The Muckraker and the Murderer

By Eric Hynes

Tales of the Grim Sleeper

Dir. Nick Broomfield, U.S., HBO Documentary Films

Of all the things one can say about Nick Broomfield—and there are many things to say, as the record below will show—one can’t say he doesn’t have conviction. Yes, he seems to like the sound of his own voice, which tends to be audible during on-site interviews as well as via voiceover narration. And yes, he seems awfully keen on casting himself as the protagonist of his own investigative documentaries. It’s hardly a Nick Broomfield movie if Nick Broomfield doesn’t appear, mid-stride in the street, headphones on and microphone extended with a shit-savored-grin forming, calling after someone who’d rather not be called after. But for all of the evident relish Broomfield has for the chase, the bum-rushing of sources, the turning over of rocks, the without-a-net-leaping into hostile environments, he does seem to be motored by real discontent, disbelief, and dismay over whatever bullshit he’s being fed.

Much like Errol Morris excels when his subjects aren’t as media savvy as he is (his interrogations of Robert McNamara and Donald Rumsfeld are like watching heavyweights spar to a draw—fascinating, but frustrating); Werner Herzog excels when he’s in awe, rather than in command, of his subjects; and Michael Moore excels when he is rather than plays the underdog, Broomfield’s work elevates when his reportorial instincts are stoked by outrage rather than outrageousness. A film like Kurt & Courtney may bring it in terms of slow-motion-car-crash entertainment value—it was a favorite among college-aged clerks during my years at Kim’s Video—but Broomfield’s condescension in both approach and presentation can be toxic. By contrast, with hybrid narrative Battle for Haditha, which recounts the moment-by-moment, real-life events that led to a massacre of innocents in Iraq, he’s too committed to bringing tragedy and injustice to light to bother casting that light back on himself. Haditha may not be “fun” or entirely successful, but it does add up to something greater than chasing after gotcha moments. (Biggie and Tupac falls—fascinatingly, frustratingly, at moments even transcendentally—in between.)

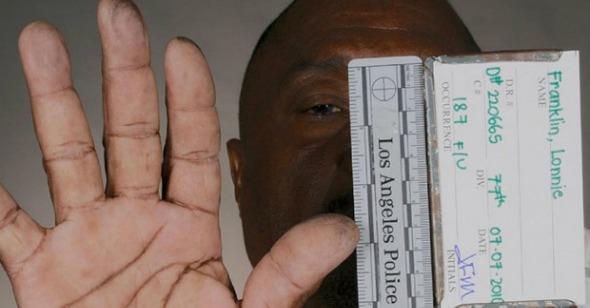

To that end, things don’t start very promisingly for Broomfield’s latest, Tales of the Grim Sleeper, in which the director tries to understand how a serial killer, Lonnie Franklin, managed to operate for several decades, very nearly in plain view, without anyone in his South Central Los Angeles community taking notice. Broomfield’s voiceover narration breaks in immediately, and his first round of interviews on the streets of South Central are bracingly patronizing. When an interviewee utters the slang “jibbity,” Broomfield echoes it back, savoring the sound like it’s a charming little bauble rather than an effort to communicate. And the decision to show the director being leapt upon by a barking guard dog—much like a later scene in which gunshots are overheard during an interview in an alleyway—seems geared toward establishing the filmmaker’s bona fides, his fearlessness in the face of danger, and thus toward creating separation between the film/filmmaker/audience and the people and places we’re visiting. (Within the parameters of the film, those gunshots are anecdotal; within the lives of those we see pass before us on the streets, those gunshots are a pervading reality.) That Broomfield and his small crew make their way through South Central in a tidy black BMW doesn’t exactly counteract this impression.

But soon Broomfield finds his footing in the narrative, subordinating his persona to the testimonies of local witnesses and letting his outrage take over. An initial round of interviews with Franklin’s neighbors yields little but resistance and denial—his male friends, in particular, extol the good-guy-ness of one suspected of dozens of brutal homicides—but soon different stories are told. Whether motivated by conscience clearing or delayed consciousness, associates of Franklin start following up with Broomfield, circling and circling around stories and interactions that point to something clearly suspicious, and increasingly damning about their neighbor. A simmering misogyny, seemingly stoked by a failed marriage to a crack addict. A taste for rough and perverse sex with prostitutes, which he took to documenting photographically. Driving around the neighborhood at night and bragging to friends that he was “cleaning up the streets.” Hiring acquaintances to dispose of bloodstained vehicles. Working, unsupervised, at a garbage disposal facility where evidence could easily be made to disappear.

