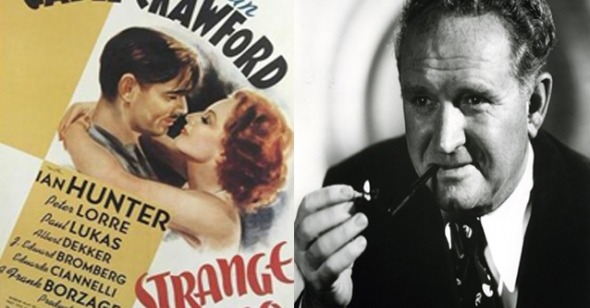

Frank Borzage: Hollywood Romantic, Week Six

Strange Cargo & Till We Meet Again

As the sixth and final week of Museum of the Moving Image's well-stocked overview of Frank Borzage's career arrives, it's worth taking a look back to survey the terrain that's been covered so far. Any gluttonous movie-watcher will be familiar with the muddled memories that come with consuming so much celluloid in just a few sittings—though MOMI, with its well-spaced weekend-only showings, allows more recovery time than most. Even still, after a retrospective like this an entire body of work is conflated into a confusion of scenes, images, dialogues, camera gestures, cut-aways, impressions.

The Borzage cult, which seems destined to remain a small and ever-shriveling sect, has enjoyed the privilege of seeing the director’s work reincarnated decade-by-decade during the course of these few weeks. There have been samples of the vocational years—an odd-duck Western like 1918's The Gun Woman, pitting a transplanted Boston Brahmin against native varmints, hinting at the palpitating ardor of films to come; the mounting promise of the mid-Twenties—the mawkish moving-on-up of 1925's Humoresque, with a handful of tenement images that might've come from Jacob Riis’s photoplates, or the admirably limpid rural melancholia of Lazybones, which basks in the other noble American archetype (“I loaf and invite my soul"); the fervently emotional features of Borzage's fecund late-Twenties output at Fox—films much admired by the Surrealists, with a singularly chaste, almost ethereal vision of life on the skids. And on through the Thirties, through prestige adaptation and collaboration with the leading literary lights of Scribner's literary crop from the decade past (Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms and the Fitzgerald-scripted Three Comrades), and prewar tracts whose pleas for a humane resolution to the Problems of Our Time are every bit as invested as Renoir's Front Populaire rally, The Crime of Monsieur Lange—no small feat in still-isolationist America.

The Borzage of the Forties, on display this weekend, is my least favorite of the bunch. Though the director never seems to have lost his fascination with the delicate struggle that's necessary to accomplish love—with people, yes, but more importantly with a person—there is increasingly an undercurrent of literal-minded, Presbyterian-dull religiosity that feels as cozy as a light Sunday nap in the pews, especially when placed side-by-side with the lavish rapture of the earlier works. 1940’s Strange Cargo, with Joan Crawford and Clark Gable, is as bad a film as Borzage ever made; a rakish prisoner's escape from Devil's Island is hobbled not only by a flat-footed handling of the on-the-lam sequences (our director is temperamentally unsuited to outdoor action), but a wedged-in religious allegory that might've been scripted by Jack Chick, escalating into the bathetic, thunderously stupid hysteria of a symbolic crucifixion on storm-tossed seas. It's spiritual kitsch rendered semi-respectable with a patina of age, but certainly not to be trusted as art—anyone who calls it that has made their definition of the word hopelessly baggy.

I care little more for 1944's Till We Meet Again, playing this weekend. Ray Milland, playing his usual upright, discreetly Welsh American, is a U.S. paratrooper shot down behind enemy lines, squired across Nazi-occupied France by nun-on-the-run Barbara Britton. The pleasant fiction of a united front of French resistance, organized through the Catholic church, is generously indulged here—the only visible Vichy stooge, in a countryside crawling with SS reserves, is Walter Slezak’s skittish, bowler-fondling mayor (this film's sin is by no means unusual—whitewashing our allies into opacity was a favorite pastime of wartime Hollywood—see the soft-focus Stalinism of Red Star or Mission to Moscow). It's not an egregiously bad film, but something milquetoast lurks under its concessions to German brutality—it's the war of banality versus evil. And, after all, the Summertime is so short...

That Borzage's body of work, when seen as a piece, amounts to something less than a pure stream of unfumbled mastery should come as no surprise to anyone who has fantasized filmographies based on a few publicity stills and the irresistible allure of unavailability, only to run aground on the dodginess of truth. The plain facts: lives spent in the movies, like most lives, rarely end on a high note (though Borzage did have one more masterpiece in him, 1948's Moonrise); we may celebrate the director's near-disappearance in the Fifties, for it is easy to imagine Borzage, so awed by the structural integrity of the loving family unit, overindulging the postwar victory lap of domestic propaganda that has become the shorthand definition of that era in the popular imagination.

But as this sighting comes to an end, as Frank Borzage returns to the fog of semi-legend, only to be spotted, reduced, on late-night TCM, we'd do well not to forget what's most important in his cinema: this is a man who photographed the landscape of the human face in close-up with an unparalleled patience, empathy, scrutiny, sensitivity. I’m put in mind of something R.W. Fassbinder said, regarding another master of the melodramatic form, Douglas Sirk, whose rise in Hollywood was roughly concurrent to Borzage's decline—“ made the tenderest films I know, they are the films of someone who loves people and doesn't despise them as we do.” It's a compliment that ultimately applies more to Borzage than to Sirk, for he seemed to exalt like few others in his characters’ joys. “Happiness writes white,” goes the old adage, but for Borzage, it's luminous. —NICK PINKERTON