A Room of Their Own

by Jeff Reichert

Afternoon

Dir. Tsai Ming-liang, Taiwan, no distributor

Tsai Ming-liang’s formal economy, which has grown ever more rigorous over the course of his career, has often led some to label him a minimalist. He may rarely move his camera, but think for a second of all the maximalist explosions of desire and feeling he’s placed in front of it: sex of every kind, voracious gustatory consumption, rapturous musical numbers, and that exquisite, aching longing for human connection that’s been his mainstay and trademark. He’s a filmmaker whose most recognizable images are tableaux of lonely humans caught in the act of devouring—a lipsticked head of cabbage in Stray Dogs, a highly sexualized watermelon in The Wayward Cloud, a nipple in Vive l’amour. Tsai’s films are filled to the brim; his static frames, then, seem a tactic of trying, at any cost, to hem in some of that energy and transmit it to his viewers. If he didn’t hold his images fast, his characters and films might explode.

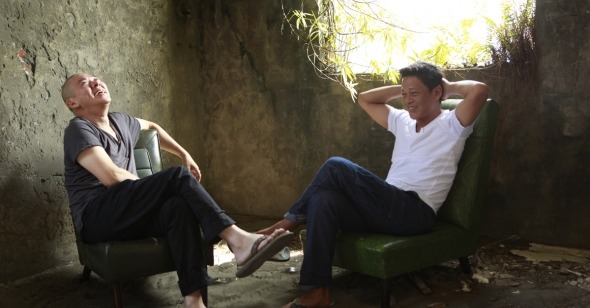

He’s probably never made a movie out of less than he has with Afternoon, though his Walker series of shorts, in which his usual star Lee Kang-sheng dons a monk costume and walks ever so slowly through bustling urban spaces, come perhaps closest to this film’s ascetic approach. In Afternoon, Tsai and Lee sit side-by-side facing the camera in an unfinished room in the home they own together and just talk and smoke and drink water or coffee. And then talk some more. The film’s four shots (the camera operator breaks at regular intervals to reload, leaving a few seconds of black) run across two hours and twenty minutes, and that’s all there is to it. It’s the old complaint about so-called “art” films—that they’re nothing more than people sitting around talking—taken to the extreme, and it’s Tsai’s most baldly naked film. As he has throughout his career, he’s there’s complexity and density to his scarcity and simplicity.

Afternoon reaches its emotional peak early on as the 59-year-old director, still reeling from health scares that hit him during and after the production of 2013’s Stray Dogs, discusses his mortality. Tsai feels death is near for him, and he tears up as he contemplates with his longtime companion what his life will be like without him, wonders about the movies that they have not yet been able to make, and eventually offers his sincere thanks to Lee for the time they’ve had together. This confessional section leaves the dirty, decayed, granite room in which they sit (it feels like a setting omitted from Stray Dogs) thick with emotion. Even Lee, whose blank deadpan has made him one of cinema’s greatest silent comedians, seems struck by Tsai’s open admission of mortality and gratitude. The force of the film’s spare simplicity here reminds of the similarly devastating No Home Movie—artists of the caliber of Tsai or Chantal Akerman need no tricks to move an audience, only honesty and fearlessness.

The purpose of Afternoon, as stated by Tsai to Lee, is an expression of gratefulness, but not just from director to actor. What is their relationship, you might wonder as the film continues. At first, Tsai talks of how the pair “got together” and almost “broke up” after a particularly stressful period in which a swindler ran off with grant money for a film and forced Lee’s mother to lose her apartment—playing into rumors that have swirled around them that the two are longtime lovers. Later, they openly discuss the gap between their sexual preferences (Tsai acknowledges his own homosexuality; Lee acknowledges the woman with whom he’s fathered a child, Tsai’s godson) and how Lee’s family might feel about him having lived so long with a gay man. The closeness between them is beyond friendship, beyond mentorship. But it’s also inextricably linked to business: Lee, who says he is currently trying to get more work as an actor with other directors, notes that he tells all prospective suitors he’ll always work first for Tsai, who has approval over all of the scripts he accepts. Later, Tsai describes their relationship as almost familial, though we have two decades worth of film collaborations between the pair in which Lee’s body has been lovingly filmed in all sorts of states of undress and sexual activity that would suggest that such a term is inadequate. Though their dialogue at times has the quality of a tell-all, it lands about as conclusively as Jodie Foster’s “announcement” about her sexuality at the 2013 Golden Globes, which is to say: not conclusively at all.

Is Afternoon ultimately a just-for-the-fans document? It could be ungenerously viewed as such given that it’s a record of an artist obscure outside of cinephile circles going over his life and career with his leading man in a discussion peppered with references to the features, shorts, and plays they’ve made together. Even within this limited scenario, Tsai can’t help but deliver something more. Consider the deceptively simple frame, which places the deep, dark corner of the crumbling room near-dead center, drawing our eye to the image’s intriguing depth, or how the camera is set high enough that the pair of pane-less windows open out onto the lush green jungle beyond. The room is meaningful to Tsai’s life (he and Lee live in that house) and its contrast of manmade dilapidation and verdant nature visually recalls his films, but it’s mainly just an objectively beautiful composition to gaze upon for a while. And the conversation between the two men, for all its references to unseen works, is so empathetic, and circles back so regularly to universal human concerns—the difficulties of companionship, especially—that a viewer bearing no familiarity with Tsai or Lee might well be charmed and moved by the frankness of their talk.

“What else?” Tsai prods Lee again and again any time conversation flags, usually only to bring up a new topic and keep chatting away himself. At times a voice from offscreen (perhaps cinematographer Lai Tian-jian) asks a question to keep things flowing, providing a reminder of the world outside the static frame. Indeed, as the credits roll and the names of the film technicians flit by, you realize that even though all we ever saw in that room were Tsai and Lee, there were at least a half-dozen or so other artists nearby, all participating, albeit silently, in the making of Afternoon. Nevertheless, the film is all about the two of them, and ultimately that fundamental and mutual expression of gratitude. It’s the continuation, and hopefully not the culmination, of a conversation these two vital artists have had with each other via their work over the past two decades. And even when they get up and leave the room vacant at the end, as with all the films they’ve made together, the feelings persist.