These testimonies don’t really serve to confirm Franklin’s guilt—while the film cannily doles out the damning evidence, his guilt isn’t really in question—but rather expose the self-delusion of those around him. For both the men and the women in the community, a strong motivator behind that self-delusion was money—he was paying impoverished people to perform tasks about which they were expected to ask no questions, be they dudes taking on (very) odd jobs, or prostitutes turning tricks. There’s another movie to be made about this psychological and social phenomenon—Franklin seemed to function as a living, breathing apparition on the block, essential to its tenuous economy but effectively invisible—but what drives Broomfield is a deep skepticism about how the case has been handled by the authorities. How did the L.A.P.D manage to miss all of these clues for nearly three decades while dozens upon dozens of young women went missing? Were they complicit in the killings, tacitly allowing Franklin to “trim the hedges” of poor black prostitutes? Were they unwilling to dig deep into a community as untrusting of the police as South Central? And why, Broomfield asks, during an emotional flourish of a finale featuring a montage of interviews that coalesce into a super-narrative of predation, haven’t the cops or the D.A.’s office interviewed numerous survivors of Franklin’s terror?

There’s no shortage of compelling footage here, or of provocatively arranged sequences. Foremost is a stretch involving Franklin’s son and possible collaborator, Chris. First we learn that a neighbor has been beaten by Chris’s associates, supposedly for talking to Broomfield. Then, after hearing of repeated attempts at contacting Chris, he consents—shockingly, of course, thanks to the dramatic setup—to an interview. The camera watches Chris walk toward the car and get in, the possibility of violence fully present in our minds. His testimony turns out to be less threatening than conflicted, full of discomforting memories and understandably warped yearnings. “I lost my best friend,” he says, bemoaning his father’s incarceration.

While Broomfield’s films benefit from conviction, their power rarely derives from evidence gathering, and this is certainly true of Tales of the Grim Sleeper. As pointed out by colleague Manohla Dargis outside of a screening at the Toronto Film Festival, much of what’s recounted in the film was previously reported by Christine Pelisek, who spent several years piecing together the story and its aftermath, and continues to report on Franklin’s trial, for the L.A. Weekly. (Pelisek is never mentioned in the film, but Broomfield does take a swipe at the L.A. Times—see what he does there?—for underreporting the story.) And Broomfield’s taste for sensationalism has a tendency to undo his serious reporting, such as when a final voiceover wonders if any other killers are “out there,” which I can only assume was meant as a call for greater community vigilance going forward, but actually comes off as rank fearmongering—not to mention seeming to suggest, out of the blue, that someone other than Franklin might be guilty of the murders. While that’s not likely Broomfield’s intent, such phrasing certainly serves dramatic effect more than reportorial precision. And while Broomfield might be more impresario than reporter, he’s not exactly shying away, in form or style, from assuming the mantle of the latter, and thus can certainly stand to be scrutinized as such (while not, out of respect to his artistry, evaluating him solely by those standards).

As with Biggie and Tupac, the film is most potent when the chase leads us to taking the full measure of people like Pam, a former prostitute and crack addict who takes over the film for long stretches. It’s through Pam’s comedic and empathetic interactions with neighbors, working girls, and Broomfield himself that the complex culture of the community starts coming into focus. When Pam’s onscreen, you hardly care where Broomfield might be leading you next, which he’s smart enough to realize and roll with. He does something similar with Margaret Prescod, an activist for Black Coalition Fighting Back Serial Murders who’s fought for decades to call attention to the murders and missing people in the community. Prescod is an amazing talker—she’s knowledgeable, sharp, and damningly on point—and Broomfield wisely refrains from staging scenes that put him alongside her (which he does do with Pam, though to a rather endearing “can I just be your straight man?” effect). Such ceding of the spotlight is what gives the final roll call of survivors such weight. The cause and effect of what led us here, and where it will lead, as Franklin goes to trial and the community processes what it has endured, isn’t as important as simply giving voice to those who’ve been ignored, forgotten, and most unfathomably, wished dead.

It’s in these circumstances that Nick Broomfield, star of the films of Nick Broomfield, alights upon his most useful function. After threatening to take up too much space in the story, he finally backs away and lets his subjects take over. He goes from conduit—sometimes necessary, sometimes a nuisance—to just another apparatus of the film, a scrim to look through to some kind of truth that we might not otherwise get a chance to see.