Back from the Dead

By Michael Koresky

The Mother of Tears

Dir. Dario Argento, Italy, Dimension

When Dario Argento’s now enshrined horror classics Suspiria and Inferno are fondly recalled, it’s never in terms of their narratives, characters, or even forward momentum. Rather, it’s the isolated images and set pieces: dark rooms drenched in red or blue gels, horrific deaths choreographed with the obsessive-compulsive precision of a ruthless artisan, gorgeous framing and pummeling soundtracks that heighten all the senses at once. Of course, then there are the idiotic plots: for while Argento illuminates the occult as a tactile, living thing, he has never shown the slightest interest in making that terror seem like something that could exist outside of the frame. It’s what separates even his best films (Deep Red, Suspiria, Opera) from seminal genre classics like Rosemary’s Baby, or the great early films from John Carpenter, which gave off the sense that evil is verifiably here on Earth as opposed to something to be beautifully set designed. Take away Argento’s undeniable craft, and what would you really be left with?

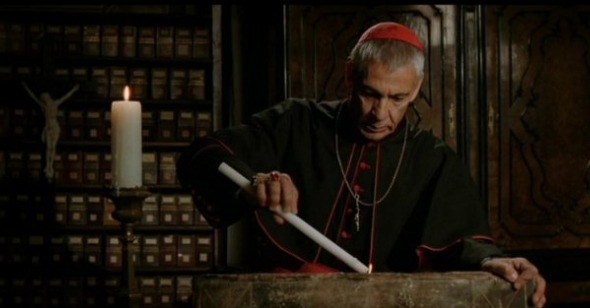

The answer is The Mother of Tears, the official third part of the “Three Mothers Trilogy,” that, while continuing the saga set forth by Suspiria and Inferno over thirty years ago, contains little of those films’ visual ingenuity, and a surplus of their unchecked sadism. Having the dubious distinction of being at once sickening and utterly ineffectual, Mother of Tears seems destined for a short burst of horror geek enthusiasm, soon to be tempered by the reality of its filmmaker’s sad decline. The basic Argento elements are in place (a book-smart female historian gets in over her head with the occult and searches for answers through musty, cobwebbed tomes and cavernous abandoned hallways) and the facts of the case are no more ridiculous than those in any of the Italian director’s other pieces of claptrap (construction workers at a cemetery in Rome unearth an ancient coffin and urn, which when opened unleashes, like, unimaginable horrors or something), but with its oppressively even lighting, lazy camera set-ups, and spatially unattractive compositions, there’s just not much here to look at.

Surely, the cheap production values of Mother of Tears will be recouped by some for their charming bargain-basement “aesthetic,” but Argento offers nothing visually transcendent enough to raise it above its obvious shock sound cuts and occasional reliance on primitive digital effects. Naturally, we get a parade of gory kills, although considering their de facto elaborate grotesqueness the question begs to be asked: is Argento envisioning truly “creative deaths” (a clichéd term in horror appreciation if there ever was one), or is he just finding different places to stab a female body? Surely to be much related to friends over drinks, the opening murder has a monkey-led army of cloaked evildoers forcing a metal jawbreaker into a woman’s gaping mouth until her lips split apart, before slicing open her belly and proceeding to strangle her with her own intestines. Effectively Grand Guignol, for sure, but by the time Argento sees fit to punish a lesbian couple with puncture wounds to the breasts and a large phallic iron rod between the legs, one needs to stop overlooking the filmmaker’s misogyny in favor of some sort of misguided auteurist defense.

Mother of Tears’ greatest asset, Argento’s festival-circuit darling daughter Asia, cast here as restoration student Sarah Mandy, is thus also its queasiest element. With her pouty, protruding lower lip, dark-circled eyes, and smoky purr, Asia is as compelling as ever, even when knowingly spouting inane dialogue; but when her dad’s camera caresses her naked body in a gratuitous shower scene, she simply becomes another in a cast brimming with violated women. With their supple breasts and crimson lipstick, the villains in this “second age of witches” look like little more than Red Shoe Diaries femmes fatales, prone to stripping off their clothes in sweltering dungeons when they’re not gallivanting around town garishly made-up as if en route to a Go-Go’s reunion show. Argento’s film is so feeble (check out a hilariously composed shot in which a frantic Asia panics on a payphone, while in the far background, to represent “all hell breaking loose on the streets of Rome,” two men in a parking lot push each other around like tantrum-throwing kindergarteners) that it mostly relies on the usual procession of occult library images (Hans Balding Gruen! Goya!) to do the heavy lifting, all set to a score that sounds like outtakes from The Omen (Ave Satani!). While it’s arguable whether Argento was ever “vital” in the first place, Mother of Tears shows fewer signs of life than ever. During its final, badly composited digital shot, when Asia laughs maniacally, she won’t be the only one.