On Paper

by Jeff Reichert

The 50 Year Argument

Dir. Martin Scorsese and David Tedeschi, U.S., HBO Films

Martin Scorsese‚Äôs new documentary, The 50 Year Argument, codirected with David Tedeschi, suggests a nonfiction companion piece to the angry, audacious The Wolf of Wall Street. After an opening invocation, in which a voiceover quotes an Oliver Sacks essay entitled ‚ÄúSpeak, Memory,‚ÄĚ read over sanguine helicopter shots peering down into the caverns between Manhattan‚Äôs skyscrapers, we‚Äôre thrust into rough footage from the Occupy Wall Street protests (the third anniversary of which fast approaches as this film enters the world). Writer Michael Greenberg recalls how a phone call from New York Review of Books editor Robert Silvers led him to complete a story about the scene in Zuccotti Park that would later be published in that journal, and he reads from his article over images from the protests, a formal strategy that will be repeated with other NYRB texts throughout The 50 Year Argument. Greenberg captures that inchoate rage against Wall Street titans run amok; Scorsese‚Äôs previous film rendered Jordan Belfort as their spiritual progenitor, the starting point of a systematized move towards the valuation of money over culture and knowledge.

That passage by Sacks was drawn from a piece run in NYRB in 2013, and it‚Äôs worth excerpting parts of it here, so well do they encapsulate not only the thesis of The 50 Year Argument, but something of the methodology of Scorsese‚Äôs engagement with history, memory, and community in his films: ‚ÄúOur only truth is narrative truth. The stories we tell each other and ourselves . . . Memory arises not only from direct experience but from the intercourse of many minds.‚ÄĚ For the good of all, stories need to be captured and transmitted; if left only to the individual they might well have never existed. Scorsese, a believer in stories who has chosen cinema as his chronicling medium, here turns his lens on a venerable literary journal, where the words ‚ÄúReview of Books‚ÄĚ only encompass a part of an altogether more ambitious project.

The New York Review of Books was founded fifty years ago during the 1963 printers‚Äô strikes, which shut down six major papers in Manhattan, including the New York Times. Four friends, Jason and Barbara Epstein, along with their neighbors, the poet Robert Lowell and his wife, writer Elizabeth Hardwick, first came up with the idea as, according to Jason Epstein, the New York Times Book Review was at that time ‚Äúreally a disgrace.‚ÄĚ The moment was ripe‚ÄĒas Silvers, enlisted by the group from his post at Harper‚Äôs, recalls, ‚ÄúThe publishers were going crazy . . . Books are coming out, but there was no place to advertise. Jason, a great publisher said, ‚ÄėThis is the only time we‚Äôll be able to start a new book review without any money.‚Äô‚ÄĚ Their unifying ideology comes from a Harper‚Äôs piece written a few years earlier by Hardwick and edited by Silvers entitled The Decline of Book Reviewing: ‚ÄúThe flat praise and the faint dissension, the minimal style, and the light little article, the absence of involvement, passion, character, eccentricity‚ÄĒthe lack at last of the literary tone itself have made the New York Times Book Review into a provincial literary journal.‚ÄĚ One imagines Scorsese is well aware that, today, we could easily retitle the article ‚ÄúThe Decline of Movie Reviewing‚ÄĚ and probably not have to change a great deal of Hardwick‚Äôs argument.

Having sketched out the journal’s early history, The 50 Year Argument proceeds without any attempt at building a chronology of the NYRB, or evincing much interest in tackling its raison d’être (book reviews, namely) focusing instead on the meaty cultural criticism that it’s rightly become famous for. Along with its long reviews of new titles, every issue features writers of note wrestling with the issues of the day and throughout the film we hear from many of the journal’s most famous contributors: James Baldwin discusses race, Joan Didion reads from her analysis of the Central Park jogger case, Susan Sontag talks on feminism, and Václav Havel relates tales of the Velvet Revolution. Interwoven with the writings is archival footage spanning the twentieth century, creating visual links with the voracious range of topics covered by NYRB; Scorsese and Tedeschi are concerned less with the minutiae of running a publication than with placing that publication within the context of the events that influenced it and vice versa. It’s the opposite of the generic approach taken by Andrew Rossi’s New York Times puffier Page One, which for all its lack of specificity and context, could have just as easily been a film about the Toledo Blade.

The 50 Year Argument makes not just a compelling case for the importance of a publication the New York Review of Books but also, by its conclusion, for the written word itself. The film is something of a paean to the value and power of the editor‚ÄĒnot just as a figure who helps writers communicate their ideas in clear sentences, but as one who shapes the overall voice, tone, and concerns of a publication over time. The film detours midway through into a long chunk of footage from D. A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus‚Äôs 1979 barnstormer Town Bloody Hall, a document of one of the maybe last moments in American culture where a battle of ideas also equaled great entertainment. It‚Äôs a crystallizing inclusion‚ÄĒthe filmmakers imply by its usage that they‚Äôre concerned with an even broader idea than that of the written word, well organized and published. The 50 Year Argument, then, suggests something important about cultural literacy and its intricate, necessary relationship with public engagement. This is the intersection where New York Review of Books has always thrived, and it‚Äôs territory in which they are increasingly alone.

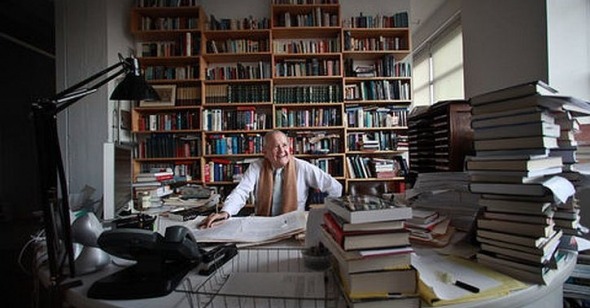

Silvers, bald and distinguished, and always seen in a suit and snappy tie, makes a great documentary subject‚ÄĒhe‚Äôs jovial and open, and his own cultural literacy and engagement is above reproach. An early scene of him in a cab captures him dictating an email about the situation in Iraq off-the-cuff to an assistant in the office, and you‚Äôll wish you could speak so well without rehearsal. The film isn‚Äôt required to offer a critical portrait of Silvers in any way, of course, but the portrayal sometimes approaches the hagiographic. There‚Äôs also the odd moment of tone-deafness: jumping from the early scene in Zuccotti Park to a swank cocktail reception celebrating the magazine‚Äôs fifty-year anniversary happens unironically despite revealing the disparity between the unwashed 99% and the well-paid literati giving voice to them. On the whole the film misses some of the verve and aesthetic boldness of Scorsese‚Äôs other documentaries‚ÄĒyou‚Äôll wish for those moments of oddity and fresh air sprinkled throughout Italianamerican, American Boy, and The Last Waltz to break up the interviews, archival footage, and lovely Brigitte Lacombe black-and-white photographs of the featured authors. Even though the film is largely anodyne in its presentation, its case for the continuing validity of a project like New York Review of Books is intellectually sound, more widely ranging than one would have any reason to expect, and politically engaged without being didactic. Not unlike its subject.