clear that a lot of thought has gone into the film’s unusual, asymmetrical structure, which meanders slowly and pleasurably toward a well-established, pre-determined endpoint (i.e. the impending end of Oliver’s trip) only to then hurtle past it in a series of false climaxes, the running time begins to feel heavy in the home stretch. It’s also very much worth asking, given the erotic charge Guadagnino and Mukdeeprom lend to nearly every object and body in view, if Call Me by Your Name’s somewhat sanitized and withholding depiction of gay sexual intercourse—a lack of explicitness noted but not yet significantly called out by critics—affirms an aesthetic rooted in clandestine sensations or exposes its makers as, to some extent, art-house entertainers of discretion.