All Together Now

by Genevieve Yue

Le Havre

Dir. Aki Kaurismäki, Finland/France, Janus Films

Aki Kaurismäki’s Le Havre starts like a caper film: two shoe-shiners stand at a railway station, waves of sneakers passing by. Then, a fine pair of leather oxfords stops before them. The camera tilts up to a man handcuffed to a briefcase, and, with his eyes darting around suspiciously, he lifts his shoe for a polish. He rushes off, and moments later we hear a gunshot. The churlish Marcel Marx (André Wilms) shrugs, “Well, at least I got paid first.”

True to Kaurismäki’s understated style, the setup runs into the blunt end of a deadpan joke; for nearly thirty years, his films have been less concerned with extraordinary events than the downtrodden people who impassively observe them. Quick to avoid the approaching police, Marcel closes up shop and ambles home, brushing off the incident as he does his grocer’s complaints of unpaid bills. Marcel stops in to greet his Finnish wife, Arletty (played by longtime Kaurismäki regular Kati Outinen), who feeds him and demurely sends him off with a few coins to the local dive. “Foreigners see bums in a more romantic light,” mutters Yvette, the bar owner, regarding Marcel, but if the neighbors disapprove of this one-time Parisian bohemian, Marcel doesn’t seem to care. Here in the port city of Le Havre, in a dingy quarter left untouched after the war and the rest of the modernizing world, they’ve long put up with each other in grumbling complacence.

The frozen time of this “unrealistic film,” as Kaurismäki calls it, is punctuated by more than a few glimpses of the contemporary world. A television news program reporting on a refugee camp in Calais interrupts the typically restrained mise-en-scène, and when a boy goes missing from a container filled with Gabonese exiles that has arrived at the docks, a newspaper headline speculates that he is connected to Al-Qaeda. These markers, however, are no less precise than the spare objects that describe the offbeat world of Le Havre—Arletty’s two frocks hanging in her closet, a rotary phone, a pineapple carried into a bar. Together they illustrate the delicate balance between fairy-tale optimism and hard-knock cynicism, between timelessness and timeliness. And Kaurismäki’s sly comedic wit, instead of softening the contrast, sharpens it. His brand of humor, which has earned him cult as well as critical admiration, could be compared to the spectacle of a deflating balloon, a stark observation of the small, absurd, and drawn-out tragedies of ordinary life.

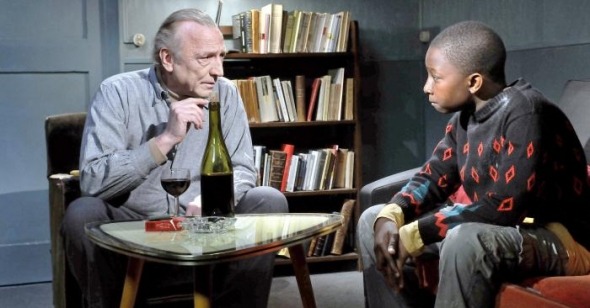

Though the arrival of the young refugee Idrissa (Blondin Miguel) shapes the film’s narrative, the story belongs to Marcel, who, after surreptitiously leaving a sandwich for the boy, finds him asleep in his shed. Without any hesitation, Marcel sets upon the task of reuniting Idrissa with his mother in London, and the rest of the town, save a shadowy informant (Jean-Pierre Léaud), rally to the cause with a vigor reminiscent of Resistance-era France. As Marcel feeds Idrissa and teaches him the humble manner of his trade—it’s difficult work, he explains, but it’s “closest to people”—the previously dismissive neighbors suddenly praise and protect him from the nosy Inspector Monet (Jean-Pierre Darroussin), who aims to deport the boy. In the film’s most fanciful sequence, Marcel throws a “trendy benefit concert” to pay for Idrissa’s passage. Little Bob, Le Havre’s homegrown answer to Bruce Springsteen, takes the stage, and Kaurismäki, no stranger to lengthy musical interludes, lets their song play out. True to their name, their diminutive lead, Roberto Piazza, rocks out in white pompadour and red motorcycle jacket.

Arletty, meanwhile, falls ill with a terminal disease, but she convinces the doctor to hide the seriousness of her condition from Marcel. When the doctor suggests offhand that miracles sometimes happen, Arletty is doubtful. “Not in my neighborhood,” she says. Outinen here appears simultaneously young and old, both the naïve blossom like those on her yellow dress and the wizened woman who knows well the tenderness under her husband’s rough exterior. Whether her fate comes as a surprise will depend on the viewer’s investment in Kaurismäki’s view of Le Havre’s working-class hardships. The film’s vintage veneer contributes significantly to this outlook, yet while it borrows liberally from classic French auteurs ranging from Bresson to Tati, its core is unmistakably, cheerfully, and bitterly Kaurismäki’s: however bleak circumstances may appear, Le Havre insists on the need for people to work their problems out together, or at least share them over a drink.

Kaurismäki’s humanism is clear even beyond matters of plot—when, for example, the police open the cargo hold of “still lives,” as one of the officer calls them, the camera lingers on the individual faces of the Gabonese passengers, giving each of them, absent their own storylines, an undeniable presence. While taciturn characters are nothing new to Kaurismäki films, these mute stares are different, suggesting the possibility of matters left unsaid and lives overlooked. Later, in a similar instance, Idrissa stands motionless before a record player, from which we hear Blind Willie McTell’s “Statesboro Blues.” In his stillness, the song feels immense, and we can only imagine what this mostly quiet boy, after a long, dangerous trip across the sea, is thinking. As McTell mournfully sings, what begins as a man’s banal plea for his lover to let him in becomes a list of accumulated indignities suffered not only by him but also his entire family, and, in the last lines, the whole city of Statesboro. In this song and in this film, everyone awakes to their shared plight, suddenly apparent, suddenly visible, to themselves and to everyone else.