Gathering Moss

by Elbert Ventura

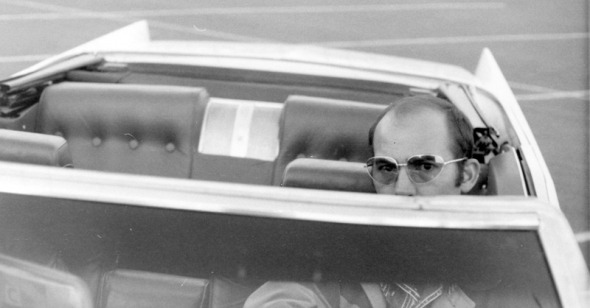

Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson

Dir. Alex Gibney, U.S., Magnolia Pictures

Hunter S. Thompson’s prose was nervy and pugnacious, his judgments bullying and hyperbolic, his life as volatile as any in postwar American letters. Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson couldn’t be any more different in mien and spirit. A couple of passages aside, it is almost perversely straightforward in light of its unstable subject, a chronological march through the heavy ’60s, the downer ’70s and the post-Reagan blur with a dutiful assemblage of talking heads and archival footage. The historical and cultural insights are all textbook, the music choices Forrest Gump–esque (if I hear Jefferson Airplane playing over images of Summer of Love San Francisco one more time…). What saves the movie is the man himself.

As a documentary subject, Hunter S. Thompson is can’t-miss, partly because he cultivated his persona for maximum shock and awe. Alex Gibney’s film evinces palpable affection for the man and gives his words and visage plenty of screen time. The roster of interviewees is impressive: in addition to Thompson’s two wives and only son, Tom Wolfe, George McGovern, Jimmy Carter, Pat Buchanan (!), Jimmy Buffett (!!), and Jann Wenner, among other luminaries, pay tribute to the self-styled creator of “gonzo journalism.” Lest that motley cast suggest otherwise, the talking-head choices are actually apt (Thompson admired Buchanan as a writer; he was good friends with Buffett), as each brings a shard of truth from divergent perspectives.

Spending its first half on Thompson’s rise that peaked with Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971), the movie relies on the same collection of tropes that have been exhausted by the commodification of boomer nostalgia. Even more difficult is the task that every film biographer confronts: condensing a life into a manageable running time. The movie is at its best when it bores into Thompson’s work. A chapter on Thompson’s classic Hell’s Angels: The Strange Tale and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs (1966), the book that launched his career, offers revelatory footage of pre-stardom Thompson; the sequence on his piece on the Kentucky Derby (1970), retrospectively seen as ground zero for gonzo, throbs with the borrowed urgency of his words (not to mention the febrile ghoulishness of Ralph Steadman’s cartoons). Contained in a staid frame, Thompson and his writings give the movie badly needed pop.

Though not exactly hagiographic, Gonzo borders on blindly worshipful. Sure, the talent was indisputable, but was there not a sliver of posturing there? And what about gonzo journalism’s influence? Friends reminisce about how Thompson helped destroy Edmund Muskie’s 1972 campaign by placing a scurrilous item in a story about the Democratic primary candidate’s addiction to a drug called Ibogaine. Thompson himself admitted that he “made up the rumor,” but everyone just laughed it off—that’s gonzo for you! The iconoclasm and rejection of Beltway clubbiness were badly needed, the foregrounding of the author less so, but in the era of the TV shoutfest and degraded “New Journalism,” reportorial accuracy and authorial effacement seem less passé than it must have seemed to Thompson and his peers.

Part of what makes Gonzo dull and superficial is the familiarity of its arcs: the rise and slow decline of the rock star, the efflorescence and gradual dimming of the counterculture’s hopes. The movie casts a sad-eyed glance at the autumnal Thompson, whose mythos became a ball and chain that grew heavier with each passing year. Once a perfect encapsulation of personal mood and national zeitgeist, “fear and loathing” (a phrase he first wrote after JFK’s assassination) became a tagline. Blandly celebratory and safely contained, Gonzo ends up as a by-the-numbers tribute and just another advertisement for the Sixties generation, adopting a reverential tone that Thompson, in his prime, would have cared little for. In the spirit of the good doctor, forget the facts and go for the fiction—rent Terry Gilliam’s lysergic Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998) instead, a movie (and a performance by Johnny Depp) that both depicted and embodied gonzo with unhinged brio.